Mike Davis Planet of Slums [1]

Slumdog Millionaire

The highly successful film Slumdog Millionaire (2008) directed by Danny Boyle is a story of Jamal Malik, a young man from the Juhu slums of Mumbai who appears on the Indian version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? (Kaun Banega Crorepati in the Hindi version) and exceeds people's expectations, thereby arousing the suspicions of the game show host and of law enforcement officials. His motive for appearing on the show is to attract the attention of Latika, a girl he has fallen in love with and who he originally met as a child after the Bombay Riots. [2]

It is a film that appears to put money above all and individual striving as the basis of progress. Yet, even in a time when the dominance of neo liberal ideology is so strong that it has become naturalised, there is still room for an oppositional perspective to shine through cracks in the corrugated iron. This will be argued through an examination of the character Jamal Malik's behaviour as he faces up to the police, Indian elites and crime lords as the narrative unfolds.

Probably one of the most important and revealing scenes in the film is on the show when he is asked by the host Prem Kumar the penultimate question that could win him 10 million rupees. The question is ‘Which cricketer has scored the most first class centuries in history?’ and Prem Kumar warns him: ‘If you answer wrong, you lose everything (clicks his fingers) just like this.’ But then they have to take a break. During the interval Prem Kumar talks over his shoulder to Jamal from the bathroom:

Prem Kumar: A guy from the slums becomes a millionaire one night. You know who is the only other person who has done that? Me. I know what it feels like. I know what you have been through.

Jamal Malik: I am not going to become a millionaire. I don’t know the answer.

Prem Kumar: You said that before, yeah?

Jamal Malik: No, really this time I don’t.

Prem Kumar: Come on, you can’t take the money and run now. You are on the edge of history, kid. Maybe it is written my friend. I don’t know - I’ve got a gut feeling you are going to win this. Trust me, Jamal. You are going to win. [3]

He leaves and when Jamal goes to the bathroom he see the letter B written in the steam on the mirror.

They return to the show.

On the show [4]

Jamal chooses to use his life line and two wrong answers are taken away leaving B and D. Jamal stares at Prem and then chooses D. Prem has a slightly shocked look on his face and badgers him to choose B. But Jamal refuses to budge:

Prem Kumar: B: Ricky Ponting or D: Jack Hobbs?

Jamal Malik: D.

Prem Kumar: Not B? The Ricky Ponting, the Australian great cricketer?

Jamal Malik: D. Jack Hobbs.

Prem Kumar: You know?

Jamal Malik: (Shakes his head)

Prem Kumar: So it could be B: Ricky Ponting?

Jamal Malik: Or it could be D: Jack Hobbs! The final answer D. [5]

The correct answer turns out to be D. In the clapping and uproar Prem Kumar smiles and does a little dance calling (Do the dance! Come on!) and beckoning Jamal to him who refuses and stays in his chair. Jamal stares at him and when asked if he is ready for the final question he looks uncomfortable but then responds sarcastically, ‘But maybe it is written, no?’ Jamal's slum upbringing has taught him never to trust those in power.

The show ends before they have time to do the final question. As Jamal leaves Prem escorts him to the back door where he is grabbed by the police and taken off in a police van. One of the studio managers comes over to Prem when he hears the commotion:

Manager: What's going on?

Prem Kumar: He's a cheat.

Manager: How do you know he's cheating?

Prem Kumar: (Speaks Hindi). I fed him the wrong answer, and he never should call it right.

Manager: You gave him an answer?

Prem Kumar: Not exactly. Well that doesn't matter. That's my show! [6]

In the police station [7]

Prem’s use of charm one minute and aggression the next shows us that his route to the top has not been particularly virtuous. He has achieved wealth and fame and now feels securely part of the class that he had aspired to become a member of. This has allowed him to take on the superior attitudes towards his former slum dweller compatriots that are the mark of a confident class. Prem plays up to the chic audience from the opening lines of the show:

Prem Kumar: [starting lines] So Jamal, tell me something about yourself.

Jamal Malik: I work in a call centre in Juhu.

Prem Kumar: Phone basher! And what type of call centre would that be?

Jamal Malik: XL5 mobile phones.

Prem Kumar: Ohh... so you're the one who calls me up every single day of my life with special offers?

Jamal Malik: Actually I'm an assistant.

Prem Kumar: An assistant phone basher? And what does an assistant phone basher do exactly?

Jamal Malik: I get tea for people and...

Prem Kumar: Chaiwalah! Well ladies and gentlemen, Jamal Malik, garma garam chai dene walah from Mumbai, lets play Who Wants To Be A Millionaire! [8]

Prem has learned the language of the well-to-do who look down on the socially aspirant that managed to get trendy jobs (‘phone bashers’) with a foreign multinational but then seizes with delight on the opportunity to use the word ‘chaiwalah’ (teaboy) which he is all too familiar with from his own lowly past.

This kind of mocking treatment only gets worse in the police station when he is tortured to force him to ‘reveal’ how he is doing so well answering the questions in the show.

So, were you wired up?

A little electricity will loosen his tongue, give him.

Yes sir.

So, were you wired up?

Mobile phone or a pager?

Or coughing accomplice in the audience? [9]

The bias of the police against the poor is evident in their lack of belief in the possibility that he might be telling the truth.

The fact that, in the film, Jamal can be held overnight in a police station while at the same time being the subject of intense media attention says a lot about the power of the police and the censorship of the media. It implies that any kind of opposition to the state can be effectively dealt with by the ‘security forces’ without any fear of public knowledge of what is happening to those arrested.

Survival strategies

So what are the possibilities of opposition for those ignored or exploited by the system? This not a film about political struggle [unlike The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006) (The Irish War of Independence), Pan's Labyrinth (2006) (The Spanish Civil War), Che: Part One (2008) (The Cuban Revolution), or The Army of Crime (The French Resistance) (2009) to name some examples].

It is a film about personal struggle. What are the survival strategies for the poor?

In Prem’s case it has been a combination of charm and deceit. Jamal refuses to use the same strategies. Jamal knows that the pursuit of money for its own sake is not the path to happiness.

He resists the symbols of authority and oppression: the police (he refuses to give in to the police to end the torture), the wealthy developers (he gives them no respect), the wealthy who many would like to emulate (he disbelieves Prem’s ‘clue’), tourists (seen as fair game), the use of traditional lore (‘it is written’), child kidnappers (rescues Latika with his brother). He sails past the Scylla of rival crime lords and the Charybdis of the biased state to achieve his goals. This is the most important lesson of the film despite the criticisms by many critics of the neo-liberal ideology contained within the film. One such example:

At the end of the film, Jamal is permanently absolved of his disease-like impoverishment. He accomplishes this by winning millions of dollars as a successful contestant in (what should theoretically be) a chance-based game show. Amazingly, Jamal is able to correctly answer each question by employing his accumulated life experiences and, in a sense, locating the answers ‘within himself.’ The fact that Jamal is pre-configured for success as a contestant on “who wants to be a millionaire” speaks volumes about the sort of subversive ideology embedded in what otherwise seems like a fairly ‘inspiring’ narrative. [10]

While it is true that Jamal locates the answers ‘within himself’ many of the answers derive from personal tragedies in his young life. These experiences taught him not to trust anyone in a position of authority. Jamal wants to go on the show to find an old friend he is in love with while most of the ‘phone bashers’ in the office are desperately trying to get on the show to escape their own lives as technological coolies.

Jamal does not revel in his winnings. In fact, each correct answer only brings back bad memories of terror (when the slum is attacked), extreme sorrow (when his mother is killed), indignities (when he jumps into the open lavatory), horror (when he witnesses another child being blinded to increase begging income for his minders), betrayal (when his brother sleeps with the girl he loves), frustration (when he finds Latika working as a servant), torture (by the police) etc. Even on the show he is betrayed again by the host who tries to trick him out of winning (not to mention calling him a cheat and handing him over to the police to be tortured).

Getting autograph (‘Poo’ is actually a mixture of chocolate and peanut butter) [11]

Despite all the criticism of neo-liberal ideology it cannot be ignored that Jamal has learned the most important lesson about middle class hypocrisy – that for the wealthy to remain wealthy the poor must be kept poor. It is no secret that slums provide the middle classes with an enormous pool of very cheap labour for their financial investments with very few costs to the state. Here is how one business writer put it in an article about the slum Dharavi:

Dharavi enjoys relatively reliable power and water supply and an unending stream of cheap labour from rural areas under economic duress. Add to this the reluctance of government officials to intervene into the slum physically or otherwise and the central location within Mumbai’s transport hub, and one begins to understand the economic miracle of Dharavi. And miracle it is: one estimate places the annual value of goods produced in Dharavi at USD 500 million. Commercial and manufacturing enterprises provide employment for a large share of Dharavi’s population as well as for some living outside Dharavi. [12]

This fact is a constant source of embarrassment for some members of the middle classes who would prefer to see the attention shifted away to other more western conceptions of the relationship between ‘employees’ and ‘entrepreneurs’. For example, Shilpa Shetty, "a Bollywood actor who became a star in Britain after winning Celebrity Big Brother, told newspapers that she felt 'that internationally recognised films focus more on our slums and poverty'." [13]

Of course, there are individuals who focus on slums and poverty in the form of slum tourism. Jean-Paul Sartre wrote that to reveal is to change. Slum tourism reveals the positive (community spirit) and negative (dire poverty) aspects of life in the slum to well-off tourists who react in different ways to slum living conditions. However, the inhabitants of the slum also have a viewpoint which is rarely heard. In an article in The New York Times, Kennedy Odede, a resident of Kibera, one of the largest slums in Africa, writes:

Slum tourism has its advocates, who say it promotes social awareness. And it’s good money, which helps the local economy. But it’s not worth it. Slum tourism turns poverty into entertainment, something that can be momentarily experienced and then escaped from. People think they’ve really “seen” something — and then go back to their lives and leave me, my family and my community right where we were before. I was 16 when I first saw a slum tour. I was outside my 100-square-foot house washing dishes, looking at the utensils with longing because I hadn’t eaten in two days. Suddenly a white woman was taking my picture. I felt like a tiger in a cage. Before I could say anything, she had moved on.

Odede is sceptical of the long term benefits of such experience on the tourists:

To be fair, many foreigners come to the slums wanting to understand poverty, and they leave with what they believe is a better grasp of our desperately poor conditions. The expectation, among the visitors and the tour organizers, is that the experience may lead the tourists to action once they get home. But it’s just as likely that a tour will come to nothing. After all, looking at conditions like those in Kibera is overwhelming, and I imagine many visitors think that merely bearing witness to such poverty is enough. Nor do the visitors really interact with us. Aside from the occasional comment, there is no dialogue established, no conversation begun. Slum tourism is a one-way street: They get photos; we lose a piece of our dignity. [14]

However, it is possible that the issue is one of scale. The vast exposure of slum life in a film like Slumdog Millionaire could have far-reaching effects on the social, legal and political life of the Indian state. Chitra Divakaruni, a poet and professor at the University of Houston defended an article she wrote in the Los Angeles Times called ‘The Slumdog Fight’:

On NPR, she responded to Priya Rajsekar, saying that the film is not “poverty porn.” She cited Charles Dickens as an artist who, through his work, changed child labor laws in England, and that Danny Boyle follows in that tradition. [15]

It may be that such exposure can bring changes to labour laws, attitudes etc but in the end it will come down to the people living in slum conditions themselves to bring about change. If we look at the Factory Acts in England we can see that it took ‘radical agitation’ (see, for example, Richard Oastler who urged workers to use strikes and sabotage [16]) to change the labour laws:

Many children (and adults) worked 16 hour days. As early as 1802 and 1819 Factory Acts were passed to regulate the working hours of workhouse children in factories and cotton mills to 12 hours per day. These acts were largely ineffective and after radical agitation, by for example the "Short Time Committees" in 1831, a Royal Commission recommended in 1833 that children aged 11–18 should work a maximum of 12 hours per day, children aged 9–11 a maximum of eight hours, and children under the age of nine were no longer permitted to work. [17]

In the end, Jamal finds success not because of his win but mainly by defeating every middle class attempt to exploit him along the way. The final scene shows Jamal, not celebrating by drinking champagne with his new rich friends, but dancing in solidarity with ordinary people in a type of flash mob scene in a train station. To experience a flash mob of people coming together to dance a particular routine and then melt away back into the crowd is to experience a moment of identity with a group of strangers in a highly alienated modern society.

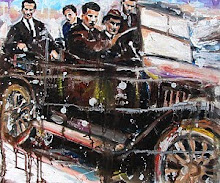

In the train station [18]

Slumdog Millionaire is not a political film (as noted above). Nor is it a film about money (as argued above). Slumdog Millionaire is a spiritual film, which also makes it subversive. That is because genuine change cannot come about by people corrupted by the state or by the love of money. Change can only come about by people who believe in an ideal that has the love of other people as its basis. Once freed from the fear of authority and the desire for material gain, solidarity in the face of oppression is a very real possibility.

Notes

[1] Mike Davis Planet of Slums (Verso, London, 2007) p.92.

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slumdog_Millionaire

[3] My transcription

[4] http://www.comicbookbin.com/slumdogmillionairereview-001.html

[5] http://www.subzin.com/quotes/Slumdog%20Millionaire/

[6] My transcription

[7] http://www.comicbookbin.com/slumdogmillionairereview-001.html

[8] http://www.subzin.com/quotes/Slumdog%20Millionaire/

[9] http://www.subzin.com/quotes/Slumdog%20Millionaire/

[10] http://maximillianeinstein.com/thehaplesscapitalist/?p=91

[11] http://www.stephandtonyinvestigate.com/?p=1863

[12] http://www.nyenrode.nl/businesstopics/europeindia/Pages/%E2%80%9CJaiHo%E2%80%9DDharavi.aspx

[13] http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2009/feb/23/india-celebrates-slumdog-millionaire-oscars-victory

[14] http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/10/opinion/10odede.html

[15] http://gaetanamoviesforallevents.blogspot.com/2009_03_23_archive.html

[16] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Oastler

[17] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Child_labour

[18] http://www.comicbookbin.com/slumdogmillionairereview-001.html

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist who has exhibited widely around Ireland. His work consists of drawings and paintings and features cityscapes of Dublin, images based on Irish history and other work with social/political themes (http://gaelart.net/). He is also developing a blog database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world. These paintings can be viewed country by country on his blog at http://gaelart.blogspot.com/.