Contains

spoilers

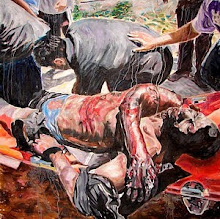

In mainstream culture, social and political violence by the poor depicted in cinema is generally situated in narratives that try to maintain the legitimacy of the state. Consequently it also tries to delegitimize violence that may threaten the state. For example, the recent Mexican-French film New Order (2020) depicts the street violence and demonstrations of the poor as mindless violence, murder, and robbery, rather than as an inevitable reaction to decades of extreme poverty and oppression.

In these

scenarios, the indigent, the poor, the working class, have no rational program,

no ideological agenda, and no democratic future where they could be in the

driving seat of economic and cultural progress. They are forever condemned to

explosive, cathartic and senseless cyclical violence that is then simply stage-managed

by the state through its courts, police, army and prisons. It could be argued

that the main reason for these depictions of the poor is that mainstream

culture is itself one of the tools used in the maintenance of that status quo.

Arracht Trailer on youtube.com

https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Two

recent Irish films, Arracht (‘Monster’)

(2019) and Herself (2020),

depict violence in very different eras. Arracht

is based in Connemara in the middle of the nineteenth century, while Herself is set in a modern urban setting

in Dublin. On another level, both films show how violence is allowed to be depicted in mainstream

cinema.

Arracht, for example, is a

well made film with much work gone into the authenticity of the depiction of

the potato blight and the subsequent desperation of the local inhabitants. The

narrative centres on Colmán

Sharkey who lives on the Atlantic coast with his wife and young son. Colmán has

taken on Patsy Kelly as a farmhand and fisherman, a dodgy character who was in the

Royal Navy. The landlord has raised the rents and Colmán decides to talk to him

personally, bringing Patsy with him. However,

“At the landlord's estate, Colmán unsuccessfully tries to persuade him not to raise rents due to the famine devastating the country. Patsy wanders off where he encounters the two collection agents and the landlord's daughter. He murders all three before being discovered by Colmán, who is shocked by what he finds and notices a frightened young girl has witnessed the scene. Patsy kills the landlord, leading to a confrontation with the Sharkey brothers in which Sean [Colmán’s brother] is fatally stabbed. Enraged, Colmán brutally beats Patsy and leaves him for dead.”

Soon these murders enter local nationalist folk culture in the form of a ballad sung by local fishermen. It is assumed that Colmán killed the landlord and he is seen as an heroic resistance fighter. However, it was shown that Colmán is not a violent person from an earlier scene when Patsy disarms an armed man sent to collect the rents, and Colmán orders Patsy to return the gun.

We know that

the violence in the landlord's house was committed by Patsy and not Colmán. In this case it is the actions of a sociopath (Patsy) which

are immortalized in culture despite Colmán’s non-violent approach to resistance. There is a sleight

of hand here that shows radical nationalist culture as illegitimate violence

carried out by sociopaths and furthermore depicts the singers of the ballad as

being ignorant of the facts of the situation, and that they are glorifying deeds

that are basically portrayed as terrorism.

Given the

severity of colonial oppression in Ireland in the nineteenth century, violence

against the landlords or representatives of the state is unsurprising.

Resistance by the peasants is delegitimized and limited to the legal and courts

system, which is upholding the landlord rent increases and evictions that are

exacerbating the conflict in the first place.

A similar

cinematic sticking point over legitimate and illegitimate violence occurs in Neil

Jordan’s film Michael Collins set

during the Irish War of Independence. Jordan has the IRA explode a car bomb

even though car bombs were not used until much later during the Troubles. Some

critics focused in on this event as legitimating the later IRA campaign which they

saw simply as modern terrorism unlike the earlier struggle for independence.

In Herself, the contemporary story of a

woman (Sandra) fighting back against her violent ex-husband in the courts

system, is a more positive narrative in that it shows her struggle against the

structural violence of state bureaucracy. Furthermore, her tenacity in also resisting

criminal violence by her ex-husband works well on both literal and symbolic

levels.

While her

battle against domestic violence is an uphill struggle against the prejudices

of the state court system she eventually wins custody of her children. Her

decision to build her own house in the back garden of the wealthy doctor she

works for is an interesting twist in that her desire to be free and independent

is determined by middle class power and control. However, her determination to

create something for herself is significant as the learning processes involved

in building a house counters modern consumerist ideology with the practical

knowledge of production.

Furthermore, Sandra

organizes a team to help her build the house, working for free, which harks back

to an old Irish social tradition of a meitheal

(where neighbours would come together to assist in the saving of crops or other

tasks).

Unfortunately,

the finished house is then burned down by her ex-husband in a criminal act of

revenge. Yet this does not deter her (or her friends) from starting afresh. Thus

the film carries a positive message that one can win out through struggle within

the system, but also symbolically without the system, with the collective help

of others despite enormous setbacks and challenges.

Herself Official Trailer

on

youtube.com

https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Despite the

fact that the legitimacy of the state is maintained in Herself (winning custody of her children through the courts, her husband

being caught and put away for years), the message of struggle, learning, and

co-operation towards a common goal is quite subversive. She learns not only how

to fight the system but also how to construct a new way of being within the

system which has profound possibilities for the future (learning new skills,

working collectively, solidarity, etc.).

A similar

situation can be seen in The Wind that

Shakes the Barley (2006), a film by Ken Loach set during the Irish War of

Independence (1919–1921) and the Irish Civil War (1922–1923), wherein the First

Dáil sets up a parallel court system to the

colonial institutions, which not only became accepted and recognized by the local

people (de facto) but were eventually

to become de jure with the setting up

of the new Irish state.

However, whether the message is conservative (Arracht) or progressive (Herself), it is usually oblique, as overtly radical content rarely gets screened. Cinema is an extremely costly business, and screenplay and finished film decisions are made by wealthy and conservative producers. Yet, every now and then films depicting working class life and struggles are produced which are significant, for example, Salt of the Earth (1954), The Organizer (1963) (Italian), The Battle of Algiers (1966)(Italian-Algerian), Blue Collar (1978) (USA), Norma Rae (1979) (USA), Vera Drake (2004) (UK), I, Daniel Blake (2016) (UK).

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country here.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization.