realism

Term used with various meanings in the history and criticism of the arts. In its broadest sense the word is used as vaguely as Naturalism, implying a desire to depict things accurately and objectively.

Often, however, the term carries with it the suggestion of the rejection of conventionally beautiful subjects, or of idealization, in favour of a more down-to-earth approach, often with a stress on low life or the activities of the common man.

Richard Thomas Moynan (1856 - 1906)

Taking Measurements: the artist copying the cast of a lion from the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus in the National Gallery of Ireland 1887

In a more specific sense, the term (usually spelled with a capital R) is applied to a movement in 19th-century (particularly French) art characterized by a rebellion against the traditional historical, mythological, and religious subjects in favour of unidealized scenes of modern life. The leader of the Realist movement was Courbet, who said, ‘painting is essentially a concrete art and must be applied to real and existing things’.

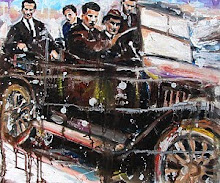

Thomas Couture (1815 - 1879) La Peinture Realiste (Realist Painting) 1865

[Mocking the Realists]

The term Social Realism has been applied to 19th- and 20th-century works that are realistic in this second sense and make overt social or political comment. It is to be distinguished from Socialist Realism, the name given to the type of art that was officially promoted in the Soviet Union and some other Communist countries; far from implying a critical approach to social questions, it involved toeing the Party line in an academic style.

Magic Realism and Superrealism are names given to two 20th-century styles in which extreme realism—in the sense of acute attention to detail—produces a markedly unrealistic overall effect. Since the 1950s the term ‘realism’ has also been used in a completely different way, describing certain types of art that eschew conventional illusionism. This usage is found mainly in the terms New Realism and Nouveau Réalisme, which have been applied to works made of materials or objects that are presented for exactly what they are and are known to be. See also Verism.

IAN CHILVERS. "realism." The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. 2003. Encyclopedia.com. 29 Mar. 2010 http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O3-realism.html

Realism

Realism in the visual arts and literature refers to the general attempt to depict subjects "in accordance with secular empirical rules," as they are considered to exist in third person objective reality, without embellishment or interpretation. As such, the approach inherently implies a belief that such reality is ontologically independent of man's conceptual schemes, linguistic practices and beliefs, and thus can be known (or knowable) to the artist, who can in turn represent this 'reality' faithfully. [...]

Realism often refers more specifically to the artistic movement, which began in France in the 1850s. These realists positioned themselves against romanticism, a genre dominating French literature and artwork in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Purporting to be undistorted by personal bias, Realism believed in the ideology of objective reality and revolted against the exaggerated emotionalism of the romantic movement. Truth and accuracy became the goals of many Realists. Many paintings which sprung up during the time of realism depicted people at work, as during the 19th century there were many open work places due to the Industrial Revolution and Commercial Revolutions.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Realism_%28arts%29

Social Realism

A very broad term for painting (or literature or other art) that comments on contemporary social, political, or economic conditions, usually from a left-wing viewpoint, in a realistic manner.

Often the term carries with it the suggestion of protest or propaganda in the interest of social reform.

However, it does not imply any particular style; Ben Shahn's caricature-like scenes on injustice and social hypocrisy in the USA, the dour working-class interiors of the Kitchen Sink School in Britain, and the declamatory political statements of Guttoso in Italy are all embraced by the term. See also Realism.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_realism

Realism and Impressionism

Photography in the nineteenth century both challenged painters to be true to nature and encouraged them to exploit aspects of the painting medium, like color, that photography lacked. This divergence away from photographic realism appears in the work of a group of artists who from 1874 to 1886 exhibited together, independently of the Salon. The leaders of the independent movement were Claude Monet, August Renoir, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, and Mary Cassatt. They became known as Impressionists because a newspaper critic thought they were painting mere sketches or impressions. The Impressionists, however, considered their works finished.

Many Impressionists painted pleasant scenes of middle class urban life, extolling the leisure time that the industrial revolution had won for middle class society. In Renoir's luminous painting Luncheon of the Boating Party, for example, young men and women eat, drink, talk, and flirt with a joy for life that is reflected in sparkling colors. The sun filtered through the orange striped awning colors everything and everyone in the party with its warm light. The diners' glances cut across a balanced and integrated composition that reproduces a very delightful scene of modem middle class life.

Since they were realists, followers of Courbet and Manet, the Impressionists set out to be "true to nature," a phrase that became their rallying cry. When Renoir and Monet went out into the countryside in search of subjects to paint, they carried their oil colors, canvas, and brushes with them so that they could stand right on the spot and record what they saw at that time. In contrast, most earlier landscape painters worked in their studio from sketches they had made outdoors.

The more an Impressionist like Monet looked, the more she or he saw. Sometimes Monet came back to the same spot at different times of day or at a different time of year to paint the same scene. In 1892 he rented a room opposite the Cathedral of Rouen in order to paint its facade over and over again. He never copied himself because the light and color always changed with the passage of time, and the variations made each painting a new creation. The differences are obvious when we compare the painting of Rouen Cathedral that is now in Switzerland with the one that is now in Washington, D.C. [Compare the two Rouen paintings in the Artchive: "Dull Weather" and "Full Sunlight"]

Realism meant to an Impressionist that the painter ought to record the most subtle sensations of reflected light. In capturing a specific kind of light, this style conveys the notion of a specific and fleeting moment of time. Impressionist painters like Monet and Renoir recorded each sensation of light with a touch of paint in a little stroke like a comma. The public back then was upset that Impressionist paintings looked like a sketch and did not have the polish and finish that more fashionable paintings had. But applying the paint in tiny strokes allowed Monet, Renoir, or Cassatt to display color sensations openly, to keep the colors unmixed and intense, and to let the viewer's eye mix the colors. The bright colors and the active participation of the viewer approximated the experience of the scintillation of natural sunlight.

The Impressionists remained realists in the sense that they remained true to their sensations of the object, although they ignored many of the old conventions for representing the object "out there." But truthfulness for the Impressionists lay in their personal and subjective sensations not in the "exact" reproduction of an object for its own sake. The objectivity of things existing outside and beyond the artist no longer mattered as much as it once did. The significance of "outside" objects became irrelevant. Concern for representing an object faded, while concern for representing the subjective grew. The focus on subjectivity intensified because artists became more concemed with the independent expression of the individual. Reality became what the individual saw. With Impressionism, the meaning of realism was transformed into subjective realism, and the subjectivity of modem art was born.

- From "Experiencing Art Around Us", by Thomas Buser

http://www.artchive.com/artchive/impressionism.html

Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement that began as a loose association of Paris-based artists whose independent exhibitions brought them to prominence in the 1870s and 1880s. The name of the movement is derived from the title of a Claude Monet work, Impression, Sunrise (Impression, soleil levant), which provoked the critic Louis Leroy to coin the term in a satiric review published in Le Charivari.

Characteristics of Impressionist paintings include visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject matter, the inclusion of movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience, and unusual visual angles. [...]

Radicals in their time, early Impressionists broke the rules of academic painting. They began by giving colours, freely brushed, primacy over line, drawing inspiration from the work of painters such as Eugène Delacroix. They also took the act of painting out of the studio and into the modern world. Previously, still lifes and portraits as well as landscapes had usually been painted indoors. The Impressionists found that they could capture the momentary and transient effects of sunlight by painting en plein air.

Painting realistic scenes of modern life, they portrayed overall visual effects instead of details. They used short "broken" brush strokes of mixed and pure unmixed colour, not smoothly blended or shaded, as was customary, in order to achieve the effect of intense colour vibration.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impressionism

Naturalism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naturalism_%28arts%29

Socialist realism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socialist_realism

'revolutionary romanticism'

Maxim Gorky discusses 'revolutionary romanticism' in 'Soviet Literature' - Speech delivered in August 1934 at the Soviet Writers’ Congress 1934.

http://marxists.org/archive/gorky-maxim/1934/soviet-literature.htm

'Revolutionary and Proletarian Literature'

Karl Radek on 'Contemporary World Literature and the Tasks of Proletarian Art' in a speech delivered in August 1934 at the Soviet Writers’ Congress 1934.

http://marxists.org/archive/radek/1934/sovietwritercongress.htm

Romanticism

Romanticism or Romantic Era is a complex artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe, and gained strength in reaction to the Industrial Revolution. In part, it was a revolt against aristocratic social and political norms of the Age of Enlightenment and a reaction against the scientific rationalisation of nature, and was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature, but had a major impact on historiography, education and natural history.

The movement validated strong emotion as an authentic source of aesthetic experience, placing new emphasis on such emotions as trepidation, horror and terror and awe—especially that which is experienced in confronting the sublimity of untamed nature and its picturesque qualities, both new aesthetic categories. It elevated folk art and ancient custom to something noble, made of spontaneity a desirable character (as in the musical impromptu), and argued for a "natural" epistemology of human activities as conditioned by nature in the form of language and customary usage.

Romanticism reached beyond the rational and Classicist ideal models to elevate a revived medievalism and elements of art and narrative perceived to be authentically medieval, in an attempt to escape the confines of population growth, urban sprawl, and industrialism, and it also attempted to embrace the exotic, unfamiliar, and distant in modes more authentic than Rococo chinoiserie, harnessing the power of the imagination to envision and to escape.

In European painting, led by a new generation of the French school, the Romantic sensibility contrasted with the neoclassicism being taught in the academies. In a revived clash between color and design, the expressiveness and mood of color, as in works of J.M.W. Turner, Francisco Goya, Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix, emphasized in the new prominence of the brushstroke and impasto the artist's free handling of paint, which tended to be repressed in neoclassicism under a self-effacing finish.

As in England with J.M.W. Turner and Samuel Palmer, Germany with Caspar David Friedrich, Norway with J.C. Dahl and Hans Gude, Spain with Francisco Goya, and France with Théodore Géricault, Eugène Delacroix, Théodore Chassériau, and others; literary Romanticism had its counterpart in the American visual arts, most especially in the exaltation of an untamed American landscape found in the paintings of the Hudson River School. Painters like Thomas Cole, Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church and others often expressed Romantic themes in their paintings. They sometimes depicted ancient ruins of the old world, such as in Fredric Edwin Church’s piece Sunrise in Syria. These works reflected the Gothic feelings of death and decay. They also show the Romantic ideal that Nature is powerful and will eventually overcome the transient creations of men. More often, they worked to distinguish themselves from their European counterparts by depicting uniquely American scenes and landscapes. This idea of an American identity in the art world is reflected in W. C. Bryant’s poem, To Cole, the Painter, Departing for Europe, where Bryant encourages Cole to remember the powerful scenes that can only be found in America. This poem also shows the tight connection that existed between the literary and visual artists of the Romantic Era.

Some American paintings promote the literary idea of the “noble savage” (Such as Albert Bierstadt’s The Rocky Mountains, Landers Peak) by portraying idealized Native Americans living in harmony with the natural world. Thomas Cole's paintings feature strong narratives as in The Voyage of Life series painted in the early 1840s that depict man trying to survive amidst an awesome and immense nature, from the cradle to the grave.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romanticism

Romantic realism

Romantic realism is an aesthetic term that usually refers to art which combines elements of both romanticism and realism. Although the terms "romanticism" and "realism" have been used in varied ways, they are typically seen as opposed to one another. Romantic realists combine elements from each tradition.

The term has long standing in literary criticism. For example, Joseph Conrad's relationship to romantic Realism is analyzed in Ruth M. Stauffer's 1922 book Joseph Conrad: His Romantic Realism. Liam O'Flaherty's relationship to romantic realism is discussed in P.F. Sheeran's book The Novels of Liam O'Flaherty: A Study in Romantic Realism. Fyodor Dostoyevsky is described as a romantic realist in Donald Fanger's book, Dostoevsky and Romantic Realism: A Study of Dostoevsky in Relation to Balzac, Dickens, and Gogol. Historian Jacques Barzun argued that romanticism was falsely opposed to realism and declared that "...the romantic realist does not blink his weakness, but exerts his power."

The term also has long standing in art criticism. Art scholar John Baur described it as "a form of realism modified to express a romantic attitude or meaning". According to Theodor W. Adorno, the term "romantic realism" was used by Joseph Goebbels to define the official doctrine of the art produced in Nazi Germany, although this usage did not achieve wide currency.

The writer/philosopher Ayn Rand described herself as a romantic realist, and many followers of her Objectivist philosophy who work in the arts apply this term to themselves. Rand defined romantic realism as a portrayal of life "as it could be and should be." "Could be" implied realism, as contrasted with mere fantasy. "Should be" implied a moral vision and a standard of beauty and virtue. This combination is based on the idea that heroic values, and similar themes, are rational and realistic, as a romantic realist wouldn't believe in a necessary dichotomy between 'romanticism' and 'realism.' Ayn Rand's romantic realism differs from Goebbels' in the sense that its chief aim is not to educate in the sense of propaganda, but to project the artist's metaphysical values.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romantic_realism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cynical_Realism

World (Social) Realist Art (Index of Countries)

This blog page is part of an ongoing project by artist and part-time lecturer Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin (http://gaelart.net/) to explore Realist / Social Realist art from around the world. The term Realism is used in its broadest sense to include 19th century Realism and Naturalism as well as 20th century Impressionism (which after all was following in the path of Courbet and Millet). Social Realism covers art that seeks to examine the living and working conditions of ordinary people (examples include German Expressionism, American Ashcan School and the Mexican Muralists).

Click here for (Social) Realist Art Definitions, World (Social) Realism and Global Solidarity, Art and Politics, Social Realism in history and Country Index.

Suggestions for appropriate artists from around the world welcome to caoimhghin@yahoo.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment