Introduction

What is the future for architecture in these times of climate change and economic crises? Should sustainability and affordability be a major factor in the design and development of future buildings? What about aesthetics? There are many individual examples of modern buildings today that have positive aesthetic qualities, but can major future problems, like climate change, be resolved by individual efforts? Or will it take the role of the state with grand visions for the future? While architecture may not seem to be an important issue compared with unemployment or poverty, it is one of the most important of the arts in terms of longevity, function and expense. And its meaning can go beyond mere buildings to symbolism of the state and national values.

The question of aesthetics is complex as modern architectural design is “caught between the diminished architecture of the 99% and the austere architecture of the 1%”, while at the same time architecture is pulled between popular opinion of what is good design and elite views that often contradict.

It is also well know that the production of cement is polluting. Therefore, many architectural projects now emphasize sustainability, like housing schemes to be built from cross-laminated timber and powered by renewable energy, bricks made of recycled construction waste, schemes that will be carbon neutral and function off-grid, plans for the world’s first wooden football stadium, and other housing schemes that will be made from sustainably harvested local wood and save 100s of megatons of carbon in the process.

However, no matter how sustainable these projects are, there is no escaping the aesthetic values of design which will ultimately sustain the building into eternity or see it eventually blown up to the smiles of hordes of ill-wishers.

So why is design so important for something which is ultimately functional? Is it because we have to look at these buildings for a very long time once they are constructed? How do we decide what is beautiful and why?

The whole history of architecture is riddled with controversies. Often what is considered beautiful now was criticized during its own time. Buildings have been knocked down and blown up in many different kinds of situations. Indeed, some have even been rebuilt exactly as before under controversial circumstances or post-war.

Today the debate still goes on about aesthetics and architecture with functional styles overtaking decorative styles only to be overtaken by decorative styles again. What determines these changes? Do political and economic systems play an important role in the kind of aesthetics which become preeminent? And if so, why? Did socio-political-economic systems such as hierarchical feudalism, industrialized capitalism, or state socialism play important roles? Does Neo-liberalism today? How relevant have the opinions of the users and builders of these edifices been?

Maybe more than all the other arts, architecture has been highly affected by the conflict between Enlightenment and Romantic ideas ever since the Italian architect and designer Brunelleschi visited Rome to study the ancient ruins of classical Roman architecture in 1432. The Romantic reaction to Neoclassical architecture materialized later in the form of Neo-Gothic architecture from the 1740s onwards.

Renaissance architecture

The rise of the bourgeoisie in the form of the Medicis in Italy guided a major change in architecture from the Romanesque and Gothic styles of earlier times to the new Renaissance designs based on ancient Greek and Roman architecture. The earlier medieval styles had been largely used by feudal kings, and bishops of the powerful Catholic church for their castles and cathedrals. Gothic had grown organically out of Romanesque designs over time, for example, the small roof on medieval belfries became taller and thinner until it was eventually incorporated into the belfry as a Gothic spire.

The revival of Classical learning in Rome went along with Renaissance humanism and the development of science and engineering. It is interesting to note that Brunelleschi’s first architectural commission was the Ospedale degli Innocenti (1419–c. 1445), or Foundling Hospital, designed as a home for orphans. His next project was the Basilica of San Lorenzo the location of the tombs of the Medici family who sponsored the church – rather than castles or cathedrals.

Brunelleschi, in the building of the dome of Florence Cathedral (Italy) in the early 15th century (1296-1436), not only transformed the building and the city, but also the role and status of the architect.

The study of the ancient ruins in Italy (Rome and Pompeii) and Greece (Athens) led to a clearer understanding of the difference between Greek and Roman architecture and subsequently to consciously Greek, Roman and Greco-Roman hybrids of Neoclassical design.

This knowledge was expressed in the Renaissance style, a style which was consciously brought to fruition through learning and a desire to revive the ideas of the ‘Golden Age’. The humanistic learning of the time set forth a positive conception of man (in opposition to the ‘fallen man’ of the established church) and was seen in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (7 CE), where he describes the lost Golden Age as a time in which nature and reason were aligned and produced naturally good men:

“The Golden Age was first; when Man, yet new,This view reflected the new learning that man could have an optimistic view of the future and control nature to create a better life for all. In Renaissance architecture, “symmetry, proportion, geometry and the regularity of parts”, would reflect a more dignified mode of existence combined with concepts of equality, citizenship and republican organization of society. Renaissance architecture depicted “orderly arrangements of columns, pilasters [rectangular columns] and lintels [horizontal supports], as well as the use of semicircular arches, hemispherical domes, niches [shallow recesses] and aediculae [small shrines] replaced the more complex proportional systems and irregular profiles of medieval buildings.”

No rule but uncorrupted Reason knew:

And, with a native bent, did good pursue.

Unforc’d by punishment, un-aw’d by fear.”

Palais des études of the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1830

By the mid eighteenth century Renaissance architecture developed into full blown Neoclassicism and became an international style as it was adopted by progressive circles in other countries particularly for the design of public buildings. The Neoclassical style incorporated many decorations such as mascarons [symbolic faces], cartouches [oval or oblong designs], festoons [wreaths or garlands], corbels, various leaves and branches, rustications [contrasting textures], trophies, horns of abundance, lion heads and female faces or from other applied arts. An important form of Neoclassicism was the Beaux-Arts architecture which originated in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, particularly from the 1830s to the end of the 19th century. It was very popular in the United States from 1885 to 1920, and its very last, large public projects included the Lincoln Memorial (1922), the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. (1937), and the American Museum of Natural History’s Roosevelt Memorial (1936).

The most important aspect of Beaux Arts architecture, aside from its study of Greek or Roman models, was its sculptural decorations which (aside from its balustrades, pilasters, festoons, and cartouches) included “statuary, sculpture (bas-relief panels, figural sculptures, sculptural groups), murals, mosaics, and other artwork, all coordinated in theme to assert the identity of the building.”Neoclassicism also influenced city planning as “the grid system of streets, a central forum with city services, two main slightly wider boulevards, and the occasional diagonal street were characteristic of the very logical and orderly Roman design” as well as highlighting important public buildings.

The growing secularism and the rise of evangelicalism in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries did not go unnoticed by philosophical movements associated with Catholicism and high church or Anglo-Catholic beliefs. The influence of Romanticist medievalism and anti-industrialism could be seen in the Gothic Revival that began in the late 1740s in England. Figures like the conservative architect, Augustus Pugin, believed that Christian values were being destroyed by Classicism and industrialization. These reactionary ideas took on political connotations:

“with the “rational” and “radical” Neoclassical style being seen as associated with republicanism and liberalism (as evidenced by its use in the United States and to a lesser extent in Republican France), the more spiritual and traditional Gothic Revival became associated with monarchism and conservatism, which was reflected by the choice of styles for the rebuilt government centres of the UK Parliament’s Palace of Westminster in London, the Canadian Parliament Buildings in Ottawa, and the Hungarian Parliament Building.”However, by the beginning of the twentieth century the “academic refinement of historical styles” was beginning to be perceived as the architecture of a declining aristocratic order. The move away from Gothic decoration could be seen in the Modernist architects favouring of functional details over historical references. Their designs exhibited and revealed functional and structural elements such as steel beams and concrete surfaces.

Modernist architecture

As Romanticism changed into Modernism, the Romantic interest in the medieval and feudal craft form of production changed into its opposite as formalism and an anti-human aesthetic took its place instead. Modernism, in its dismissal of tradition, rejected classical notions of form in art (harmony, symmetry, and order) and, like Romanticism, rejected the ‘certainty’ of Enlightenment thinking. Modernism emphasized form over political content and rejected the ideology of Realism and Enlightenment thinking on liberty and progress.

The Bauhaus school building in Dessau, Germany, 1919

“The Bauhaus style of architecture featured rigid angles of glass, masonry and steel, together creating patterns and resulting in buildings that some historians characterize as looking as if no human had a hand in their creation. These austere aesthetics favored function and mass production, and were influential in the worldwide redesign of everyday buildings that did not hint at any class structure or hierarchy.”The Bauhaus style (also known as the International Style) was consciously cosmopolitan in its ahistorical designs and principles of mass production. Many Germans of the time had been influenced by the cultural experimentation that was happening in the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution, particularly Constructivism which had originated in Russia beginning in 1913.

Constructivist architecture

Constructivism was a form of Modernist architecture that developed in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and early 1930s. It emerged out of broader art movements movements such as Futurism and Suprematism. Russian Futurism was a movement of Russian poets and artists who rejected the past and celebrated “machinery, violence, youth, industry, destruction of academies, museums, and urbanism”. These ideas were based on Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s (Italian poet, editor, art theorist) Futurist Manifesto, which was written and published in 1909.

Marinetti wrote:“We want to glorify war – the only cure for the world – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill”, and later, in 1919, co-wrote the Fascist Manifesto with Alceste De Ambris. Suprematism was “characterised by basic geometric forms, such as circles, squares, lines and rectangles, painted in a limited range of colours”.

Thus we can see that Constructivism grew out of the highly individualistic, anti-historical, nihilistic, pared-down forms of Modernist art, typical of Romantic ideas.

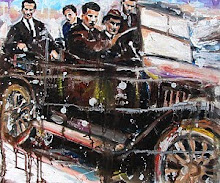

Intourist Garage by Konstantin Melnikov, 1933

The move away from Constructivist pared-down forms and back to decoration and craft could already be seen in Europe and America with the introduction of Art Deco influences from the mid-1920s. Art Deco buildings featured a lot of surface decoration around windows and doors, and especially around the tops of skyscrapers. This decoration was done in low relief and combined many geometric patterns and figures.

Thus the move to Classicism was not surprising as criticism of Modernist austerity took hold. The major projects of the time, skyscrapers, the Moscow Metro and apartment blocks, were all designed with Classical features that included much art and craft elements. These included sculpture, friezes, mosaics, molding, stucco, carved wooden panels, frescoes, bass relief, and carved wooden panels. After the death of Stalin the ‘luxurious’ style of Socialist Classicism was replaced by Khrushchyovka, the name given to a type of low-cost, concrete-paneled Modernist building style supervised by Nikita Khrushchev.

The central

square. Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, Moscow, 1935

(Vystavka Dostizheniy Narodnogo Khozyaystva, abbreviated as VDNKh or VDNH)

(Vystavka Dostizheniy Narodnogo Khozyaystva, abbreviated as VDNKh or VDNH)

By the late 1960s Modernism was falling out of favour in the West with many Modernist apartment blocks being eventually blown up. The harsh lines of Modernist architecture did not age well and something more artistic was in demand. The austerity, formality, and lack of variety in Modernist architecture was generally criticized for having no relation to architectural history, street plans, or the culture of individual cities. This also led to the re-introduction of craft and historical design elements into a new architectural philosophy called Postmodernism.

Postmodernist architecture

Unfortunately, Postmodernism, a late 20th-century movement characterized by broad skepticism, subjectivism, relativism, irreverence and parody, and a general suspicion of reason, was not not too different from the subjectivism, relativism and general suspicion of reason in Romanticist and Modernist ideas. Postmodernist architects approached architecture with eclectic non-contextualized ideas resulting in diverse aesthetics, colliding styles, and form for its own sake producing some very self-indulgent designs. Asymmetric forms were one of the trademarks of Postmodernism as large buildings were broken into different structures and forms, ‘Camp’ humor was used on the basis that something could appear so bad that it was good, and the theatricality of absurd and exaggerated forms were common. As a style Postmodernist architecture has been criticized as vulgar and populist.

The Dancing House, Prague, Czech Republic, 1996

Neoliberal architecture

The influence of free market Neoliberalism on architecture globally has been critiqued by Douglas Spencer as “refashioning human subjects into the compliant figures – student-entrepreneurs, citizen-consumers and team-workers – requisite to the universal implementation of a form of existence devoted to market imperatives.” Spencer believes that the architecture of neoliberalism “serves mechanisms of control and compliance while promoting itself, at the same time, as progressive.” It does this through the social processes these “buildings enforce – displacement of the poor, privatisation of public space, the decimation of social housing.”

Reflections at Keppel Bay apartment complex in Keppel Bay, Singapore by Daniel Libeskind (2011)

“Each enclosure required an Act of Parliament, and the aristocrats who controlled both Houses of Parliament ruthlessly used their legislative power to enrich themselves, while thrusting agricultural labourers down to the verge of starvation.” [1]

Sustainable architecture

Other forces were concerned with the negative aspects of untrammeled capitalism and the environment. The desire to bring architecture in line with other ‘green’ movements since the late 1980s has led to the concept of sustainable architecture:

“Sustainable architecture designs and constructs buildings in order to limit their environmental impact, with the objectives of achieving energy efficiency, positive impacts on health, comfort and improved liveability for inhabitants; all of this can be achieved through the implementation of appropriate technologies within the building [and] making the space and materials employed completely reusable.”Indeed in the United States “a vast ecosystem of green commerce has grown” up around sustainable architecture “spurring sales in products ranging from solar panels to low-VOC paints and low-flow toilets. “Green building is now a $1 trillion global industry,””

Beddington Zero Energy Development (BedZED) is an environmentally friendly housing development in Hackbridge, London, England 2000–2002.

BedZED is in the London Borough of Sutton, 2 miles (3 km) north-east of

the town of Sutton itself. Designed to create zero carbon emissions, it

was the first large scale community to do so. The distinctive roofscape has solar panels and passive ventilation chimneys.

However, this still leaves the problem of aesthetics, as the Neoliberal designs are highly individualistic architectural enterprises generally in post-modern states which do not have, or desire to have, ultimate control of the ownership or design of such projects.It is the public realm where the state does have the most control, despite Neoliberal desire to reduce it to nothing. The public realm generally refers to “those areas of a town or city to which the public has access. It includes streets, footpaths, parks, squares, bridges and public buildings and facilities.”

The public realm is a contested realm where aesthetics are lauded or criticised according to the inclination of the state or the desires of the public but at least broader integrated planning designs can be implemented, unlike Neoliberal ideology which “maintains that ‘the market’ delivers benefits that could never be achieved by planning.” Neoliberalism also “sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations [and] redefines citizens as consumers.”

Such ideology tries to naturalise the logic of capitalism by redefining people in its own image. However, it also reflects the power of elites and their political and economic grip on society as a whole. Styles of art and architecture in society also reflect elite hegemony. This can be seen in the very expensive apartments of luxury condominium towers (designed by ‘starchitects’) that have very little relationship with their urban neighbourhoods.

It can be seen in the designs of skyscrapers for expensive hotels or headquarters of multinational companies. Contemporary designs for concert halls and art museums have had their praisers but also critics of some overwrought designs such as architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff’s comment on the Denver Art Museum that: “In a building of canted walls and asymmetrical rooms—tortured geometries generated purely by formal considerations — it is virtually impossible to enjoy the art.” Frank Gehry’s business school building at the University of Technology Sydney has been described as “a creased building […] which resembles a “squashed brown paper bag”.

Like the earlier Modernist designs of the Bauhaus, contemporary architectural design can be austere and alienating (or in some cases just asinine) reflecting the confidence and egoism of wealthy elites. It also reflects the economics of our time as the wealthy get to decide the individualistic designs of their residences, work places and entertainment centres much like the aristocracy of the eighteenth century.

Conclusion

It has been suggested that the world’s most popular architect is Antoni Gaudí (if measured by ticket sales for the Sagrada Família in Barcelona). As Edwin Heathcote notes, “It is not an accident that Gaudí is also the most obsessively decorative architect of modernity.” Ornament and decoration in architecture has been a popular aesthetic throughout the centuries. Heathcote also writes:

“Ornament is not essential to architecture but people continue to like it. Perhaps architects need to begin thinking why, after their best efforts to educate them otherwise, they still do. Perhaps the people are right and it is indispensable.”Is it because people appreciate ornament, reflecting their love of applied arts and crafts, and respect for the skills that go into making them? We must not forget that decorative arts form an important part of national museum exhibitions around the world. As with any art it can be hard to understand what is popular and why, and what is considered alienating or ‘human’ in architecture. But it does seem that the Greeks and Romans hit on something in their combinations of art and architecture that has struck a chord with many people over time. As Rebecca Solnit writes:

“Italian cities have long been held up as ideals, not least by New Yorkers and Londoners enthralled by the ways their architecture gives beauty and meaning to everyday acts.” (Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking)

Notes

[1] Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy (Unwin, London, 1984) p 611

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork

consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well

as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing

based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of

Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed

country by country here. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization.