The drum is always there. In life and death. In between is dance. Always the drum is everywhere.

Peniel Guerrier

I don't think this world was made for a small minority to dance on the faces of everyone else.

H.G. Wells (In the Days of the Comet)

Nothing happens until something moves.

Albert Einstein

Introduction

The

dance group Diversity's 'I Can't Breathe' routine evoked around 24,500

complaints from members of the public when it aired on ITV on 5

September, 2020. The performance was inspired by the killing of George

Floyd in the USA. Its choreography references progress from stock market

bubbles, the growth of digital shopping, the effect of mobile phones on

family life, the coronavirus pandemic and subsequent lockdowns, to the

killing of George Floyd, and then ending with street protests and the

riot police. The show was a spectacular mix of spoken word, song, visual

and stage effects, as well as Diversity's trademark blend of complex

routines, breakdancing, backflips and theatricality.

Diversity's 'I Can't Breathe' routine - https://www.youtube.com/watch?

While

the troup garnered much international praise for the 4 1/2 minute

anti-racist performance, the many complaints focused on its political

content. According to Ashley Banjo, troupe member and choreographer, "We

got bombarded with messages and articles … horrible stuff about all of

us, our families … it’s sad."

This level of negative public reaction to a dance routine on TV in the UK was unprecedented.

Dance

has been an important part of of TV entertainment, especially in the UK

and the USA, since the 1960s with shows such as American Bandstand and

Soul Train, dance groups on Top of the Pops and in more recent decades,

shows such as Dancing on Ice, Dancing with the Stars, So You Think You

Can Dance and Strictly Come Dancing.

However, maybe the

innocuousness of such TV history has lulled people into seeing dance as

pure entertainment, safe from the radical social commentary that other

artforms put on display now and then in theatres, galleries and cinemas.

The

history of dance shows that it has always been with us, and, like with

other art forms, dance has a mixed history of social and radical roles.

It has also, like other art forms, been highly influenced by

Enlightenment and Romanticist ideas in more recent centuries, changing

how we see and understand the role of dance in society today.

In

this article I will examine how dance has changed since the

Enlightenment and why it has had an increasing popularity in the last

century. I will also look at the potential for a radical dance culture

to become a vehicle for increasing social and political awareness on a

global scale.

Early and medieval dance history

Dance

has been a part of human culture from prehistoric times to Egyptian tomb

paintings depicting dancing figures from c. 3300 BC. Folk dance, in

particular, has been an important part of festivals, seasonal

celebrations and community celebrations such as weddings and births.

In

Europe during the Middle Ages there are references to circular dances

called 'carole' from the 12th and 13th centuries. People also danced

around trees holding hands in a leader and refrain style. These dances

and songs became the carols we know today.

However, the literary history of dance in terms of detailed descriptions goes back to Italy in the middle of the fifteenth century after the start of the Renaissance. During this time there also developed a divergence between court dances and country dances, between performance and participation. Court dancers trained for dances for entertainment, while anyone could learn country dances. At court formal display dancing would be followed by informal country dances for all to participate in.

Ballet also began at this time developing out of court pageantry in Italy at aristocratic weddings. Its choreography was based on court dance steps and performers dressed in the formal gowns of the time rather than the later tutus and ballet slippers.

It was then brought to France by Catherine de' Medici in the 16th century where it developed into a performance-focused art form during the reign of Louis XIV where: "His interest in ballet dancing was political motivated. He established strict social etiquettes through dancing and turned it into one of the most crucial elements in court social life, effectively holding authority over the nobles and reigning over the state."

By the 17th century ballet became professionalised and its challenging acrobatic movements could "only be performed by highly skilled street entertainers."

The Enlightenment and ballet in the 18th century

It

was ballet that also became a focal point for criticism by the

Enlightenment philosophes during the 18th century. Philosophes (French

for 'philosophers') "were public intellectuals who applied reason to the

study of many areas of learning, including philosophy, history,

science, politics, economics, and social issues."

The philosophes

"argued that ancient superstitions and outmoded customs should be

eliminated, and that reason should play a major role in reforming

society." They desired to see "the development of art forms that gave

meaningful expression to human thoughts, ideas, and feelings, and they

disregarded merely decorative or ornamental forms of art."

Denis Diderot, for example, (one of the editors of the quintessential enlightenment project: the Encylopédie) wrote in his essay 'Entretiens sur 'Le Fils Naturel'':

"I would like someone to tell me what all these dances performed today represent — the minuet, the passe-pied, the rigaudon, the allemande, the sarabande — where one follows a traced path. This dancer performs with an infinite grace; I see in each movement his facility, his grace, and his nobility, but what does he imitate? This is not the art of song, but the art of jumping. A dance is a poem. This poem must have its own way of representing itself. It is an imitation presented in movements, that depends upon the cooperation of the poet, the painter, the composer, and the art of pantomime. The dance has its own subject which can be divided into acts and scenes. Each scene has a recitative [type of singing that is closer to speech than song] improvised or obligatory, and its ariette [a short aria]."

To achieve this the philosophes argued for more naturalism in style and less of the "contrived sophistication and majesty" of earlier Baroque aesthetics. This criticism eventually led to new forms of ballet "that attempted to convey meaning, drama, and the human emotions" in particular the ballet d'action: "a dance containing an entire integrated story line".

Ballet in the 19th century: Romanticism

Enlightenment

ideas which led to the 'Age of Reason' and classical ideas of order,

harmony and balance gave way to Romanticist emphasis on emotion,

individualism and anti-rationalist medievalism. The "vogue for exotic,

escapist fantasy which dominated Romanticism in all the other arts" soon

affected ballet in two major aspects: a new preoccupation with the

supernatural, and the exotic. The plots in Romantic ballet:

"were

dominated by spirit women—sylphs [imaginary spirits of the air], wilis

[a type of supernatural being in Slavic folklore], and ghosts—who

enslaved the hearts and senses of mortal men and made it impossible for

them to live happily in the real world. Women dancers were dressed in

diaphanous white frocks with little wings at their waist, and were

bathed in the mysterious poetic light created by newly developed gas

lighting in theatres. They danced in a style more fluid and ethereal

than 18th-century dancers and were especially prized for their ballon

[the ability to appear effortlessly suspended while performing movements

during a jump] as they tried to create the illusion of flight."

The second important Romantic influence in ballet was:

"a

fascination with the exotic, which was figured through gypsy or

oriental heroines and the use of folk or national dances from ‘foreign’

cultures (such as Spain, the Middle East, and Scotland). Such dances

were considered highly expressive both of character and of exotic local

colour, though in some countries, such as Italy, indigenous dances were

featured in ballets whose plots reflected that region's surge of

nationalist feeling."

An early example of the Romantic ballet is

La Sylphide which was first performed at the Paris Opera in 1823

starring Marie Taglioni:

"La Sylphide is a story ballet about a

supernatural female creature, half-woman, half-bird, who is doomed to an

eternity of dancing. The Sylphide falls in love with a peasant man,

James, who is soon to be married. However, James falls in love with the

sylphide and leaves his wedding to spend his life with her. The ballet

takes a turn when James consults a witch on how to keep the Sylphide

from flying off. The witch tells him to tie a scarf around the

Sylphide’s waist, and James obeys. The scarf ends up killing the

Sylphide, and James is ultimately killed by the witch in an attempt to

avenge her death. The Sylphide is symbolic of an unattainable dream, and

James is the naive hero who pursues her. This ballet was the first

romantic ballet and typifies the romantic themes of fantasy,

supernaturalism and man vs. nature."

However, it was also the

19th century which saw the creation of what is considered by many to be

the finest achievement of the Classical style, Sleeping Beauty. As

Victoria Rose Niblett writes:

"Sleeping Beauty is opulent,

returning to the intermingling of traditional French court dances in the

choreography and the refinement of the Apollonian [relating to the

rational, ordered, and self-disciplined aspects of human nature as

opposed to Dionysian characteristics of excess, irrationality, lack of

discipline, and unbridled passion] expression. This was a shift away

from the emotional exploration of the Romantic period and back to reason

and rational philosophy. [...] In the Romantic period, dance was

designed by the external power of the music, but in the Classical period

choreographers had a more influential role with the construction of the

symphony. This involvement allowed choreography to follow an academic,

pattern-oriented structure that insured the association between dance

and music. [...] While Romantic ballet focused on fragile and emotional

femininity, Classical ballet focused more on the type of femininity that

could be expressed in the refinement, strength, and charm of the female

character."

While this era saw the rise of ballet as a truly international art form, Romanticism in ballet declined rapidly "as ballets were so weighted towards the feminine and the febrile", while "male dancers were frequently relegated to the role of porteur [supporting the ballerina]".

Folk dance and Herder

The

rise of nationalist feeling in the 19th century was also associated

with the new emphasis on local culture and traditions. Folk dances

attained a new significance as the spread of nationalist and socialist

ideas gave a new emphasis and importance to the culture of the peasants

and the working classes. In Ireland, for example, céilí dances were

popularised by Conradh na Gaeilge (Gaelic League) in its goal to promote

Irish cultural independence and de-anglicisation.

It was the

18th century Enlightenment philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder

(1744–1803) who recognised the importance of traditional culture. Herder

established fundamental ideas concerning the intimate dependence of

thought on language which "appears in its greatest purity and power in

the uncivilized periods of every nation." Hence Herder's interest in

collecting ancient German folk songs. His focus upon language and

cultural traditions as the ties that create a 'nation' "were extended to

include folklore, dance, music and art."

Herder developed his folk theory to the point of believing that "there is only one class in the state, the Volk, (not the rabble), and the king belongs to this class as well as the peasant". His idea that the Volk was not the rabble was a new idea at this time, and thus Herder laid the basis for the idea of "the people" as the basis for later democratic ideologies.

Therefore, as Vicki Spencer writes:

"Herder's intention, then, was not to urge moderm intellectuals and artists to reject the philosophical and intellectual features of their own culture in favor of the simple naivety of earlier folk literature. Instead, he argued that their relationship to their own culture needed to change, in order to capture the complexities and spontaneity in the way of life, language, and character of their own unique culture." [1]

Moreover, Herder believed it was important to look back through history for the nation to 'grow organically' into the future. According to David Denby:

"Herder believes in a human drive towards perfection and self-improvement, but this is a process which operates always in given contexts and within given constraints, which must be understood and respected historically. It is when societies are denied the opportunity to grow organically that they fail to progress. Tradition and progress are not opposites: progress must emerge out of a social and historical tradition if it is to take root, and, conversely, ‘a living tradition was inconceivable without the progressive emergence of new goals’." [2]

Later, Herder's ideas on folk culture became strongly associated with Romanticism and national chauvinism. However, Herder "understood and feared the extremes to which his folk-theory could tend" and he "refused to adhere to a rigid racial theory, writing that 'notwithstanding the varieties of the human form, there is but one and the same species of man throughout the whole earth'."

Thus Herder saw the importance of understanding one's own culture as a foundation stone for future national projects to be built upon, and not about seeing the past as a Golden Age to be nostalgic about as in Romanticist theory.

The twentieth century and Modernism

By the

beginning of the twentieth century folk dance was firmly established and

formed an important part of national culture. Many countries around the

world had state folk dance ensembles by the middle of the century. In

particular this could be seen in the Soviet Union after the Russian

revolution of 1917 where the state supported and promoted folk dance as

part of the culture of the people. The Red Army Choir, an official army

choir of the Russian armed forces, was set up in the 1920s, and by the

1930s was touring with an ensemble of dancers.

(Also known as the Red Army Choir and the Song and Dance Ensemble of the Russian Army)

Ballet continued life after the revolution too but with new revolutionary content. As Georg Predota writes:

"Ballet companies had to cope with a mass exodus of leading figures of the stage, but also defend against grassroots Communist voices that decried ballet as an artificial, frivolous art form, a decadent playground for grand dukes hopelessly out of touch with reality. Yet gradually, government policy opened the former bastions of imperial high culture to the masses, making ballet performances available to a wider audience by distributing free or subsidized tickets."

For example, the Russian ballet, The Red Poppy, with a score written by Reinhold Glière, was created in 1927 and was a huge success. It had a modern revolutionary theme, as Predota notes:

"Set in a port in Kuomintang China in the 1920’s, The Red Poppy eventually became the first truly Soviet ballet. The story tells of the love between a Soviet sailor and a Chinese girl, who is eventually killed by the sailor’s capitalist rival. The tyrannical British imperialist commander of the port sanctions her murder, as Tao-Hoa tries to escape her homeland on board a Soviet ship. As she falls dying, she gives her compatriots a red poppy as an emblem in their fight for freedom."

In Europe the ballet company Ballet Russes, was formed in 1909 and toured Europe as well as North and South America. Although set up by the Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev (and even used Russian dancers), the company never performed in Russia. It became part of the Modernist movement with music commissioned from Rimsky-Korsakov and Stravinsky and the designs of Picasso, Rouault, Matisse, and Derain.

Modernism - an extension of Romanticist thinking - emphasised individualism, art for art’s sake, suspicion of reason, subjectivism and rejected Enlightenment ideas. In the arts, Modernism tended to emphasise constantly changing form over sociopolitical content and this became particularly notable in the twentieth century.

Dance in general also developed in many different directions in the twentieth century but the Modernist movement set the stage for dance trends and styles in the United States and Europe which tended to emphasise individualism and diversion, and then later developed into freestyle. This could be seen in western concert or theatrical dance where modern dance continued as an art form:

"Modern dance is a broad genre of western concert or theatrical dance, primarily arising out of Germany and the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modern dance is often considered to have emerged as a rejection of or rebellion against, classical ballet. Socioeconomic and cultural factors also contributed to its development. In the late 19th century, dance artists such as Isadora Duncan, Maud Allan and Loie Fuller were pioneering new forms and practices in what is now called aesthetic or free dance for performance. These dancers disregarded ballet's strict movement vocabulary, the particular, limited set of movements that were considered proper to ballet and stopped wearing corsets and pointe shoes in the search for greater freedom of movement."

Later in the twentieth century, as in the other arts, dance was affected by Postmodernism from the 1960s to the 1980s. While Postmodernism rejected the grand narratives [e.g. Christian ideology, Freudian psychology, political democracy etc.] and ideologies of Modernism, it was similar to Modernism in that it also rejected Enlightenment ideas and was thus another form of Romanticism. With Postmodernism, the politicisation of dance or the use of dance as a form of collective resistance to capitalism and imperialism, became a more remote prospect as "the postmodern dance movement rapidly developed to embrace the ideas of postmodernism, which rely on chance, self-referentiality, irony, and fragmentation." For example, Postmodern dance incorporated "improvisation, spontaneous determination, and chance", cast non-trained dancers, and changed the relationship of dance to the tempo of accompanying music. Later it became more conceptual and abstract while distancing "itself from expressive elements such as music, lighting, costumes, and props."

As Postmodern dance distanced itself from the masses, popular dances in the form of novelty and fad dances went to the other extreme, regularly spreading among the people like wildfires that soon burnt themselves out. They took different forms: solo dances, partner dances, group dances and freestyle dances. From 1909 to the mid 1940s there was: The Grizzly Bear, Charleston, Duckwalk, Carioca, Suzie Q, The Lambeth Walk, Thunder Clap, Conga, and the Hokey cokey. During the 1950s there was Bomba, The Chicken, Bunny Hop, The Hop, The Meatstick, Madison, The Stroll, and Hully Gully. The 1960s had Shimmy, Twist, The Chicken Walk, The Gravy ("On My Mashed Potato"), The Loco-Motion, Martian Hop, Mashed Potato, The Monster Mash, The Swim, Watusi, Chicken Dance, Hitch hike, Monkey, The Frug, Jerk, The Freddie, Limbo, Batusi, and The Shake.

In the 1970s it was Sprinkler, Penguin, Hustle, Time Warp, Bump, Tragedy, Grinding, Car Wash, Electric Slide, Robot, The Running Man, Y.M.C.A., and Little Apple. The 1980s saw Moonwalk, Cotton-Eyed Joe, Harlem Shake, Agadoo (aka Agadou), Superman (aka Gioca Jouer), The Safety, Lambada, Thriller, The Hunch, Wig Wam Bam, Cabbage Patch, Da Butt. In the 1990s there was The Carlton, Locomía, Boot Scootin' Boogie, Do the Bartman, Hammer, The Humpty, Vogue, The Urkel, Achy Breaky Heart (Line dance), Macarena, Saturday Night, Tic, Tic Tac, Thizzle, La Bomba (not to be confused with Bomba), The Roger Rabbit, and Tootsee Roll.

As can be seen from the quantity cited and the regularity of change there is no end to Modernism's ability to move with the markets or keep up with the constantly changing mass consumer pop music scene. A few styles of dance had periods of mass popularity and are still going today as social dances encouraged by regular classes in, for example, jive, salsa, and ballroom dancing.

Cinema also aided the popularity of dance in the twentieth century as can be seen in films featuring ballet in the 1940s (The Red Shoes), tap dancing in the 1950s (Singin' in the Rain), modern dance in the 1960s (West Side Story), disco in the 1970s (Saturday Night Fever), club/performance partner dancing in the 1980s (Dirty Dancing), tango in the 2000s (Chicago) and modern dance theatre in the 2010s (Pina). The global popularity of Hollywood musicals and Bollywood song-and-dance sequences have made dance an important element to be considered in any new film musical.

American dancer, choreographer, and director Jerome Robbins (1918 - 1998) (in white) demonstrates a dance move to American actor George Chakiris (left, foreground) during the filming of 'West Side Story,' directed by Robbins and Robert Wise, New York, New York, 1961.

In terms of live performance the Irish stage show, Riverdance, featuring Irish step-dancing, opened in Dublin in 1995. It went on to perform in over 450 venues worldwide and has "been seen by over 25 million people, making it one of the most successful dance productions in the world." The show also incorporated international dance elements of flamenco and tap dancing.

Thus the twentieth century has seen an explosion in interest in dance in general, and in the quantity of styles and techniques. It also has seen the overt politicisation of dance in nationalist and socialist struggles, and as an art form as affected by Romanticist and Enlightenment ideas as every other major art form.

The 21st century and new debates

Dance

has become even more prevalent in the 21st century with the internet

and global satellite media, for example, through apps like TikTok and

dance shows on TV. Riverdance is still touring and ballet is as popular

as ever. Novelty and fad dances still come and go. Social dancing and

traditional dance are still in demand due to classes, competitions and

people's natural love of dance as a form of socialising.

However, it could be asked if popular dance has simply become a form of social catharsis, and performance dance as escapism and diversion? Is there a role for dance in progressive culture? The negative reaction to Diversity's 'I Can't Breathe' radical narrative may have been simply an overreaction in a society unused to seeing dance used in a critical setting. The connection between dance and story has become relevant again as Modernist and Postmodernist aesthetic strategies have waned in popularity. 21st century ballet has seen discussion revolving around narrative or story ballet (has plot and characters), as Alastair Macaulay writes: "Nowhere more than in narrative has ballet become the land of low expectations. Audiences regularly sit through a poverty of dance-narrative expression that they would never tolerate in a movie, a novel, an opera, a play or even a musical."

Hanna Rubin discusses issues relating to choreography:

"Choreographing story ballets that will appeal to contemporary audiences presents unique challenges even for experienced dancemakers. A too-literal approach or too-traditional staging can seem quaint or flat. And what makes a suitable narrative for those coming of age in a digital era, where there are no strictures on what can be searched, seen and shared? How can a story ballet hold audiences' attention? If mere distraction becomes the goal, how can a ballet achieve the resonance that will give it continued life?"

However, choreographer Helen Pickett notes that "[n]ew stories are being created from other people's histories". She points out that traditional ballerina roles haven't always been empowering ones. "Putting the female on the pedestal was a way to say she is untouchable, but not in an elevated way — in a way that she is perhaps suffering [...] There was a lot of that in the Romantic era: Giselle goes nuts for her love."

In her own work, Pickett has featured strong female characters, and has worked on an adaptation of Arthur Miller's The Crucible for the Scottish Ballet. This is certainly an interesting direction as The Crucible was a "dramatized and partially fictionalized story of the Salem witch trials that took place in the Massachusetts Bay Colony during 1692–93. Miller wrote the play as an allegory for McCarthyism, when the United States government persecuted people accused of being communists."

Yet, although laudable, progressive narratives of resistance can also be cheapened. According to Macaulay: "'Spartacus,' the Bolshoi Ballet’s biggest hit of the last half-century, reduces its freedom-fighting story to the dimensions of trash (irresistible and sensational trash in the right performance), as enjoyable as “Flash Gordon” and scarcely more serious."

Finding the right balance between form and progressive content in ballet may be one of the biggest challenges of the 21st century for many reasons: conservative owners/backers/critics, the negative effects of Modernism and Postmodernism on form and ideology, and the lingering effects of Romanticist over-emphasis on emotion and the individual rather than on context and sociopolitical struggles.

Similarly with other forms of dance. The synthesis of the new with the old can make for exciting and engaging art (like 'I Can't Breathe') when it is based on the stories of people's actual lived lives.

While Diversity have the luxury of prime time television and a mass audience to present their views and choreographies, other choreographers work on their stories in more difficult situations, as Veronica Jiao writes:

"There are countless choreographers who have dedicated their entire body of work to the story-telling of blackness in America (Kyle Abraham, Camille Brown, Okwui Okpokwasili and the collaborators/choreographers of Urban Bush Women, to name a few). There are the nameless choreographers working four part-time jobs in order to share their stories and experiences in a downtown factory-turned-studio-turned-theatre."

Dance has truly taken its place as a significant global cultural movement. While there are still social divisions in dance today, as in the past, the difference is that the performance dances of the elites have the potential to be radical and progressive, just as the group dances of the masses today can be self-absorbed and escapist.

The future of participative dance will also depend on the level of engagement of people in sociopolitical struggle. In the past, in Ireland, for example, people flocked to traditional dance as it tied in with their nationalist and socialist beliefs. It was a way of connecting their past to a perceived or hoped for future. Similarly, in sport the Irish people flocked to Gaelic games while the previous mass support for cricket dropped dramatically as cricket was perceived to be a 'British' sport. People seek what gives their life meaning as they become more politicised, and this leads to pride in their own radical culture and radical history as a form of resistance. Participative dance will no doubt change again on this more conscious basis because it is an important part of people's social and cultural lives.

Conclusion

Dance

has had a long journey through human history. It has always been

associated with people's celebrations and festivities as a collective

expression of human emotions. However, over time particular dances

became more and more associated with different classes and groups as

societies grew ever more complex. During the time of the Enlightenment,

dance became a focus of research and criticism. Performance dance became

imbued with Classical ideals and participative dance was seen in a new

way as an important part of the heritage of all the people, and not

backward or even inferior as in the past. Later, such dances took on

even more powerful roles with revolutionary content and state folk

ensembles. However, Romanticist ideas turned dance in on itself,

shearing it of sociopolitical ideals and progressive content. That is,

until Diversity hit the stage with a performance which may yet prove to

be the beginning of a new chapter in the history of dance.

Notes:

[1]

Vicki Spencer, In Defense of Herder on Cultural Diversity and Interaction, The Review of Politics , Winter, 2007, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Winter, 2007), pp. 79-105 Published by: Cambridge University Press for the University of Notre Dame du lac on behalf of Review of Politics

[2] David Denby, Herder: culture, anthropology and the Enlightenment, HISTORY OF THE HUMAN SCIENCES Vol. 18 No. 1

© 2005 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) pp. 55–76

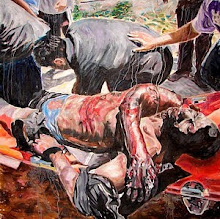

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork

consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well

as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing

based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of

Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed

country by country here. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization.