Mary Robinson, Inauguration speech as President of Ireland, December 3, 1990

"Dublin is connected with Irish patriotism only by the scaffold and the gallows. Statue and column do indeed rise there, but not to honour the sons of the soil. The public idols are foreign potentates and foreign heroes [...] the Irish people are doomed to see in every place the monument of their subjugation; before the senate house, the statue of their conqueror, within the walls tapestries with the defeats of their fathers. No public statue of an illustrious Irishman has ever graced the Irish Capital. No monument exists to which the gaze of the young Irish children can be directed, while their fathers tell them, 'This was to the glory of your countrymen'."

Dublin University Magazine (1856)

"Grey brick upon brick,

Declamatory bronze

On sombre pedestals –

O’Connell, Grattan, Moore –

And the brewery tugs and the swans

On the balustraded stream

And the bare bones of a fanlight

Over a hungry door

And the air soft on the cheek

And porter running from the taps

With a head of yellow cream

And Nelson on his pillar

Watching his world collapse."

Dublin by Louis MacNeice

Introduction

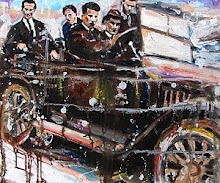

On the night of the 8 March 1966 a massive explosion was heard in the centre of Dublin and Nelson's Pillar came crashing to the ground in hundreds of tons of rubble. No one was hurt and a stump was all that could be seen of the 157 year old monument. It was not the first time that monuments had been attacked in Ireland and certainly not the last, at least figuratively, with a series of later monuments accruing many derogatory nicknames from the Dublin people.

The recent spate of attacks on monuments in the US and the Uk has opened up the debate on the cultural issues they provoke, ranging from those who can't believe the attacks hadn't happened sooner to those who see their destruction as mob vandalism.

Here, as everywhere, the public sphere is a highly contested one and not just culturally. For example, when the Irish Republic unilaterally declared independence in 1919, the Dáil Courts (Republican Courts) were set up, creating for the time being, a parallel (and popular) judicial system that frustrated the colonial power by undermining British rule in Ireland, and continued until independence.

Similarly the imposition of British cultural history in Ireland, through its monuments, was resented and these monuments became the focal point for the beginnings of a new public cultural space after independence. By wiping the slate clean, presumably it was thought, it would be possible to create a new progressive space based on Irish revolutionary figures. However, it did not quite work out like that. As in the political sphere, the public sphere remained a highly contested arena with successive conservative governments using different tactics to defer, reject or hinder progressive sculpture in Dublin.

I will look at the fate of some of these British historical monuments and the possibilities for future monuments that would more accurately reflect Irish peoples' historical struggles for freedom and independence.

'Removing' colonial history

(Photo by Mick Kenny)

(Photo by Mick Kenny)

William of Orange (1928)

In 1928 the statue of William of Orange (1701–1928) at College Green (in front of Trinity College) was damaged after an explosion on the anniversary of Armistice Day in 1928 and subsequently removed.

Donal Fallon quotes from the brief commentary on the statue that comes from a book, ‘Ireland In Pictures’, dating from 1898: "This equestrian statue of William II stands in College Green, and has stood there, more or less, since A.D 1701. We say “more or less” because no statue in the world, perhaps, has been subject to so many vicissitudes. It has been insulted, mutilated and blown up so many times, that the original figure, never particularly graceful, is now a battered wreck, pieced and patched together, like an old, worn out garment."

As historian Fin Dwyer writes: "If there was one statue that was not going to survive Irish independence this was it. William of Orange defeated James II at the battle of the Boyne in 1690 and ever since William and his victory has been twisted to suit political circumstances of the day. His victory had been celebrated by Unionists in the provactive 12th of July Parades in Ireland through the 19th century and he became a despised figure for Irish catholics and nationalists who saw William as a symbol of repression and discrimination. In 1929, the inevitable happened and the statue was blown up. Needless to say it wasn’t rebuilt."

FitzGibbon Memorial (1930)

According to Professor John A Murphy, UCC: "In August 1849, Queen Victoria witnessed her statue being hoisted on the highest gable of the new Queen’s College, now University College Cork. There it remained until 1934 when it was taken down and replaced by Finbarr, Cork’s patron saint. The Victoria statue was put in storage for some years and then bizarrely buried in what was admittedly UCC’s classiest location, the President’s Garden."

King George II (1937)

This equestrian monument of King George II in St Stephen's Green (1758–1937) was blown up on 13 May 1937, the day after the coronation of George VI.

It was unveiled in 1758 and depicted George II in Roman attire. It was placed on a tall pedestal but still 'the victim of many attacks'.

The statue of Queen

Victoria at Leinster House, Kildare Street (1904–1948) was removed in

1948 as part of moves by the Irish State towards declaring a Republic,

and eventually shipped to Sydney, Australia in 1987 where it is now on display on the corner of Druitt and George Street in front of the Queen Victoria Building.

The statue in its original location

According to Wikipedia: "The statue sat atop a portland stone column, also designed by Hughes, with three sculptural groups to be placed below – "Fame", "Hibernia at Peace" and "Hibernia at War". This last group was also known as "Erin and the Dying Soldier" and referred to the loyalty demonstrated by Irish soldiers in the Boer War." Also, that "the associated sculptures from the base of the statue are currently in the collection of Dublin Castle."

One of the sculptural groups from the base in the Leinster House grounds.

(Photo by Mick Kenny)

The

statue in its present location

The anger towards British colonialism in Ireland could be seen in newspaper reports of the time, for example:

"In 1895, The Nation

newspaper noted that Irish migrants in New York had celebrated

Victoria’s Jubilee with “the most appropriate celebration”, staging

demonstrations and distributing political literature to highlight their

view that: "some of the benefits conferred upon Ireland during

Victoria’s murderous reign: Died of famine 1,500,000; evicted 3,668,000;

expatriated 4,200,000; emigrants who died of ship fever, 57,000;

imprisoned under the Coercion Acts, over 3,000; butchered in suppressed

public meetings, 300; Coercion Acts, 53; executed for resisting tyranny,

95; died in English dungeons, 270; newspapers suppressed, 12."

George Howard (1956)

The statue of George Howard (Earl of Carlisle) in the Phoenix Park (1870–1956) was blown off its plinth in an explosion in 1956 and moved to Castle Howard in Yorkshire. The pedestal remains in place as a memorial. George Howard (1802–1864), the 7th Earl of Carlisle, served under Lord Melbourne as Chief Secretary for Ireland between 1835 and 1841.

British War Memorial (1957)

The Gough Monument in the Phoenix Park (1880–1957) was blown up in 1957, it was later restored and re-erected in the grounds of Chillingham Castle, England, in 1990. Field Marshal Hugh Gough, 1st Viscount Gough (1779–1869) was a British Army officer born at Woodstown, Annacotty, Ireland. Gough's colonial credentials are impeccable, serving British forces in China, India and South Africa where he "commanded the 2nd Battalion of the 87th (Royal Irish Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot during the Peninsular War. After serving as commander-in-chief of the British forces in China during the First Opium War, he became Commander-in-Chief, India and led the British forces in action against the Marathas defeating them decisively at the conclusion of the Gwalior Campaign and then commanded the troops that defeated the Sikhs during both the First Anglo-Sikh War and the Second Anglo-Sikh War."

The attack on the Gough Monument demonstrated that being Irish-born was no guarantee of immunity from denunciation and execration. Indeed, the assaults on colonial monuments also became a subject for Irish writers over subsequent decades too. The well-known Irish writer, Myles na gCopaleen, commented on a previous attack on the Gough monument when it was beheaded on Christmas Eve 1944. Writing in his column, Cruiskeen Lawn in The Irish Times in January 1945, he commented:

"Few people will sympathise with this activity; some think it is simply wrong, others do not understand how anybody could think of getting up in the middle of a frosty night in order to saw the head of a metal statue. [...] The Gough statue in question was a monstrosity, famous only for the disproportion of the horse’s legs, its present headlessness gives it a grim humour and even if the head is recovered, I urge strongly that no attempt should be made to solder it on."

The head was eventually found in the River Liffey, the main river running through the centre of Dublin. The fate of the Gough statue is also known because of a poem believed to have been written by another Irish writer, Brendan Behan (though some attribute it to poet Vincent Caprani):

"Neath the horse’s prick, a dynamite stick

Some Gallant hero did place

For the cause of our land, with a light in his hand

Bravely the foe he did face.

Then without showing fear, he kept himself clear

Excepting to blow up the pair

But he nearly went crackers, all he got was the knackers

And made the poor stallion a mare."

Nelson's Pillar (1966)

Nelson's Pillar O'Connell Street (1809–1966) was blown up in 1966 on the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Rising. The head of Nelson's statue was rescued, and is currently on display in the Dublin City Library and Archive on Pearse Street.

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson (1758–1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His naval victories around Europe, Egypt and the Canaries brought him much fame in Britain and an early death at the age of 47. The remaining stump was blown up by the Irish army to the delight of gathered Dubliners who according to the press "raised a resounding cheer".

Nelson in song

The destruction of the pillar soon became the subject of three songs by The

Dubliners, The Go Lucky Four, and The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem,

respectively.

"Oh the Russians and the Yanks, with lunar probes they play

Toora, loora, loora, loora, loo

And I hear the French are trying hard to make up lost headway

Toora, loora, loora, loora, loo

But now the Irish join the race, we have an astronaut in space

Ireland, boys, is now a world power too"

The Go Lucky Four - Up Went Nelson

Another song was called "Up Went Nelson" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=__3v0eKHB_s), "set to the tune of "John Brown's Body" and performed by a group of Belfast schoolteachers known as The Go Lucky Four, which remained at the top of the Irish charts for eight weeks":"One early mornin' in the year of '66

A band of Irish laddies were knockin' up some tricks

They though Horatio Nelson had overstayed a mite

So they helped him on his way with some sticks of gelignite"

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem

– Lord Nelson

In 1967 The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem released an album titled Freedom's

Sons with the song Lord Nelson (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAkjuiVZttk&t=4s)

“Lord Nelson stood in pompous

state upon his pillar high

And down along O'Connell Street,

he cast a wicked eye

He thought how this barbaric race

had fought the British crown

Yet they were content to let him

stay right here in Dublin town

Chorus:

So remember brave Lord Nelson

boys, he had never known defeat

And for his reward, they stuck him

up in the middle of O'Connell Street

Well for many years, Lord Nelson

stood and no one seemed to care

He'd squint at Dan O'Connell, who

was standing right down there

He thought "The Irish like

me or they wouldn't let me stay

That is except those blighters

that they call the I.R.A."

Chorus

And then in 1966, on March the

seventh day

A bloody great explosion made

Lord Nelson rock and sway

He crashed and Dan O'Connell

cried in woeful misery

"There are twice as many

pigeons now will come and s(h)it on me"

So remember brave lord Nelson

boys, he had never known defeat

And for his reward, they blew him

up in the middle of O'Connell Street”

(https://www.allthelyrics.com/lyrics/tommy_makem/lord_nelson-lyrics-1130982.html)

Taoiseach and President of Ireland, Eamon DeValera apparently found the explosion amusing:

"Senator David Norris, who thought the bombing ignorant and unnecessary, told RTE: ‘It provoked the only recorded instance of humor in that lugubrious figure, the late President of Ireland Eamon De Valera, who is said to have phoned the Irish Press to suggest a headline ‘British Admiral Leaves Dublin By Air.’"

And Nelson’s head? According to irishcentral.com:

“What happened to Nelson’s head after the explosion merits a mention. Seven hearty students from the National College of Art and Design reportedly stole it on St. Patrick's Day from a storage shed in Clanbrassil Street. Later they leased the head for over $300 dollars a month to an antique dealer in London for his shop window. Then it reappeared sometime later on the stage of the Olympia Theatre for a concert performance with The Dubliners. After further comical wanderings (which included an unlikely appearance in a ladies' stockings commercial) the high-spirited students finally handed it over to Lady Nelson. It was later stored in the Civic Museum in Dublin and now resides in the Gilbert Library, on Pearse Street where it’s now rarely seen.”

Despite the regularly re-engineered cityscape of Dublin, the way was not cleared for a spate of representations of Irish national heroes. What was erected tended to be mythologisations of Irish history (the Children of Lir in the Garden of Remembrance, Cú Chulainn in the GPO: see my 1916 article) as if Irish elites feared the posthumous visages of its bravest and the effect their presence might have on the Dublin populace. What revolutionary figures that do exist in statue form (Tone, Emmett, Connolly etc) tend to be tucked away in parks or on side streets while the main bourgeois nationalist heroes stand on large plinths on Dublin's main streets (O'Connell, Parnell etc).

The lack of a major monument on a major street in Dublin commemorating, for example, the Great Hunger or the Seven Signatories of the 1916 Proclamation shows that, despite the decades of resistance to an imposed history, we are still not allowed to commemorate our own.

web.jpg)