The political aspect of the 1937 Bunreacht na hÉireann or Constitution of Ireland is usually avoided in analytical writings on the constitution and emphasis tends to be on the social teaching of the church. This essay sets out to explore the language used in the 1937 Constitution to demonstrate the fundamentally political nature of the underlying philosophy of the Constitution.

While the 1937 Bunreacht na hÉireann recognised the Church of Ireland, the Presbyterian Church, the Methodist Church, the Society of Friends, the Jewish congregations and other religious congregations,[1] Article 44, 1. 2° declared that the state “recognises the special position of the Holy Catholic Apostolic and Roman Church as the Guardian of the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens”.[2] The “special position” of the church was evidenced by the predominantly Catholic influence and teachings on moral issues such as divorce, contraception and abortion influenced by the Rerum Novarum and the updated Quadragesimo Anno.

[On 5 January, 1973, the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution Act, 1972 removed from the Constitution the special position of the Catholic Church and the recognition of other named religious denominations.]

The Church’s more active position on sexual morality contrasted with its lack of concern for families affected by emigration, mental disease, terrible family living conditions and “a demoralised working class, urban as well as rural.” As Lee points out:

[On 5 January, 1973, the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution Act, 1972 removed from the Constitution the special position of the Catholic Church and the recognition of other named religious denominations.]

The Church’s more active position on sexual morality contrasted with its lack of concern for families affected by emigration, mental disease, terrible family living conditions and “a demoralised working class, urban as well as rural.” As Lee points out:

"Few voices were raised in protest. The clergy, strong farmers in cassocks, largely voiced the concern of their most influential constituents, whose values they instinctively shared and universalised as “Christian”. The sanctity of property, the unflinching materialism of farmer calculations, the defence of professional status, depended on continuing high emigration and high celibacy. The church did not invent these values. But it did baptise them.”[3]

Catholic ideas on social movements and private property had originated in the Rerum Novarum (The Condition of Labour), an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII in 1891 and were eventually to influence the content of the new constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann, published in 1937. According to J. H. Whyte in Church and State in Modern Ireland 1923-1979, the Rerum Novarum was “a cautious document” but ruled out “some extreme courses”.[4] It asserted man’s right to private property in opposition to socialism while, at the same time, asserting the right of the state to intervene in the worst excesses of individualism such as exploitative working conditions. The statements regarding private property were defined along Lockean lines.

In the Rerum Novarum it is claimed that “when man thus spends the industry of his mind and the strength of his body in procuring the fruits of nature, by that act he makes his own that portion of nature’s field which he cultivates ... it cannot but be just that he should posses that portion as his own, and should have a right to keep it without molestation.”[5]

The influence of Locke’s defence of bourgeois property in the Second Treatise of Government (c.1680) can be observed in the similar arguments he put forward on private property: “Whatsoever then he removes out of the state that nature had provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property.”[6] These ideas can be seen in Article 43, 1. 1° of the Constitution which states: “The State acknowledges that man, in virtue of his rational being, has the natural right, antecedent to positive law, to the private ownership of external goods.”[7] However, the encyclical, Rerum Novarum, was written about 210 years after Locke’s Treatises and did not reflect the profound changes in society caused by the industrial revolution. As Russell notes:

"The principle that a man has a right to the produce of his own labour is useless in an industrial civilisation. Suppose you are employed in one operation in the manufacture of Ford cars, how is anyone to estimate what proportion of the total output is due to your labour? ... Such considerations have led those who wish to prevent the exploitation of labour to abandon the principle of the right to your own produce in favour of more socialistic methods of organizing production and distribution."[8]

Yet, the Rerum Novarum states that “... it is clear that the main tenet of Socialism, the community of goods, must be utterly rejected” on the basis that, inter alia, “it would be contrary to the natural rights of mankind”.[9] Bunreacht na hÉireann (1937) Article 43, 1. 2° states: “The State accordingly guarantees to pass no law attempting to abolish the right of private ownership or the general right to transfer, bequeath, and inherit property.”[10]

Pope Leo XIII states that “God has granted the earth to mankind in general”[11] and Locke similarly claims that “... God, as King David says (Psalms 115:16) ‘has given the earth to the children of men’, given it to mankind in common.”[12] The contradiction implied in holding up the right to private property while claiming that the earth had been given to “mankind in common” left the Church open to criticism and which Pius XI endeavoured to deal with in the Quadragesimo Anno (Reconstructing the Social Order) published in May 1931. The main purpose of the Quadragesimo Anno was to update the ideas contained in the Rerum Novarum. In regard to private property, Lyons comments that “the over-riding concern was not to balance nineteenth century individualism against twentieth century collectivism, but rather to accord closely with Catholic teaching on the subject at that period.”[13]

Pius XI writes: “there are some who falsely and unjustly accuse the Supreme Pontiff and the Church as upholding both then and now, the wealthier classes against the proletariat”.[14] The product of surplus labour regarded by Marx as “wealth” and the capitalist as “profit” is described by Pius XI as “superfluous income” i.e. “that portion of his income which he does not need in order to live as becomes his station” and its use for “the grave obligations of charity” is insisted upon by the “Holy Scripture and the Fathers of the Church.”[15] Pius XI opposes the principle “that all products and profits ... belong by every right to the working man” and advocates in its place a “just wage” or a partnership of workers and executives.[16]

Bunreacht na hÉireann (1937) Article 45, 3. 2° states: “The State shall endeavour to secure that private enterprise shall be so conducted as to ensure reasonable efficiency in the production and distribution of goods and as to protect the public against unjust exploitation.”[17] A wage should be sufficient for the workingman to be able to support himself and his family as “[m]others should especially devote their energies to the home and the things connected with it.”[18] Bunreacht na hÉireann (1937) Article 41, 2. 1° states: “In particular, the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved.” Article 41, 2. 2° states: “The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.”

The Pope advocates a “reconstruction of the social order”. It was the duty of the State “to get rid of conflict between “classes” with divergent interests, and to foster and promote harmony between the various “ranks” or groupings of society.”[19] Bunreacht na hÉireann (1937) Article 45, 2. ii. states: “That the ownership and control of the material resources of the community may be so distributed amongst private individuals and the various classes as best to subserve the common good.”[20] The Quadragesimo Anno document proposed, as an alternative to class conflict, “that the members of each industry or profession be organised in “vocational groups” or “corporations”, in which employers and workers would collaborate to further their common interests.”[21] The encyclical tried to find a middle ground between the vagaries of laissez faire capitalism on the one hand and the spread of socialist ideology on the other.

In 1933 Cumann na nGaedheal joined with the Blueshirts and the new Centre Party (formed out of the old Farmers” Party) to form the United Ireland party or Fine Gael with O’Duffy as leader and Cosgrave as parliamentary leader.[22] Of the three main political parties Fine Gael was the first to take on board the vocational ideology of the Quadragesimo Anno. Whyte notes that the main exponents of vocationalist ideology were two academics, Professor Michael Tierney of UCD and Professor James Hogan of UCC and General O’Duffy. While the establishment of agricultural and industrial corporations was written into Fine Gael’s programme, interest in the idea waned. After O’Duffy’s resignation in 1934 Fine Gael’s parliamentary opposition moved away from a state corporate order, even in the economic sphere.[23]

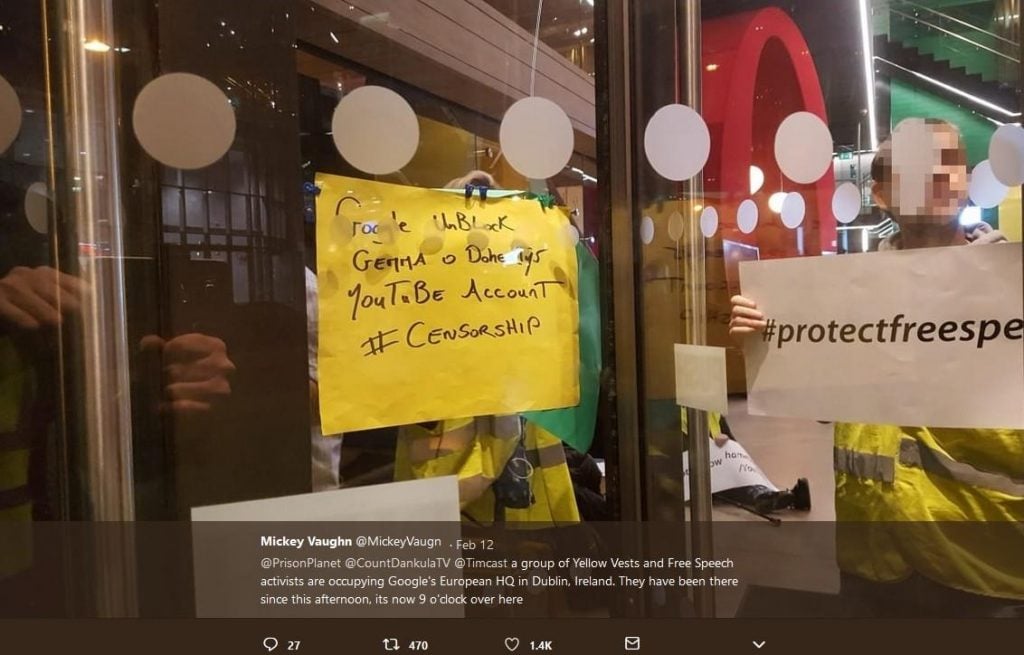

The Fianna Fáil government established a commission in 1939 to examine the “practicability of developing functional or vocational organisation” in Ireland under the chairmanship of Dr Browne, the Bishop of Galway. Even the Labour Party came under pressure of the Church’s social teaching as fundamental tenets of socialist ideology, such as the concept of a “Workers’ Republic” and public ownership, came under attack. In an amended constitution of 1940 the phrase “Workers’ Republic” was substituted with “a Republican form of government”, and the assertion regarding public ownership was rephrased as follows: “The Labour Party believes in a system of government which, while recognising the rights of private property, shall ensure that, where the common good requires, essential industries and services shall be brought under public ownership with democratic control.”[24] Thus, the Catholic Church became the catalyst for the homogenisation of mainstream Irish political ideology.

In December 1930 Pius XI published the Casti Connubii (Christian Marriage), a document also containing many of the ideas and principles later to be seen in the Irish Constitution. Issues such as birth control, abortion and divorce are dealt with in no uncertain terms. In a section on birth control, Pius XI asserts that:

“... consideration is due to the offspring, which many have the boldness to call the disagreeable burden of matrimony and which they say is to be carefully avoided by married people not through virtuous continence ... but by frustrating the marriage act. Some justify this criminal abuse on the ground that they are weary of children and wish to gratify their desires without their consequent burden.”[25]

In dealing with the abortion issue Pius XI appeals directly to the lawmakers of the land with threats of vengeance on those who ignore the Church’s teaching: “If the public magistrates not only do not defend them, but by their laws and by their ordinances betray them to death at the hands of doctors or of others, let them remember that God is the Judge and Avenger of innocent blood which cries from earth to heaven.”[26]

[On 7 October, 1983, the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution Act, 1983 acknowledged the right to life of the unborn, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother]

[On 18 September, 2018, the Thirty-sixth Amendment of the Constitution Act 2018 provided for the regulation of termination of pregnancy]

[On 18 September, 2018, the Thirty-sixth Amendment of the Constitution Act 2018 provided for the regulation of termination of pregnancy]

Divorce is denounced as one of the evils of “Communism”. Pius XI writes: “what an amount of good is involved in the absolute indissolubility of wedlock and what a train of evils follows upon divorce”[27]. Divorce is yet another example of “the unheard of degradation of the family in those lands where Communism reigns unchecked.”[28] Bunreacht na hÉireann (1937) Article 41, 3. 2° states: “No law shall be enacted providing for the grant of a dissolution of marriage.”[29]

[On 17 June, 1996, the Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution Act, 1995 provided for the dissolution of marriage in certain specified circumstances.]

[On 17 June, 1996, the Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution Act, 1995 provided for the dissolution of marriage in certain specified circumstances.]

The political aspect of the Church’s thinking culminated with the Divini Redemptoris (Atheistic Communism) published on the nineteenth of March 1937, three months before Bunreacht na hÉireann was “enacted by the People”[30] on the 1st of July. The introduction describes the history of “Previous Condemnations” of “Communism” as early as 1846 when Pius IX described it as “absolutely contrary to the natural law itself” in Syllabus. The role of the Church is described as a “special” mission to defend truth and justice (the word “special” also describes the position of the Catholic Church in Ireland in the Constitution).[31] The Encyclical endeavours to explain communist theory and practice as essentially a “false messianic idea” and a “pseudo-ideal of justice and equality” which traps the multitudes with a “deceptive mysticism” and rejects, as a basic principle, “any link that binds woman to the family and the home”.[32]

The spread of Communism is attributed to the “real abuses chargeable to the liberalistic economic order” which has left workmen in “religious and moral destitution”.[33] In contrast, the Church restates the socio-economic ideas of the Quadragesimo Anno and calls on the parish priests to win “back the laboring masses”.[34] This was to be achieved through “the militant leaders of Catholic Action” whose object was “to spread the Kingdom of Jesus Christ” (e.g. An Rioghacht in Ireland) and would be trained through study circles, conferences and lecture courses before taking “direct action in the field”.[35] In the penultimate section of the encyclical entitled “Duties of the Christian State” the Church calls on States to recognise “the authority of the Divine Majesty”[36] (Article 44, 1, 1° of the Constitution asserts that: “The State acknowledges the homage of public worship is due to Almighty God.”) and insists that the State allows the Church full liberty to fulfil her divine and spiritual mission”.[37]

While it may be argued that the 1937 Constitution merely reflected the views and aspirations of a predominantly Catholic population or even, as Lyons contends, helped de Valera “steer between the Scylla of republicanism and the Charybdis of dominionism”,[38] however, the “invisible hand” of the Church steered state ideology into the safer waters of a Pax Hibernia for some decades to come.

Notes:

[1] Bunreacht na hÉireann [1937] (BÁC: Foilseachán Rialtas, n.d.) 144. Article 44, 1. 3° states: “The State also recognises the Church of Ireland, the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, the Methodist Church in Ireland, the Religious Society of Friends in Ireland, as well as the Jewish Congregations and the other religious denominations existing in Ireland at the date of the coming into operation of this Constitution.”

[2] Bunreacht 144.

[3] Joseph Lee, Ireland 1912-1985 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991) 159.

[4] J. H. Whyte, Church and State in Modern Ireland 1923-1979. 2nd ed. (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan Ltd., 1980) 63.

[5] William J. Gibbons, Seven Great Encyclicals (New York: Paulist Press, 1963) 4.

[6] John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (London: J. M. Dent, 1993) 128.

[7] Bunreacht 142.

[8] Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy (London: Counterpoint, 1984) 612-3.

[9] Gibbons 7.

[10] Bunreacht 142.

[11] Gibbons 4.

[12] Locke 127.

[13] F.S.L.Lyons, Ireland Since the Famine (Great Britain: Fontana, 1974) 546.

[14] Gibbons 136-7.

[15] Gibbons 139.

[16] Gibbons 144.

[17] Bunreacht 150.

[18] Gibbons 145.

[19] Gibbons 148.

[20] Bunreacht 148.

[21] Whyte 67.

[22] Lee 179.

[23] Whyte 80-1. See also Lyons 528.

[24] Whyte 83-4. See also Lyons 525.

[25] Gibbons 92.

[26] Gibbons 96.

[27] Gibbons 104.

[28] Gibbons 105.

[29] Bunreacht 138.

[30] Bunreacht, iii.

[31] Gibbons 178.

[32] Gibbons 180-1.

[33] Gibbons 182-3.

[34] Gibbons 200.

[35] Gibbons 201.

[36] Gibbons 204.

[37] Gibbons 205.

[38] Lyons 521.