70th anniversary of NATO

This

year marks the 70th anniversary of the founding of NATO with the

signing of the North Atlantic Treaty on 4 April 1949. Established as a

peacetime alliance between the United States and Europe to prevent

expansion of the Soviet Union, NATO has grown in size and changed

from a defensive force to an aggressive force implementing Western

policies of expansion and control.

NATO now has 29 members

ranging geographically east to west from the United Kingdom to countries

of the former Soviet Union and north to south from Norway to Greece.

NATO's intervention in the Bosnian war in 1994 signaled the beginning of

a new role for a force effectively made redundant by the collapse of

the Soviet Union in 1991. Since then NATO has escalated its presence on

the international scene taking on various roles in Afghanistan in 2003,

Iraq in 2004, the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean in 2009 and

culminated in the bombing of

Libya in 2011 with '9,500 strike sorties against pro-Gaddafi targets.'

The

main argument for the existence of NATO was for it to be a system of

collective defence in response to external attack from the Soviet Union.

Although during the Cold War NATO did not carry out military operations

as a defence force, its changing role has now implicated its members in

a culture of aggressive war which they had not originally signed up

for.

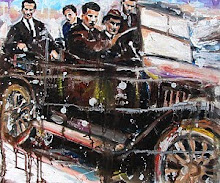

For former colonial powers the NATO culture of war on a

global scale is nothing new. The geopolitical agendas of expansionism

for Western elites that NATO serves is the modern form of the colonial

adventures of the past which have long passed their sell-by date. The

culture of war which passes for 'the white man's burden', 'bringing

freedom to other countries' or 'saving them from communism' legitimizes

aggressive action abroad while giving a sense of pride at home of a

worthwhile military doing a great job.

War as a means to an end and war as culture

The

culture of war then is different from culture wars (e.g. competing

forms of culture like religion). Since the Enlightenment, war has been

described as a means to an end, serving essentially rational interests.

The benefits of war at home like ending the feudal system, repelling

invaders, etc. were seen to apply abroad too by helping others through

systems of alliances, for example the Second World War alliance to end

Hitlerite fascism.

However, there are those who see war as an end in itself, as part of the human condition. Writers like Martin Van

Creveld have argues that:

"war

exercises a powerful fascination in its own right — one that has its

greatest impact on participants but is by no means limited to them.

Fighting itself can be a source of joy, perhaps even the greatest joy of

all. Out of this fascination grew an entire culture that surrounds it

and in which, in fact, it is immersed."

However, not all cultures

of war are the same. Van Creveld conflates the culture of war of

imperial nations with the culture of war of resistance to colonialism

and imperialism. Britain's wars were fought for the benefit of British

elites. But Ireland, for example, has a long history of opposition to

British colonialism and Ireland's culture of war has similar symbols and

traditions to Britain yet very different content. Over the centuries

generation after generation of Irish men and women have taken part in

wars of resistance to colonial domination. While the British culture of

war may have been a proud culture of successful militarism, in Ireland

it was a desperate fight for independence from an all-powerful enemy

always willing to throw its vast armory into the fight against

'treachery to the King'.

In other words, the culture of war was

imposed on a people as a way to survive military, economic and political

domination. Which brings up the question of whether war really is a

part of the human condition.

War and 'primitive tribes'

It

has been a Romantic trope to look back to the 'primitive tribes' as a

way of understanding our own society and how they may have looked before

feudalism and the burgeoning capitalism's 'satanic mills' were set in

motion. Yet, it is interesting to see the descriptions of 'primitive

people' from our history books, as

Zinn writes:

"When

Columbus and his sailors came ashore, carrying swords, speaking oddly,

the Arawaks ran to greet them, brought them food, water, gifts. [...]

These Arawaks of the Bahama Islands were much like Indians on the

mainland, who were remarkable (European observers were to say again and

again) for their hospitality, their belief in sharing."

Bartolome de las Casas, who, as a young priest, participated in the conquest of Cuba, wrote:.

"They

are not completely peaceful, because they do battle from time to time

with other tribes, but their casualties seem small, and they fight when

they are individually moved to do so because of some grievance, not on

the orders of captains or kings."

Their resorting to violence and killing was a form of defence which ultimately failed:

"On

Haiti, they found that the sailors left behind at Fort Navidad had been

killed in a battle with the Indians, after they had roamed the island

in gangs looking for gold, taking women and children as slaves for sex

and labor.[...] Total control led to total cruelty. The Spaniards

"thought nothing of knifing Indians by tens and twenties and of cutting

slices off them to test the sharpness of their blades." Las Casas tells

how "two of these so-called Christians met two Indian boys one day, each

carrying a parrot; they took the parrots and for fun beheaded the

boys." The Indians' attempts to defend themselves failed. And when they

ran off into the hills they were found and killed."

Thus, we can

see that while there was occasional violence against other tribes these

tribes lived in peace until faced with the extreme violence of their

invaders.

Development of warrior societies

Recent

research in archeology seems to suggest now that we don't need to look

to 'primitive tribes' abroad anymore but can see similar experiences in

research on our own ancestors here in Europe and nearby regions.

In an article by John Horgan,

Survey

of Earliest Human Settlements Undermines Claim that War Has Deep

Evolutionary Roots, he looks at the recent work of anthropologist Brian

Ferguson, an authority on the origins of warfare:

"Ferguson

closely examines excavations of early human settlements in Europe and

the Near East in the Neolithic era, when our ancestors started

abandoning their nomadic ways and domesticating plants and animals.

Ferguson shows that evidence of war in this era is quite variable. In

many regions of Europe, Neolithic settlements existed for 500-1,000

years without leaving signs of warfare. "As time goes on, more war signs

are fixed in all potential lines of evidence—skeletons, settlements,

weapons and sometimes art," Ferguson writes. "But there is no simple

line of increase." By the time Europeans started supplementing stone

tools with metal ones roughly 5,500 years ago, "a culture of war was in

place across all of Europe," Ferguson writes. "After that," Ferguson

told me by email, "you see the growth of cultural militarism,

culminating in the warrior societies of the Bronze Age.""

It

seems then that the history of the development of warrior societies and

their enslavement of peaceful peoples is the basis for our cultures of

war: the wars of those imposing slavery on people and the wars of those

resisting.

The idea of an inherent human condition of war

promoted by Van Creveld may be covering up for the felt need or desire

for a culture of war to dissuade those who may be thinking of imposing

slavery or dominance on a people, as a form of defence in an aggressive,

militarized world, for example, the Jews in Nazi Germany .

The

Irish people have a long history of resistance to British forces and

Ireland's long experience of foreign aggression has led it to be wary of

foreign military associations. Thus, today Ireland is still not a fully

paid up member of NATO. In the nineteenth century the British used

every form of simianism and Frankensteinism to depict the Irish people

who had the gall to combine against them.

Ridiculing resistance: "The Irish Frankenstein" (

1882) and "Mr. G O'Rilla, the Young Ireland Party" (

1861)

This

all changed during the First World War when Britain desperately needed

new recruits and issued posters now depicting a proud Irishman as a

country squire. Guilt was the weapon of choice in these posters as

Britain declared to be fighting for the rights of small nations like

Ireland, who was not participating.

WWI British Army Recruitment Posters: "Ireland "I'll go too - the

Real Irish Spirit"" and "Ireland "For the

Glory of Ireland""

Of

course, after the war was over and the main nationalist party, Sinn

Fein, won 80% of the national vote, the British government's reaction

was to send in soldiers and criminals to put down the rebellion instead.

This strategy failed, leading to negotiation and the signing of a

treaty which led to the creation of Northern Ireland.

Ireland's culture of resistance: the Wexford

Pikeman by Oliver Sheppard and IRA

Memorial, Athlone

Ireland and NATO

In

1949 Ireland had been willing to negotiate a bilateral defence pact

with the United States, but opposed joining NATO until the question of

Northern Ireland was resolved with the United Kingdom. However,

Ireland became a signatory to NATO's Partnership for Peace programme and the alliance's Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council in 1999.

In December 1996, the Peace & Neutrality Alliance (PANA) was established in Dublin. According to their

website,

'PANA seeks to advocate an Independent Irish Foreign Policy, defend

Irish Neutrality and to promote a reformed United Nations as the

Institution through which Ireland should pursue its security concerns.'A

wide range of groups and a growing number of individual are affiliated

to PANA. This wide anti-NATO sentiment was reflected in the attack on US

military planes in 2003. In February 2003 the Irish Times

reported:

“The

Army has been called in to provide security around Shannon Airport

after five peace activists broke into a hangar and damaged a US military

aircraft early this morning. It is the third embarrassing security

breach at the airport where US military planes are refuelling en route

to the looming war with Iraq.”

One anti-war activist Mary Kelly

was convicted of causing $1.5m in damage to a United States navy plane

at Shannon airport. She attacked the plane with a hatchet causing damage

to the nose wheel and electric systems at the front of the

plane.

In 2018 the First International Conference Against NATO was held in Dublin. The conference was

organised by the Global Campaign Against US/NATO Military Bases which itself is a coalition of peace organisations from around the world.

However,

there are still forces in Ireland pushing for full membership of NATO. A

recent article in an Irish national newspaper stated that 'Ireland has

been free-riding on transatlantic security structures paid for by

American and European taxpayers since 1949' and that 'very few

politicians think much about Ireland's security in any depth and even

fewer believe we should join NATO. None is likely to provide grown-up

leadership on national security.' A combination of realism and guilt

that has been tried on the Irish people many times before and rejected.

The writer

recognises that 'few people advocate such a course and most are quite attached to the State's long-held position of military neutrality.'

Conference on the 70th Anniversary of NATO

Getting

other nations to develop a similar attitude and leave NATO was the

objective of the recent International Conference on the 70th Anniversary

of NATO held in Florence, Italy, on 7 April 2019. During the conference

Prof. Michel Chossudovsky (Director of the Centre for Research on

Globalization) presented the The Florence Declaration which was adopted

by more than 600 participants. The Florence Declaration was drafted by

Italy’s Comitato and the CRG and

calls

for members "To exit the war system which is causing more and more

damage and exposing us to increasing dangers, we must leave NATO,

affirming our rights as sovereign and neutral States.

In this

way, it becomes possible to contribute to the dismantling of NATO and

all other military alliances, to the reconfiguration of the structures

of the whole European region, to the formation of a multipolar world

where the aspirations of the People for liberty and social justice may

be realised."

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork

consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well

as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing

based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of

Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed

country by country here. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization.