Traditions of the Winter Solstice

Christmas is an ancient feast that has many positive associations for people

around the world. While the bible places the birth of Christ in Bethlehem it

does not say when, but by the 4th century the Churches in the East were

celebrating it on January 6 and the Churches of the West on December 25.

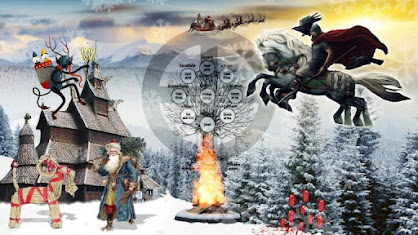

One thing is certain about Christmas is that it is rooted in many traditions and superstitions relating to nature that existed long before Christmas and many have continued in one form or another to the present day. The many strands of Christmas can be seen in the variety of different traditions associated with, or originating in, places all over Europe. These strands are, inter alia, the solstice, the Nativity, Saturnalia, Yuletide, St Nicholas, Father Christmas, and Grandfather Frost (Ded Moroz).

The association of Christmas with its earlier midwinter nature worship traditions declined as the Church exerted its power and authority over pagan practices and in more recent centuries as the industrial revolution took people away from the land and into the cities and factories. Since then industrialisation has taken over many aspects of people’s lives as they shifted from being producers to consumers.

One thing is certain about Christmas is that it is rooted in many traditions and superstitions relating to nature that existed long before Christmas and many have continued in one form or another to the present day. The many strands of Christmas can be seen in the variety of different traditions associated with, or originating in, places all over Europe. These strands are, inter alia, the solstice, the Nativity, Saturnalia, Yuletide, St Nicholas, Father Christmas, and Grandfather Frost (Ded Moroz).

The association of Christmas with its earlier midwinter nature worship traditions declined as the Church exerted its power and authority over pagan practices and in more recent centuries as the industrial revolution took people away from the land and into the cities and factories. Since then industrialisation has taken over many aspects of people’s lives as they shifted from being producers to consumers.

As direct contact with nature declined and scientific knowledge was applied to production, our lives were made easier by an abundance of relatively cheap goods and food. These benefits have come at another price though as industrialisation and technology the world over pushes nature further and further into ecological crises. There is much discussion and debate about the potential for a tipping point as the destruction of ecosystems and climate change move headlong towards irreversible damage of the Earth's biosphere.

This has come about, partly due to our alienation from nature, but also due to a system which blinds us to the excesses of production through mass media, and Christmas has become the vehicle for the worst excesses of industrialisation, commercialisation and commodification. However, this is a gross distortion of its roots in respecting nature and nature worship which was ultimately about a heightened awareness of survival in an unpredictable world.

Sex

The predominant figure of Christmas has become Santa Claus (Dutch: Sinter Klaas) and originated in the stories around St Nicholas, the 4th century Bishop of Myra (Turkey), giving anonymous gifts to help people in need or trouble.[1] In many European regions St Nicholas came door to door with a bishop's mitre and crosier on his feast day, December 6. He was accompanied by his helper Ruprecht or Krampus as he is known in the Alpine regions. Krampus is depicted as half goat and half demon and punished misbehaving children with a rod.

It is believed that Krampus derives from the much earlier pre-Christian Norse mythology and that he was the son of the god of the underworld Hel. While the name Krampus is believed to originate from Krampen meaning 'claw', Ruprecht is believed to be from “Hruodperaht” meaning “gloriously shining one” another name of Wotan. Their negative status is likely the result of Christian attempts assert dominance over the pagan peoples of the time, in the same way that the Celtic goddess Bridget was demoted by the Christian church to St Bridget. Krampus is an evil fertility demon who scares children (reversing his earlier role as fertility god) with his hazel wood rod:

"The

hazelnut was holy to Donar, the God of marital and animal fertility. The hazel

wood rod was considered a great rod of life. With this symbol of the penis,

women and animals were beaten "with gusto" in order for them to

become fertile." [2]

This fertility rite has continued to the present day on Easter Mondays in the Czech Republic when young women are whipped with a braided rod of willow called a pomlázka to "assure womankind with good health, fresh look and keep fertility. The girls then give coloured or painted eggs to boys and men as a sign of their thanks and forgiveness."

During the 12th century the church tried to end the Krampus celebrations but it seems that, like with many popular traditions, they re-surfaced and were re-integrated back into church traditions. Unlike the 'demonised' Krampus, the Christian St Nicholas distributed typical gifts of nuts, dried fruits, chocolate, spices and toys.[3] These gifts were also symbols of fertility. Hazelnuts helped people survive winter as they could be easily stored and were rich in fats and vitamins. Apples were associated with the Tree of Paradise and dried fruits such as oranges and lemons served as fertility symbols in the Mediterranean countries as they were the first fruit of the year and thus herald a good harvest.[4]

Drugs

Another major association of Norse mythology with Christmas is the reindeer pulling the Santa's sleigh. The first mention of St Nicholas in the air in popular mythology is of him "riding jollily among the tree-tops, or over the roofs of the houses, now and then drawing forth magnificent presents from his breeches pockets and dropping them down the chimneys of his favourites" is by Washington Irving in his satirical work, A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker (1809). At this point St Nicholas was not associated with Christmas and presents were exchanged on the night before his feast day on December 6.

However, in a poem written in 1822, Clement Moore has St Nicholas arrive with his presents on the night before Christmas and in "a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny reindeer" who "would mount to the sky [...] with a sleigh full of toys" and then go down the chimneys to deliver his gifts thus shifting celebrations of St Nicholas in the United States from his feast day on December 6 to Christmas Eve on December 24 instead.[5]

The phenomenon of flying animals has long been associated in Norse mythology with Wotan and his flying eight legged horse Sleipnir, and with Thor and his flying goat-drawn chariot.

"Odin and Sleipnir" (1911) by John Bauer

Wotan is depicted as one-eyed and long-bearded in Old Norse texts and is a fierce god associated with wisdom, healing and war. Children would leave straw in their boots for Sleipnir by the hearth and Wotan would exchange it for a gift in return for their kindness. Thor was also depicted as a fierce god of thunder and lightning, storms, oak trees and fertility. Another god, Morozko, the powerful and cruel Slavic god of frost and ice could freeze people and landscapes at will, became known as Ded Moroz (Grandfather Frost) but was eventually demonised by the Russian Orthodox Church. As our fear of nature declined and Christmas became more of a child-centered celebration, the depictions of these gods became less fierce over time.

It seems that what shamanism and fertility rites have in common is the idea of directly engaging with nature to secure desired material or spiritual goals. Both Krampus and Shamanism have been associated with Satan who "uses deception and demonic spirits seeking our destruction" yet their popularity has ebbed and flowed over the centuries without disappearing altogether.

Rollickin' Roles

Similarly the Bacchanalian aspect of Christmas celebrations is a

survival of Saturnalia, the Roman celebration of Saturn the

"god of generation, dissolution, plenty, wealth, agriculture, periodic

renewal and liberation" which could also be described as an engagement

with the cycles of nature. Saturnalia was

"a time of feasting, role reversals, free speech, gift-giving and revelry"

held on December 17 of the Julian calendar and was subsequently extended to 23

December. Saturnalia originated as a farmer’s festival to mark the end of the

autumn planting season in honour of Saturn (satus means sowing).

According to Justinus, the 2nd century Roman historian, these celebratory aspects of Saturnalia derived from, and were explained by, its origins with pre-Roman peoples of Italy who:

"were the Aborigines, whose king, Saturnus, is said to have been a man of such extraordinary justice, that no one was a slave in his reign, or had any private property, but all things were common to all, and undivided, as one estate for the use of every one; in memory of which way of life, it has been ordered that at the Saturnalia slaves should everywhere sit down with their masters at the entertainments, the rank of all being made equal."

Once again the association with nature and the Golden Age (when people lived in

peace and harmony) forms the basis of a celebration which was to be co-opted by

the Church and eventually attacked for its excesses. According to a Puritan

minister in 17th century England, Increase Mather, Christmas occurred on

December 25 not because “Christ was born in that month, but because the

heathens’ Saturnalia was at that time kept in Rome, and they were willing to

have those pagan holidays metamorphosed into Christian [ones]. Stephen

Nissenbaum, in his book The Battle for

Christmas, writes:

“Puritans believed Christmas was basically just a pagan custom that the

Catholics took over without any biblical basis for it. The holiday had

everything to do with the time of year, the solstice and Saturnalia and nothing

to do with Christianity.”

Presumably the masters could not cope with the concept of equality and

saw Saturnalia instead as a role reversal. In pre-industrial England people

would elect a Lord of Misrule who would be in charge of Christmas festivities

and who even had license to poke fun at the nobility.[7]

Yet the Lords of Misrule were an important aspect of Christmas as the reversal

of traditional social norms was a safety valve for class tensions in England.

It was around this time that the personification of Christmas as Father

Christmas began to appear.

Father Christmas 1848

He was associated not with children, presents, chimneys or stockings, but with adult merrymaking and feasting. During Christmas 'great quantities of brawn, roast beef, 'plum-pottage', minced pies and special Christmas ale were consumed' and people enjoyed singing, dancing and card games resulting in 'drunkenness, promiscuity and other forms of excess.' Thus when the Puritans took over government in the 1640s they tried 'to abolish the Christian festival of Christmas and to outlaw the customs associated with it'. The satirical Royalist poet, John Taylor, wrote in The Complaint of Christmas:

"All the liberty and harmless sports, with the merry gambols, dances and friscals [by] which the toiling plowswain and labourer were wont to be recreated and their spirits and hopes revived for a whole twelve month are now extinct and put out of use in such a fashion as if they never had been. Thus are the merry lords of misrule suppressed by the mad lords of bad rule at Westminster."

However by the 1650s it was reported that the taverns were full on Christmas

day, churches were decorated in rosemary as usual, Christmas Boxes had been

given out, presents exchanged and mummers paid despite the bans. Worse still

violence broke out in London when:

"a large crowd of Londoners gathered to prevent the mayor and his

marshalls removing the Christmas decorations which some of the city porters had

draped around the conduit in Cornhill. The confrontation ended in uproar, with

arrests, injuries, and the bolting of the mayor's frightened horse."

The Christmas celebrations returned with Charles II in 1660 and showed

once again the attempt to impose a narrow religious view on the multifaceted

ancient traditions of people had failed.

Trees

Trees

Somewhat earlier, in the 14th and 15th centuries in Germany, craftsmen began to

decorate their guild halls with trees and adorning them with fruits and nuts.

This eventually led to the German, Charlotte, who married King George III in

1761, potting up and decorating a yew tree and initiating the custom in

England. Legend has it that in Germany, St Boniface, an historical figure from

the 7th century, saw a group of people honouring the sacred tree, Donar's Oak

(sometimes referred to as Thor's Oak) somewhere around Hesse, became angry and

chopped the tree down (and added insult to injury by using the wood to build

his church).

St Boniface chopping the oak tree

Sacred trees and sacred groves were very important to the Germanic peoples and were too important to be cut down. Again we can see that the earlier traditions of pre-Christian society revolved around revering nature:

"some were wont secretly, some openly to sacrifice to trees and springs; some in secret, others openly practiced inspections of victims and divinations, legerdemain and incantations; some turned their attention to auguries and auspices and various sacrificial rites; while others, with sounder minds, abandoned all the profanations of heathenism, and committed none of these things."

Over time, cutting the evergreen tree and bringing it indoors became an

important part of Christmas traditions [see my previous article on Christmas

trees] despite church proscription, because of its shamanic-pagan past.

Another early nature-based tradition is the wassail in England. Wassailing is a very ancient custom that is referenced in history as early as the eighth-century poem Beowulf. The word 'wassail' is believed to be derived from the Old Norse 'ves heil' and the Old English 'was hál' and meaning "be in good health" or "be fortunate." The wassail had an important significance for farmers:

Another early nature-based tradition is the wassail in England. Wassailing is a very ancient custom that is referenced in history as early as the eighth-century poem Beowulf. The word 'wassail' is believed to be derived from the Old Norse 'ves heil' and the Old English 'was hál' and meaning "be in good health" or "be fortunate." The wassail had an important significance for farmers:

"In parts of Medieval Britain, a different sort of wassailing emerged: farmers wassailed their crops and animals to encourage fertility. An observer recorded, "They go into the Ox-house to the oxen with the Wassell-bowle and drink to their health." The practice continued into the eighteenth century, when farmers in the west of Britain toasted the good health of apple trees to promote an abundant crop the next year. Some placed cider-soaked bread in the branches to ward off evil spirits. In other locales, villagers splashed the trees with cider while firing guns or beating pots and pans."

Wassailing the apple tree

The Apple Tree Wassail lyrics anticipate the next year and a good crop:

"(It's) Our wassail jolly wassail!

Joy come to our jolly wassail!

How well they may bloom, how well they may bear

So we may have apples and cider next year."

Solstice and the Unconquered Sun

Our awareness of mid winter and the solstice ('sun stands still') is shown to go back to the late Neolithic and Bronze Age with Newgrange in Ireland and Stonehenge in England. In both cases the monuments have been aligned to the solstice, sunrise at Newgrange and sunset at Stonehenge. It has been the occasion of celebrations, rituals and gatherings as the sun appears to be reborn and the days start getting longer again. After this time food became scarce (January to April) which were known as the 'famine months'. It was the last feast of the year as cattle were slaughtered and wine and beer were ready for drinking. The 'rebirth' of the sun was known as Sol Invictus or the ‘unconquered sun’ god during the Roman Empire in the 3rd century CE and the Emperor Aurelian dedicated a temple to Sol to be celebrated on December 25. Solar deities have been represented as both gods and goddesses in different cultures and are particularly important in mid winter when the sun is low in the sky. In many countries in Europe the tradition of the Yule log burning was an important festival to help strengthen the weakened sun.

Yule log

A large log, big enough to burn for the 12 days of

Christmas, was brought into the houses and burned. It was believed to have

originated with the Norse and the Celts who had large bonfires to welcome the

return of the sun. The log was thought to have magical properties and the ashes

were then used as fertiliser and as cures for both people and animals and would

protect them for the year to come.

Nature

Throughout the world there have been many forms of nature worship demonstrating that people respected and feared nature in equal amounts over the millennia. We have a complex relationship with nature, indeed we are an important part of nature. We have to negotiate every aspect of that relationship, be it food, water, reproduction, climate (storms avalanches, floods, droughts, fires), the seasons, the geophysical (earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes), light (length of day, sleeping during hours of darkness) etc.In the past people hoped and prayed that in the next year nature would allow them to live well again and consequently treated nature with respect. To do that people were careful not to over-exploit nature in various ways: by leaving land fallow, having food taboos, allowing areas to regenerate by moving on, by not over-using a food resource, thus creating the basis of sustainability into the future. Their respectful attitude to nature was reflected in what we call superstitions and paganism but it allowed them to celebrate Christmas without guilt in the knowledge that they had treated nature well and that nature would reciprocate with a bountiful harvest the next year.

Today, on the other hand, we are alienated from this way of thinking and living to the extent that people have lost direct control of their relationship with nature. The ever increasing industrial overproduction of meat, over-fishing, over-fertilisation, deforestation, air pollution and extractivism is pushing nature to extremes and already we are seeing the catastrophic results of this in climate change. Maybe as climate change brings ever fiercer storms and destruction of food production we will learn to respect and fear nature again.

Nature

Throughout the world there have been many forms of nature worship demonstrating that people respected and feared nature in equal amounts over the millennia. We have a complex relationship with nature, indeed we are an important part of nature. We have to negotiate every aspect of that relationship, be it food, water, reproduction, climate (storms avalanches, floods, droughts, fires), the seasons, the geophysical (earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes), light (length of day, sleeping during hours of darkness) etc.In the past people hoped and prayed that in the next year nature would allow them to live well again and consequently treated nature with respect. To do that people were careful not to over-exploit nature in various ways: by leaving land fallow, having food taboos, allowing areas to regenerate by moving on, by not over-using a food resource, thus creating the basis of sustainability into the future. Their respectful attitude to nature was reflected in what we call superstitions and paganism but it allowed them to celebrate Christmas without guilt in the knowledge that they had treated nature well and that nature would reciprocate with a bountiful harvest the next year.

Today, on the other hand, we are alienated from this way of thinking and living to the extent that people have lost direct control of their relationship with nature. The ever increasing industrial overproduction of meat, over-fishing, over-fertilisation, deforestation, air pollution and extractivism is pushing nature to extremes and already we are seeing the catastrophic results of this in climate change. Maybe as climate change brings ever fiercer storms and destruction of food production we will learn to respect and fear nature again.

Notes:

[1] Nicholas: The Epic Journey from Saint to Santa Claus, by Jeremy Seal, p28

[2] Pagan Christmas: the Plants, Spirits, and Rituals at the Origin of Yuletide, by Christian Ratsch and Claudia Muller-Ebeling, p33

[3] Pagan Christmas, p36[4] Pagan Christmas, p52/3

[5] From Stonehenge to Santa Claus: The Evolution of Christmas, by Paul Frodsham, p164

[6] Pagan Christmas, p46/47

[7] Celebrate the Solstice: Honoring the Earth's Seasonal Rhythms through Festival and Ceremony, Richard Heinberg, p107

[2] Pagan Christmas: the Plants, Spirits, and Rituals at the Origin of Yuletide, by Christian Ratsch and Claudia Muller-Ebeling, p33

[3] Pagan Christmas, p36[4] Pagan Christmas, p52/3

[5] From Stonehenge to Santa Claus: The Evolution of Christmas, by Paul Frodsham, p164

[6] Pagan Christmas, p46/47

[7] Celebrate the Solstice: Honoring the Earth's Seasonal Rhythms through Festival and Ceremony, Richard Heinberg, p107

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist,

lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on

contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of

Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along

with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the

world can be viewed country by country at http://gaelart.blogspot.ie/.