Trees are a very important part

of world culture and have been at the centre of ideological conflict for hundreds

of years. Over this time they have taken the form of Sacred trees, Christmas

trees and New Year trees. In the current debates over climate change, trees

have an immensely important role to play on material and symbolical levels both

now and in the future. With the rising awareness of climate change, climate

resilience i.e. the ability to recover from or adjust

easily to misfortune or change, has become the focus of groups from

local community action to global treaties. The planting of trees is an important

action that everyone from the local to the global can engage in. Trees act as

carbon stores and carbon sinks, and on a cultural level they have been used to

represent nature itself the world over.

As symbols, trees have been imbued with different meanings over time

and I suggest here that they should continue to hold that central role as a prime

symbol of our respect for nature, and not just at Christmas time but the whole

year round in the form of a central community tree for adults and children alike.

In an uncertain future, the absolute necessity of developing a society that

harks back to much earlier forms of engagement with nature in a sustainable way

will have to have a focal point. Trees as important symbols of our respect for

nature have a long and elemental past.

The Tree of Life

From earliest times trees have had a profound effect on the human psyche:

“Human beings, observing the growth and death of trees, and the annual

death and revival of their foliage, have often seen them as powerful symbols of

growth, death and rebirth. Evergreen trees, which largely stay green throughout

these cycles, are sometimes considered symbols of the eternal, immortality or

fertility. The image of the Tree of life or world tree occurs in many

mythologies.”

In Norse mythology the tree Yggdrasil, “with

its branches reaching up into the sky, and roots deep into the earth, can be

seen to dwell in three worlds - a link between heaven, the earth, and the

underworld, uniting above and below. This great tree acts as an Axis mundi,

supporting or holding up the cosmos, and providing a link between the heavens,

earth and underworld.”

Yggdrasil, the World Ash (Norse)

Sacred Trees

However, both Christianity and Islam treated the worship of trees as

idolatry and this led to sacred trees being destroyed in Europe and most of

West Asia. An early representation of the ideological conflict between paganism

(polytheistic beliefs) and Christianity (resulting in the cutting down of a

sacred tree) can be seen in the manuscript illumination (illustration) of Saint

Stephan of Perm

cutting down a birch tree sacred to the Komi people as part of his

proselytizing among them in the years after 1383.

Stefan of Perm takes an axe to a birch hung with pelts and cloths that is sacred to the Komi of Great Perm (a medieval Komi state in what is now the Perm Krai of the Russian Federation.)

Christian missionaries targeted sacred groves and sacred trees during

the Christianization of the Germanic peoples. According to the 8th century Vita

Bonifatii auctore Willibaldi, the Anglo-Saxon missionary Saint Boniface and his

retinue cut down Donar's

Oak (a sacred tree of the Germanic pagans) earlier the same century and then

used the wood to build a church.

"Bonifacius" (1905) by Emil Doepler.

Christmas Trees

Over time the pagan

world tree became christened as a Christmas tree. It was believed that evil

influences were warded off by fir or spruce branches and “between December 25

and January 6, when evil spirits were feared most, green branches were hung,

candles lit – and all these things were used as a means of defense. Later on,

the trees themselves were used for

the same purpose; and candles were hung on them. The church retained these old

customs, and gave them a new meaning as a symbol of Christ.’(p20) While there

are records of this practice dating from 1604 of a decorated fir tree in

Strasbourg, it was in Germany that the Christmas tree took hold in the early

19th century. It then

“became popular among the nobility and spread to royal courts as far as

Russia.”

Father and son with their dog

collecting a tree in the forest, painting by Franz Krüger (1797–1857)

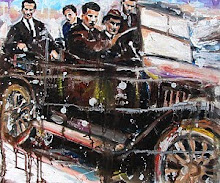

The Russian Revolution

In Russia the tradition of installing and decorating a Yolka (tr: spruce tree) for Christmas was very popular but fell into disfavor (as a tradition originating in Germany - Russia's enemy during World War I) and was subsequently banned by the Synod in 1916. After the Russian Revolution in 1917 Christmas celebrations and other religious holidays were prohibited under the Marxist-Leninist policy of state atheism in the Soviet Union.

In Russia the tradition of installing and decorating a Yolka (tr: spruce tree) for Christmas was very popular but fell into disfavor (as a tradition originating in Germany - Russia's enemy during World War I) and was subsequently banned by the Synod in 1916. After the Russian Revolution in 1917 Christmas celebrations and other religious holidays were prohibited under the Marxist-Leninist policy of state atheism in the Soviet Union.

A 1931 edition of the Soviet magazine Bezbozhnik, distributed by the League of Militant Atheists, depicting an Orthodox Christian priest being forbidden to cut down a tree for Christmas

New Year's trees

Although the Christmas tree was banned people continued the tradition

with New Year trees

which eventually gained acceptance in 1935: “The New Year tree was encouraged

in the USSR after the famous letter by Pavel Postyshev, published in Pravda on

28 December 1935, in which he asked for trees to be installed in schools,

children's homes, Young Pioneer Palaces, children's clubs, children's theaters

and cinemas.” They remain an essential part of the Russian New Year traditions when Grandfather

Frost, like Santa Claus, brings presents for children to put under the tree or

to distribute them directly to the children on New Year's morning performances.

Trees in public places

In many public places around the world Christmas trees are displayed

prominently since the early 20th century. The lighting up of the tree has

become a public event signaling the beginning of the Christmas season. This is

now usual even in small towns whereby a large fir is chopped down and displayed

prominently in a central part of the town or village. While fir trees are now

grown expressly for sale and display, in the past the cutting down of whole

trees (maien or meyen) was forbidden:

“Because of the pagan origin, and the depletion of the forest, there were

numerous regulations that forbid, or put restrictions on, the cutting down of

fir greens throughout the Christmas season.”(p20)

Not cutting down trees

However if we look

at the origins of sacred trees the important point

was that they were not to be cut down, as respect for nature took

precedence. The

cutting down and destruction of so many trees today has become an

important

part in the commercialization of Christmas. However, growing a tree in

the centre of

villages, towns and cities as the focal point of our relationship with

nature could be a year round celebration for adults and children and

another aspect of the call for climate resilience policies

the world over. The tree could then be decorated at Christmas or New

Year. The

decorations can be removed from the tree afterwards, allowing it to

become a

focal point for other festivities throughout the year. The educational

value of

this strategy for children would also be as an object lesson in the

importance of

sustainability and conservation.

Celebrating

nature by chopping down the

material reality of nature in the form of a tree every year is a

contradiction in terms and could be remedied by encouraging people to

grow trees or buying potted fir

trees instead. Our ancestors from all over the world knew the importance

of the balance of nature and tried to keep that balance through rites

and prayers before the sacred trees. Now, in an era of climate change,

rapidly becoming climate chaos, it is incumbent on us more than ever to

develop a new appreciation and respect for nature and especially for

trees as a primary symbol of that relationship.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an

Irish artist who has exhibited widely around Ireland. His work consists of

paintings based on cityscapes of Dublin, Irish history and geopolitical themes.

His critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a

database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed

country by country on his blog.

No comments:

Post a Comment