Talk given at Dublin City University's Centre for Consumption Studies Workshops - 'Finding an Irish Voice: Reflections upon Celtic Consumer Society and Social Change' on 17 October 2007

It is very difficult, if not impossible, to analyse one’s own work. Yet, at the very least it can help one define what one is doing or trying to do and thus help in the creative process itself. In my case the art takes the form of oil painting on stretched canvas. It is a strange way to spend the day – the work is physical yet determined by an intellectual and emotional driving force.

Painting is like cooking in that one spends a long time preparing something which is then consumed in a short period of time. A meal is planned, prepared and cooked over a period of time and then eaten in minutes. A painting is planned, drawn, and then painted over a long period of time and then in an exhibition is observed for some minutes until the spectator moves on to the next painting. So is it true to say that art is consumed in a matter of minutes? The effects of food on our body lasts many hours after consumption, the affect of art on our conscience and sub-conscience can also be long lasting. Images can burn themselves on our minds in ways that we can never forget.

My interests and therefore my subject matter have for the main been centred on Ireland and Irish history and politics. In Ireland group identity has been focused on individuals with Nationalist or Republican ideals for social and political change in Ireland. As an artist I have always been interested in how art can contribute to change. Our past history of colonialism has given us the ability to identify with the poor and oppressed around the world. But how does art work help in this process? Can the art of the local have a universal appeal? If so, why? Do the pictures I make consciously or unconsciously represent Ireland and the Irish people? If I analyse the form and content of my paintings can I see the Ireland of today? Or do they just represent what I perceive only? Am I creating art or documenting what is going on around me, or both? Is this basically what artists have done over the centuries anyway?

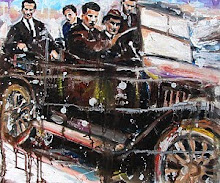

It is easy to identify with visual images. We recognise portraits of the 1916 leaders and identify with our radical past, the people who made our country what it is today. I started becoming interested in political art after a couple of years studying for a BA in Fine Art in the National College of Art and Design in Dublin. In identity terms I identified with people who were trying to change the social and political regime in Ireland. Initially, I made art about unemployment, repressive legislation, neo-colonialism etc. However it is a very negative life when you are always against something. I decided to deal with the social and political by offering positive images of what could be done by portraying people 'producing' rather than 'consuming' [e.g. playing music, doing traditional dance, demonstrating etc] empathizing with the positive aspect of Irish identity, strengthening it by re-affirming it through art. After a hiatus of some years reading for a MA and a PhD, I returned to art and worked on historical images of Irish life and radical political leaders going back 400 years. But I felt that this was becoming very limited as I was using secondary sources, that is, images from historical and travel books. I wanted to work in such a way that I could use primary sources, to take control of the source of the images. At the same time it struck me that politics was all around me and I just had to go and find it.

I went into Dublin city with my camera and looked around. I noticed contrasts between the historical statues and their surroundings. I noticed Brinks vans coming out of shopping streets as shoppers went in. I saw the new Asian, African, and Russian shops on Moore Street which had been the domain of Irish working class street sellers. I took many photos and worked on a new series of paintings which I called 'Dublin: A City of Contrasts'.

The aim of this series is threefold:

1 To depict Dublin as it is in this moment in time, recording current states, trends and aspects that we take for granted but can change tomorrow.

2 To examine particular contrasts that have emerged due to current levels of wealth and immigration.

3 To represent aspects that symbolize positive developments for the future of Dublin and all of its inhabitants.

I noticed that the statues of historical figures such as Jim Larkin, Daniel O’Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell, and James Connolly look down on a new city that sits uncomfortably with their varieties of nationalism and socialism. These symbols of the past, standing in silent judgment of the follies of the present, act as control rods in the current economic fission reminding its old and new, wealthy and poor citizens alike of past struggles and hardships. I realized I could combine these historical symbols with modern symbols to create interesting contrasts. Soon after, I looked for any other symbolic contrasts that I could find while walking around the city. I also sought out events or aspects that could be symbolic of a future, more people and eco friendly Dublin.

These paintings in the Dublin cityscapes series have formal qualities. They are figurative. In terms of tone, there is high contrast. In terms of colour, they are very bright, often primary colours in the main. In terms of composition they are snapshots of a particular moment and place in time. In a way they offer a window onto Dublin today. Every element of the composition contains parts of Irish identity today – old buildings [symbols of the historic city/nation], new expensive cars [symbolic of the economic system], people of different ethnic backgrounds [symbols of modern multicultural Ireland], buses and trains [symbols of our state transport system]. Stylistically the paintings are expressionist in movement and feeling yet impressionist in terms of the fall of light on people and objects. As they are based on snapshots they show the constant movement of the city.

The snapshot structure of the compositions is not a stable structure – people and cars move quickly in and out of the frame. The ephemeral is made permanent. The movement reflects a fast-paced, complex life. A Spanish friend looking at the paintings thought people seem to be running in Dublin compared to slower life in Spanish cities. In my case this is partly as a result of the changeover from camera film to digital photography. When you know you have only 24 or 36 shots in a roll of film you are careful about what you shoot. The scenes one photographs become carefully structured and thus one tends to project future paintings. With digital photography now I can take around 750 shots in the space of a few hours. I can take pictures without even bothering to look at what I am photographing. I can carry the camera very low and push the button with my thumb instead of my index finger. This allows for photographs with a totally different structure. If the camera is angled up from below then people loom large in the structure of the composition.

Photography allows for instantaneous coincidences of objects and people to be captured which may never happen again. Short term events can be seen from different angles. A quick glance at a nice car, a suddenly emptied table, a flash of sunlight, a particular car or person of ethnic background changing a traditional context, an organized event or demonstration or a temporary shadow on a street can all be captured consciously or, in blind-snapping mode, can be captured unconsciously with a digital camera when one doesn’t have to think twice about the limited shots left such as when one is using a roll of film. I also find that, every time I go into the city to take photographs, my ideas of what I am looking for in the photograph have changed. Initially I was looking for quite obvious contrasts and I find now this has evolved to more subtle differences in composition, content and colour.

In a way this represents the nature and complexity of society today. Historically compositions in art were highly organized, for example, showing the aristocratic paterfamilias surrounded by his land, family and dog. It was a stable life and everyone knew their place. Today’s society however can be represented in its rapidly ever-changing forms through photographic snapshots that capture its essence in one thousand of a second. However, it is important to stress that photography for the artist is a kind of note-taking, giving the artist a basic structure to work with in terms of colour, tone and shapes. After that, the artistic process takes over as one decides on the qualities of line, tone, colour and texture to use to make an interesting painting that will stand up in its own right as a painting because of its density or intensity of brushstrokes and colours, pencil lines or thick palette-knife painting or because of its conflicting or merging tones and colours. In that way the painting comes to exist at a far remove from a flat naturalistic photograph. Whether I change the structure and content of a snapshot image has become a bigger question for me now. In the past I have altered or added in elements if I felt it would clarify the meaning of the symbolism and content of the painting. I find myself less and less willing to intervene now. Maybe that is where the subtleties come in.

In a way though photos are like watching a film with the sound turned off. It can be very difficult to follow the narrative of a film purely by watching the movements of the actors in and out of different scenes. This is why titles on a painting can be like the sound being suddenly turned up. The titles given to paintings may appear to be superfluous to the visual, emotional aspect of art. Yet it is always interesting to look at the relationship between text and image. They operate like the Hegelian idea of thesis and antithesis producing a synthesis, a new meaning. It is an effect used very commonly in advertising to give a certain mood to a product rather than showing the product directly. Yet titles can have a profound affect on how we understand a particular painting. Titles can make the real seem abstract [in the sense of adding a mythological symbolism to a real scene] or they can make the abstract seem real [by explaining in words the relationship between two objects inhabiting the same frame]. They can add a new dimension to the meaning of a painting.

Titles may clarify art especially in this case where one could argue that there seems to be many contradictions: evening light nostalgia yet in cold colours, very bright light for an often cloudy city, a snapshot as a permanent painting, arbitrary framing yet chosen for its arbitrariness. All this shows the subjective nature of art, even with art that has pretensions to objectivity.

I felt that the bright light that I was using was a kind of Greek light, as I regularly go to Greece on holiday. I like the strong light of the Mediterranean. Yet it was pointed out to me that the light was very Irish. The sharp light and pale blue sky was more reminiscent of the Irish light than the warmer Greek light. Does this show that we cannot escape our identity? As a child of mixed identity myself, and Irish father and an Austro-Hungarian mother, I often wondered if this has this made me more interested than most in exploring Irishness than many Irish people [I am very interested in Irish music, dance and language].

Despite my family background I empathise more with Mediterranean culture than Germanic culture. Yet my Irish side seems to come out when I least expect it. Maybe there are aspects of my personality which are Germanic which have yet to be pointed out to me of which I am not aware. I was brought up as an Irish child [despite living in the USA till I was six] yet was not aware of difference until recently. I discovered that it was relatively unusual for a person of my generation to have been fed Austrian foods, such as salami, dumplings, Austrian cakes and biscuits; world cuisine dishes such as moussaka, curry, Chinese spare ribs, as well as the Irish meat and 2 veg. There was the cosmopolitan element too. My father worked for Aer Lingus which meant ease of travel as a child for visiting my relatives in America, Austria and England during a time when it was not taken for granted like it is today. I suppose that’s how we often discover difference - when it is pointed out to us.

So the cosmopolitan element – is that important? The awareness of the relationship between the local and the global comes from travel to different continents. To appreciate the local, what we have, after seeing what others have, or have not, as the case may be. To say this is what we have - some of which is very good, some of which is very bad. Some things which others will aspire to, others things they will hope to avoid. Is what I show in a painting a document of what is or just my interpretation of what is?

While I am taking photos am I documenting or interpreting? I feel that I am doing both at the same time. I am documenting in the sense that the image is a representation of a real event yet I am also interpreting in that what I choose to photograph [particular objects and places in time; particular conjunctions of objects] is highly selective. How do I separate out the two? Can I ever have control of the content? If a painting includes the latest Mercedes car as a symbol of Ireland’s burgeoning wealth, how do I know that a potential buyer is interested in buying the painting because it represents his/her world outlook? How does the viewer know if I, the artist, might have included it as a type of criticism? Maybe I am not being critical but delighted with this New Ireland. Does that mean that ultimately I can only reflect what is out there and with the passing of time the image can be seen in its true context? That is, viewed completely differently from a presumably much different Irish society of the future. More and more I feel that I can only represent what is out there.

Everything I represent is a symbol of the now which will resonate differently with different people. Yet maybe the fact of its representation makes its existence inescapable - which is itself a form of political statement. That expensive car did exist, and it could only exist because of a particular socio/political situation pertaining in that society at that particular time.

Yet a striving for authenticity is also an important goal. To represent moments in Irish time, in Irish life as they were in that split-second. While Joyce was writing Ulysses, he said to a friend, “I want to give a picture of Dublin so complete that if the city one day suddenly disappeared from the Earth, it could be reconstructed out of my book.” Joyce wanted Ulysses to serve as a kind of blueprint of life in Dublin in 1904. I like the idea of showing multifaceted aspects of Irish life today frozen in time for the future. To make art based on something I know and have easy access to. They are collectively a document and an interpretation at the same time. Not the usual nicely framed and structured buildings of art directed at tourists but a look at ourselves when we are least aware of it. Maybe for others that is a revelation. Seeing how the Irish live, the cosmopolitan nature of their society, the historic buildings, the new cars and cafes.

For the Irish, an examination of what is there now but may be gone tomorrow when the painting itself becomes a piece of history, like all art of the past showing us the way we were, for good and for bad. Authenticity was important to Vincent Van Gogh who once wrote in a letter to his brother regarding criticisms of his peasant paintings that ‘anyone who prefers to have his peasants looking namby-pamby had best suit himself. Personally I am convinced that in the long run one gets better results from painting them in all their coarseness than from introducing a conventional sweetness.’

Many artists objectify internal feelings [e.g. the Clown and Maggie Man (Gleas magaidh) paintings of J.B. Yeats as metaphors exploring feelings of isolation and alienation which in turn influenced Samuel Beckett]. One can also work the other way round, subjectifying external reality through one’s use of colour, tone, brushwork and impasto.

However, art is not about pre-existing styles that simply need to be applied to new situations. Paul Gauguin wrote to a friend: “A word of advice: don't paint too much direct from nature. Art is an abstraction, derive this abstraction from nature while dreaming before it, and think more of the creation that will result.” This is an important statement, I feel, as a work of art is above all still a work of art and not a slice of reality. All art is abstract and has its rules about what we feel works aesthetically or not. Pure naturalism may be impressive but may also be boring as a work of art. Understanding how paint works in terms of shape, colour, and tone is a long slow procedure that is an essential aspect of the developing creative process itself. The form and style arise out of an examination of content and are constantly changing over time, sometimes so imperceptibly that even the artist does not notice that all has changed.

In another interesting quote about the nature of art, Stephen Westfall has noted: “Painting and art have never had the same agenda. Art is a much newer argument than painting. Painting has been around for 25,000 years. Painting is commemorative. Art, on the other hand, is a kind of discourse that in a funny way seeks to do away with itself.” The truth of this statement can be seen in the change of attitude towards painting with the invention of photography. It was considered unnecessary for art to record anymore and therefore photography was elevated to an art at the expense of painting. The documentary aspect of art was over-emphasized to the detriment of the creative aspect of the craft of painting. This was a strange sleight of hand like saying that we didn’t need to learn how to write anymore as a typewriter could do it for us. It led the way for art that could be purely abstract and about form instead of content. Art was given an almost mystical status produced by the genius artistic mind and separated from any association with mere craft. Yet oddly enough, the separation of art from representing life and instead representing itself actually returned art back to a pure craft. Intricate modern formalist and abstract design is as highly skilled and time-consuming as any craft but like any pure craft does not make any social or political interventions into the nature of human society.

It is in these two senses - photography for documentation and abstraction in painting craft - that we can see how art seems to be ‘doing away with itself’. I believe that figurative art is very fundamentally social and political in what it chooses to represent and also in what it chooses to ignore. Artists can choose to intervene in the world around them as they have done many times in the past. Art can comment upon or simply bear witness to events and forces but it also has the power to touch the emotions and intellect at the same time and the directness and power of such work can be transformative.

Michael Cronin has stated elsewhere, ‘it is easy to become despondent in the context of the brutal authoritarianism of the market and the criminalization of dissent’, and that ‘solidarity still matters’. In that sense identity matters, who we identify with within our own group and who in turn identifies with us. If there is any such thing as a distinctly Irish voice let it be that Irish artists would be easily recognised by their readiness to debate with the world through their art. Moreover, by developing a global awareness of others we also constantly re-evaluate our view of ourselves.