Bonfire Night, St. John's Eve by Jack Butler Yeats (Ireland)

Traditional summer festivals have always revolved around the solstice and

bonfires on the feast of St. John (24 June) in many countries. Maypole dancing

was also an important aspect of some rural and agricultural summer events, and

other summer festivals like Ferragosto (15 August), involved celebrating the

early fruits of the harvest and resting after months of hard work. The summer

solstice was seen as the height of the powers of the sun which has been

observed since the Neolithic era as many ancient monuments throughout Eurasia

and the Americas aligned with sunrise or sunset at this time. In the ancient

Roman world, the traditional date of the summer solstice was 24 June, and "Marcus Terentius

Varro wrote in the 1st century BCE that Romans saw this as the middle of

summer."

Saint John's Fire with festivities in front of a Christian calvary shrine in Brittany, 1893

Ferragosto (Feriae Augusti ('Festivals [Holidays] of the Emperor Augustus')

were celebrated in Roman times on August 1st "with horse racing, parties and

lavish floral decorations. Inspired by the pagan festival for Conso [Consus],

the Roman god of land and fertility." The pagan Italian deity,

Consus, who was a partner of the goddess of abundance, Ops is believed to have come from condere (“to store

away”), and so was probably the god of grain storage. The holiday of the Emperor

Augustus was celebrated during the month of August with events based around the

harvest and the end of agricultural work, and involved the rural community who

were able to take a break from the back-breaking work of the previous weeks. In

the 7th century, the Catholic Church in Italy adopted the holiday but changed

the date of celebration from August 1st

to August 15, to coincide with the celebration of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary so as "to

impose a Christian ideology onto the pre-existing celebration".

Therefore, historically the midsummer festivities ranged from mid June to mid

August as the strength of the sun went into decline and the fruits of the

harvest were beginning to come in.

However, compared to the other seasonal festivals, such as Christmas, Easter,

and Hallowen, which have a very strong presence in the media and in the shops,

but not the summer festivals. Why is this? Except for commercial music and arts

festivals, there are no major commercialised products associated with the

historical summer agricultural and fertility rites. For example, Christmas's

rebirth is associated with Santa Claus, Christmas trees, and the giving of

presents. Easter's new life festival is celebrated with dyed eggs, chocolate

eggs and chocolate bunnies. Halloween's reminders of death and the departed are

celebrated with 'trick or treating', pumpkins, and bonfires.

In all these cases the combination of commercialisation and tradition has seen

reciprocal relationships as one feeds off the other. The globalised media and

cinema indulge in the myths of each season creating updated versions of their

traditions that result in new economic and cultural products, for example, the

growing of pumpkins in Ireland to replace the original turnip lanterns that the

Irish brought to the USA, or new movies based on new twists on the myths of

Christmas. These aspects keep nature-based pagan festivals alive in the mind of

the public throughout most of the year.

Not so with summer. In general there seems to be no particular object or

tradition to exploit or commercialise, or at least not yet. There are various

possible reasons.

The Feast of Saint John by Jules Breton (1875).

In the last 100 years or so we have seen a societal change from the community

to the nuclear family. The general increase in wealth since the 1960s has

resulted in mass international travel for summer holidays and tourism. The

overall result of these changes in family, lifestyle, and the growth of

non-agricultural occupations has seen people becoming more and more

disconnected from the land and the agricultural traditions associated with farming

and harvests. This was combined with the monopolisation and globalisation of

agricultural production, and the international trade of agricultural goods.

Despite all of this, there are midsummer traditions that are persisting,

although with a much lower profile than the other seasonal festivities.

What were the summer pagan traditions? Probably the strongest of the summer

traditions is the bonfires of the feast of St. John. In the 13th century CE, a

Christian monk of Lilleshall Abbey in England, wrote:

"In the worship of St John, men waken at even, and maken three manner of

fires: one is clean bones and no wood, and is called a bonfire; another is of

clean wood and no bones, and is called a wakefire, for men sitteth and wake by

it; the third is made of bones and wood, and is called St John's Fire."

In Ireland, St John's Eve bonfires are still lit on hilltops in various parts

of the country. According to

Marion McGarry:

"Since the distant past, bonfires lit by humans at midsummer greeted the

sun at the height of its powers in the sky. The accompanying ritual

celebrations were primal, restorative, linked with fertility and growth.

Midsummer and the time around St John's Day have been traditionally celebrated

throughout Europe."

Midsummer festival bonfire (Mäntsälä, Finland)

The bonfires were associated with purification and luck. Every aspect of the

fire was important and taken into account: the flames, the smoke, the hot

embers, and even the ash:

"Jumping through the bonfire was a common custom. A farmer might do this

to ensure a bigger yield for his crops or livestock, while engaged couples

would jump together as a sort of pre-wedding purification ritual. Single people

jumped through in the hope it would bring them a future spouse. Finally, the

fire was raked over and any cattle not yet at the summer pasture were driven

through the smouldering smoke and ashes to ensure good luck. The remaining ash

was scattered over crops or could be mixed into building materials to encourage

good luck in a building. The ash was considered curative too, and some mixed it

with water and drank as medicine. Embers were brought into the house as

protective talismans."

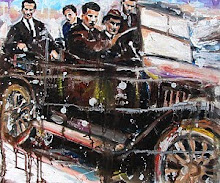

It was reported that John Millington Synge (playwright) and his friend, Jack B. Yeats (artist and illustrator) attended a St. John's Eve celebration on a visit to County Mayo, Ireland, in 1905. At first, "they had been saddened by the depressed state of the area, but then Synge is quoted as saying: "...the impression one gets of the whole life is not a gloomy one. Last night was St. John's Eve, and bonfires - a relic of Druidical rites - were lighted all over the country, the largest of all being in the town square of Belmullet, where a crowd of small boys shrieked and cheered and threw up firebrands for hours together." Yeats remembered a little girl in the crowd, in an ecstasy of pleasure and dread, clutching Synge by the hand and standing close in his shadow until the fiery games were over."

Bonfires were lit to honor the sun and to protect against evil spirits which

were believed to roam freely when the sun was turning southward again. They were

"both a celebration of and devotion to the natural world."

Maypoles were erected either in May or at midsummer as part of European

festivals and usually involved dancing around the maypole by members of the

community. It is not known exactly what the symbolism of dancing around the

maypole is but most theories revolve around pagan ideas, e.g., Germanic

reverence for sacred trees or as an ornament to bring good luck to the

community. In England:

"the dance is performed by pairs of boys and girls (or men and women) who

stand alternately around the base of the pole, each holding the end of a

ribbon. They weave in and around each other, boys going one way and girls going

the other and the ribbons are woven together around the pole until they meet at

the base."

Dance around the Maypole by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, 16th century

When the

church authorities could not co-opt pagan festivals like Ferragosto they banned

them. For example, Kupala Night is one of the major folk holidays of the

Eastern Slavs that coincides with the Christian feast of the Nativity of St.

John the Baptist and involved activities

"such as gathering herbs and flowers and decorating people, animals, and

houses with them; entering water, bathing, or dousing with water and sending

garlands on water; lighting fires, dancing, singing, and jumping over fire; and

hunting witches and scaring them away".

In medieval Russia, these rituals and games were considered demonic and the

hegumen [head] Pamphil of the Yelizarov Convent (1505) wrote to the Pskov

governor and authorities describing them thus in the

Epistle of Pamphilus of Yelizarov Monastery:

"For when the feast day of the Nativity of Forerunner itself arrives, then on this holy night nearly the entire city runs riot and in the villages they are possessed by drums and flutes and by the strings of the guitars and by every type of unsuitable satanic music, with the clapping of hands and dances, and with the women and the maidens and with the movements of the heads and with the terrible cry from their mouths: all of those songs are devilish and obscene, and curving their backs and leaping and jumping up and down with their legs; and right there do men and youths suffer great temptation, right there do they leer lasciviously in the face of the insolence of the women and the maidens, and there even occurs depravation for married women and perversion for the maidens."

Couple jumping over a bonfire in Pyrohiv, Ukraine on Kupala Night.

In another commentary from Stoglav (chapter 92, a collection of decisions of the Stoglav Synod of 1551) it was written:

"And furthermore many of the children of Orthodox Christians, out of simple ignorance, engage in Hellenic devilish practices, a variety of games and clapping of hands in the cities and in the villages against the festivities of the Nativity of the Great John Prodome; and on the night of that same feast day and for the whole day until night-time, men and women and children in the houses and spread throughout the streets make a ruckus in the water with all types of games and much revelry and with satanic singing and dancing and gusli [ancient Russian instrument plucked in the style of a zither] and in many other unseemly manners and ways, and even in a state of drunkenness."

However,

the importance of festive holidays lies in their value for reconnecting with

family, friends and community. Michele L. Brennan examines the psychological

aspects of traditional celebrations:

"Holiday traditions are essentially ritualistic behaviors that nurture us

and our relationships. They are primal parts of us, which have survived since

the dawn of man. Traditional celebrations of holidays has been around as long

as recorded history. Holiday traditions are an important part to building a

strong bond between family, and our community. They give us a sense of

belonging and a way to express what is important to us. They connect us to our

history and help us celebrate generations of family. Children crave the comfort

and security that comes with traditions and predictability. This takes away the

anxiety of the unknown and unpredictable."

Maypole dance during Victoria Day in Quebec, Canada, 24 May 1934

The seasonal festivals were based on the very real fear and anxiety of human

survival, focussing on the means of sustenance: agricultural production. The

vagaries of weather patterns meant that there was never any guarantee that

fruits and crops would survive until successful harvesting.

While much of this anxiety was quelled by changes in the agricultural

production methods of the twentieth century. However, now, in the twenty-first

century, there is an ever growing recognition that modern agricultural systems

are untenable, and that a new emphasis on alternative and sustainable food

growing practices is essential:

"Increasingly, food growers around the world are recognizing that modern

agricultural systems are unsustainable. Practices such as monocultures and

excessive tilling degrade the soil and encourage pests and diseases. The

artificial fertilizers and pesticides that farmers use to address these

problems pollute the soil and water and harm the many organisms upon which

successful agriculture depends, from pollinating bees and butterflies to the

farm workers who plant, tend and harvest our crops. As the soil deteriorates,

it is able to hold less water, causing farmers to strain already depleted water

reservoirs."

However, this in contrast with technocratic elites who have a very different

perspective on the future of food, as Colin Todhunter writes:

"It involves a shift towards a ‘one world agriculture’ under the control

of agritech and the data giants, which is to be based on genetically engineered

seeds, laboratory created products that resemble food, ‘precision’ and

‘data-driven’ agriculture and farming without farmers, with the entire agrifood

chain, from field (or lab) to retail, being governed by monopolistic e-commerce

platforms determined by artificial intelligence systems and algorithms."

While science and education has contributed to the changes in beliefs

associated with ancient traditions revolving around purification and fertility,

the psychological aspects of traditional holidays remain important.

Furthermore, the growing awareness of the importance of good organic food is

gradually competing with the monopolistic trends of globalist agritech.

The observance of traditional festivals, with their emphasis on nature and the

annual cycle of seasonal changes focus attention on the here-and-now, on living

according to our means and resources, and is a far cry from the teleological

ideologies of patriarchal religion. The Christian church diverted people's

attention away from a practical, scientific cosmology towards their own heroes

and saints who provided individualistic examples of concern for one's own

destiny after death and 'judgement' in the far future, as being more important

than our present relationship with nature.

Over the centuries this process formed a gradual alienation of people away from

nature itself, helped along now by the constant monopolisation of land, and the

growth of agritech giants.

Dancing around the midsummer pole, Årsnäs in Sweden, 1969.

Instead of

respecting the land, farmers use intensive farming to maximize yields, using

more and more fertilizer and pesticides, depleting the nutrients of the soil

and causing desertification to spread. When I was growing up, local annual

horticultural festivals and competitions emphasised diversity, production over

consumption, and quality food produced locally. Traditional festivals, with

their focus on sun cycles and the seasons, complemented and structured our

relationship with nature, as well as work and rest, life and death.

It is necessary to re-focus our attention back on this life, on how we plan to

organise our basic sustenance into the future, and in a sustainable way, before

others turn nature into a desert, a dust bowl of gigantic proportions, in their

constant, remorseless drive to convert the earth into profit.

.jpg)

.JPG)