The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

But lets the greater felon loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

(Anonymous protest poem from the 17th century)

In 1762 Jean Jacques Rousseau published his book, The Social Contract, in which he wrote,

"In Greece, all that the populace had to do, it did for itself; it was

constantly assembled in the public square." Rousseau was well aware of

the importance of public spaces when it came to political change.

Indeed, the storming of the Bastille

on 14 July 1789 showed the power of the populace against armed guards

defending the medieval fortress, armory, and political prison in Paris

which at the time represented royal authority. Interestingly enough, the

decision had also been taken to replace the Bastille with an open

public space and the fortress was demolished within five months. Since

then many open public spaces around the world have been the centres of

political activity. Political art became an important part of these

demonstrations and uprisings in the form of murals, political graffiti

and carnival floats. Even earlier political art in the poetic form had a

role to play in Rome in the 16th century as people posted poems

critical of the popes on statues (originating with the Il Pasquino

statue) which soon became known as the Talking Statues of Rome.

I choose to reflect the times and the situations in which I find myself. How can you be an artist and not reflect the times?

(Nina Simone)

I choose to reflect the times and the situations in which I find myself. How can you be an artist and not reflect the times?

(Nina Simone)

History Goes to the Wall

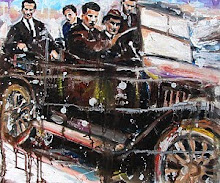

In the 1930s the Mexican mural movement brought a whole new way of seeing murals and political art to the disaffected public. Artists such as Diego Rivera, José Orozco and David Siqueiros created murals which not only depicted Mexican society but also incorporated imagery showing the history of Mexico going back to Aztec culture. These murals depicted the revolutionary struggles of Mexico's peasant farmers and working classes on the land and in the factories. Large murals allowed Rivera to bring his imagery of peasants and working people out of the gallery and into the public space where those depicted would be able to see them. The large 'canvasses' of walls also allowed him to create painted works into which he could put depictions of large groups of people, factories, battle scenes, industrial and scientific imagery accompanied with mythical symbolism and images from nature. His artwork changed from a painterly to a more graphic style to allow for this huge increase in subjects and range of subject matter.

In the 1930s the Mexican mural movement brought a whole new way of seeing murals and political art to the disaffected public. Artists such as Diego Rivera, José Orozco and David Siqueiros created murals which not only depicted Mexican society but also incorporated imagery showing the history of Mexico going back to Aztec culture. These murals depicted the revolutionary struggles of Mexico's peasant farmers and working classes on the land and in the factories. Large murals allowed Rivera to bring his imagery of peasants and working people out of the gallery and into the public space where those depicted would be able to see them. The large 'canvasses' of walls also allowed him to create painted works into which he could put depictions of large groups of people, factories, battle scenes, industrial and scientific imagery accompanied with mythical symbolism and images from nature. His artwork changed from a painterly to a more graphic style to allow for this huge increase in subjects and range of subject matter.

Military Paint the Town Red

The

depiction of historical figures and current political struggles became

synonymous with the political struggles in Northern Ireland as both

sides used murals

to heighten and strengthen their views on the future of Ireland. The

Irish Republican areas were decorated with murals of the local hunger

striker Bobby Sands but also murals in solidarity with international

revolutionary groups thus making it a truly global art form rather than

just a local focus. In some cases the murals themselves became a site of

resistance as British soldiers threw paint bombs at them which in turn

led to the creation of designs which could be easily repainted.

Liberalism,

austere in political trifles, has learned ever more artfully to unite a

constant protest against the government with a constant submission to

it.

(Alexander Herzen)

While murals on local infrastructure belonging to the people were generally the case in Northern Ireland, murals on the Berlin Wall and now the walls in the West Bank are a type of 'arttack' on the presence of the wall itself. Like the Talking Statues of Rome, the Berlin wall became a place where people could express their opinions while tourists traveled to see the artwork. Unfortunately this prettifying aspect of the art may backfire as one writer noted that when Banksy "painted large murals onto the Bethlehem walls, a Palestinian onlooker told him that he made the wall look beautiful. Banksy thanked him only to be told, “We don’t want it to be beautiful. We hate this wall. Go home.”" However, connections between the West Bank walls and the Berlin wall can be seen in the visual similarity between the mural of Leonid Brezhnev and Erich Honecker in a fraternal embrace (entitled "My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love ") and the recent mural of Trump and Netanyahu sharing a kiss in a West Bank wall mural. In both cases symbolic depictions of these politicians show up real and problematic aspects of contemporary symbiotic political relationships especially for the people who have to endure the hardships of separation caused by the existence of the walls. The presence of the murals on the walls keeps to the fore, like a nagging toothache, the issues raised in a more efficient way than, for example, constant leafleting might do.

(Alexander Herzen)

While murals on local infrastructure belonging to the people were generally the case in Northern Ireland, murals on the Berlin Wall and now the walls in the West Bank are a type of 'arttack' on the presence of the wall itself. Like the Talking Statues of Rome, the Berlin wall became a place where people could express their opinions while tourists traveled to see the artwork. Unfortunately this prettifying aspect of the art may backfire as one writer noted that when Banksy "painted large murals onto the Bethlehem walls, a Palestinian onlooker told him that he made the wall look beautiful. Banksy thanked him only to be told, “We don’t want it to be beautiful. We hate this wall. Go home.”" However, connections between the West Bank walls and the Berlin wall can be seen in the visual similarity between the mural of Leonid Brezhnev and Erich Honecker in a fraternal embrace (entitled "My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love ") and the recent mural of Trump and Netanyahu sharing a kiss in a West Bank wall mural. In both cases symbolic depictions of these politicians show up real and problematic aspects of contemporary symbiotic political relationships especially for the people who have to endure the hardships of separation caused by the existence of the walls. The presence of the murals on the walls keeps to the fore, like a nagging toothache, the issues raised in a more efficient way than, for example, constant leafleting might do.

Graffiti Grows Up

Unlike murals, graffiti implies text rather than image and in modern times has become known as tagging, which at its most basic is a personalised signature. As an art form it has moved on in leaps and bounds as we have seen in a move from form to content. Political graffiti is now a form of mural on the go as extremely difficult and dangerous times politically do not allow for leisurely mural painting. It can also give rise to a type of Expressionist mural as faster mark-making and very simplified designs become necessary. A striking example is of a simple but effective drawing of Egyptian police beating and stripping a veiled female protester in Tahrir Square, Cairo, based on a circulated photo during the Arab Spring. As one writer declared:

"Indeed, in the past few weeks Tahrir has became a truly public square. Before it was merely a big and busy traffic circle—and again, its limitations were the result of political design, of policies that not only discouraged but also prohibited public assembly. Under emergency law—established from the moment Mubarak took office in 1981 and yet to be lifted—a gathering of even a few adults in a public square would constitute cause for arrest. Like all autocracies, the Mubarak government understood the power of a true public square, of a place where citizens meet, mingle, promenade, gather, protest, perform and share ideas."

Unlike murals, graffiti implies text rather than image and in modern times has become known as tagging, which at its most basic is a personalised signature. As an art form it has moved on in leaps and bounds as we have seen in a move from form to content. Political graffiti is now a form of mural on the go as extremely difficult and dangerous times politically do not allow for leisurely mural painting. It can also give rise to a type of Expressionist mural as faster mark-making and very simplified designs become necessary. A striking example is of a simple but effective drawing of Egyptian police beating and stripping a veiled female protester in Tahrir Square, Cairo, based on a circulated photo during the Arab Spring. As one writer declared:

"Indeed, in the past few weeks Tahrir has became a truly public square. Before it was merely a big and busy traffic circle—and again, its limitations were the result of political design, of policies that not only discouraged but also prohibited public assembly. Under emergency law—established from the moment Mubarak took office in 1981 and yet to be lifted—a gathering of even a few adults in a public square would constitute cause for arrest. Like all autocracies, the Mubarak government understood the power of a true public square, of a place where citizens meet, mingle, promenade, gather, protest, perform and share ideas."

Mural of Egyptian police beating and stripping a veiled female protester

When

it comes to war, we focus more on the mainstream coverage of the event,

rather than the event itself. People dying is never funny. Protest

puppets are always funny.

(Mo Rocca)

(Mo Rocca)

Floating Your Boat

However, the most articulated form of political art of recent times is the papier-mâché floats of the German carnival, Rosenmontag, or Rose Monday, on the streets of Cologne and Düsseldorf. Political satire is the main theme of the floats and no politician is sacrosanct. The papier-mâché sculptures show politicians and political symbols in various compromising positions, e.g. Donald Trump humping the Statue of Liberty. They are political cartoons reified and yet a form of political satire on the go as floats are paraded through the streets for carnival (like a modern Saturnalia) that would never be allowed by the state as an official or permanent type of sculpture in a public space.

However, the most articulated form of political art of recent times is the papier-mâché floats of the German carnival, Rosenmontag, or Rose Monday, on the streets of Cologne and Düsseldorf. Political satire is the main theme of the floats and no politician is sacrosanct. The papier-mâché sculptures show politicians and political symbols in various compromising positions, e.g. Donald Trump humping the Statue of Liberty. They are political cartoons reified and yet a form of political satire on the go as floats are paraded through the streets for carnival (like a modern Saturnalia) that would never be allowed by the state as an official or permanent type of sculpture in a public space.

Rose Monday carnival papier-mâché floats

The political machine triumphs because it is a united minority acting against a divided majority.

(Will Durant)

The difficulty for modern public resistance is the rationalisation of the public space with CCTV, satellite mapping and photography and militarisation of police forces. Like the 18th century inclosure of the commons acts, modern governments seem determined to limit access to the public space by licensing, movement restrictions and police intimidation of demonstrators. The use of the public space in recent colour revolutions shows how certain elements combine social media and public space activism to bring about Western political agendas, sometimes successfully, sometimes not. The existence of snipers in critical public situations has also caused fear and panic that could easily create a potential reticence to use the public space as a form of political resistance.

Moreover, it could be argued that the virtual public space has replaced the actual public space with social media. Yet it can be seen the internet is gradually being censored in different ways by governments around the world. The future of political campaigning on the web is uncertain. However it is interesting to see another art form, performance (e.g. the 'die-in'), being used by demonstrators dedicated to people who have been killed by police in the USA in recent years. Performance, like political graffiti and carnival floats, is art that can inhabit or be created in the public space quickly, thus reducing reaction from the state. It also shows that protest or activist art can involve everyone, not just professional artists and designers. Posters and hand-held signs also allow demonstrators to intensify their participation in activities in the public space. Music and ballads often play an important role in demonstrations - particularly ballads - as often an event is converted into a ballad faster than any other art form.

Here we shall stay

sing our songs

take to the angry streets

fill prisons with dignity

(Tawfik Ziad)

Art in the public space has always been contested. In Ireland, many colonial sculptures were either removed or blown up (e.g. Nelson's Pillar) to be replaced with nationalist sculptures instead. Murals are often painted over by state officials. Political posters are taken down or removed not long after they are put up. Performance protesters are removed by police. However, art in all its forms has a role in uniting and giving meaning to struggles the world over. Gathering in the public space is still the most effective and direct form of collective resistance despite state paraphernalia (riot police, water cannons etc.). If, at some time in the future those struggles are successful through the combined activities of a risen people, then the necessity for resistance art will wither away.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country at http://gaelart.blogspot.ie/