A poster of the miniseries Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99.

The documentary Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 was most decidedly a depiction of a catastrophe. Watching the concert progress (or regress) from excitement to disaster was a spine-chilling experience. Over time the problems depicted in the film got unbelievably worse. The concert’s collapse into complete chaos as the hyped-up concert-goers set much of the event equipment on fire looked more like a depiction of hell on the walls of a medieval church.

The concert, designed to emulate the 30th anniversary of the original 1969 concert, was held in the former Griffiss Air Force Base in upstate New York, USA, with many popular acts of the time such as DMX, Limp Bizkit, Korn, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Alanis Morissette, Kid Rock, Metallica, and Creed.

The festival was held from July 22-25, 1999, and the heat was estimated to be 38°C (100°F) with little shade and swathes of concrete and asphalt magnifying the hot conditions. Very little shade and not enough grass meant that some festival-goers were even forced to camp on the asphalt.

Bassist Tim Commerford (left) of Rage Against the Machine

burns the American flag onstage during “Killing in the Name” at Woodstock ’99.

While the first couple of days went fairly well the atmosphere

declined after the Saturday night performance by Limp Bizkit. Fans who

were already frustrated by the price gouging of water and food began to

tear plywood off the walls and the audio tower. Thousands of candles,

distributed during the day for a candlelight vigil, were used to start

bonfires. By the time the last band had finished on stage the festival

site looked post-apocalyptic with troopers and police moving the

concert-goers away from the stage. The whole debacle

had seen overflowing toilets, sexual assaults, ATMs and semi-tractor

trailers looted and destroyed, three deaths and over 5,000 medical cases

reported.

The bands were accused of inciting violence. Limp Bizkit’s vocalist Fred Durst shouted out during their performance: “We already let all the negative energy out. It’s time to reach down and bring that positive energy to this motherfucker. It’s time to let yourself go right now, ’cause there are no motherfuckin’ rules out there.” The crowd were already a hyped-up, heaving mass of jumping, crowd-surfing and moshing humanity moving to the music which soon turned to violence and destruction of the event site itself. In other words, this was mass catharsis on a grand scale, an iconic symbol of the power of one large event to symbolise the contemporary feelings of a frustrated generation freed from the ‘rules’.

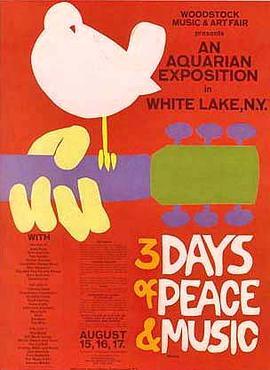

Promotional poster designed by Arnold Skolnick.

Originally, the bird was perched on a flute.

Woodstock ’69

The original 1969 Woodstock similarly freed the audience-goers from

the ‘rules’ of the time as the hippie generation smoked pot, took

psychedelic drugs, and even lived in communes outside of the established

system. What became known as the counterculture

movement of the 1960s was formed in opposition to the US involvement in

the Vietnam War and left “a lasting impact on philosophy, morality,

music, art, alternative health and diet, lifestyle and fashion.”

However, this counterculture also contained more serious elements that threatened the status quo itself. Young people were getting involved in revolutionary anarchist and socialist movements. Many gravitated towards the New Left: “a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights, environmentalism, feminism, gay rights, gender roles and drug policy reforms.” Others became involved in the political forms of Marxism and Marxism–Leninism, such as the New Communist movement which “represented a diverse grouping of Marxist–Leninists and Maoists inspired by Cuban, Chinese, and Vietnamese revolutions. This movement emphasized opposition to racism and sexism, solidarity with oppressed peoples of the third-world, and the establishment of socialism by popular revolution.” According to historian and NCM activist Max Elbaum, the movement had an estimated 10,000 cadre members at its peak influence.

With opposition growing to the Vietnam war in 1968 and student demonstrations taking place in Poland [March 1968 protests] and in France [May 1968 campus uprisings] the New Left ideology began to filter into music and cinema.

In 1967 Jean-Luc Godard directed the film La Chinoise about a group of young Maoist activists in Paris, and in 1968 the Beatles released their song

‘Revolution’ which contained the lyrics, “But if you go carrying

pictures of Chairman Mao / You ain’t gone make it with anyone anyhow”.

The activism of the time was also reflected in the Rolling Stones single of 1968, ‘Street Fighting Man’.

in Washington, D.C. on October 21, 1967.

Turn on, tune in, drop out

By the time the Woodstock festival came around in 1969, the themes of love and peace were combined with Timothy Leary’s “Turn on, tune in, drop out”, an evocation to look into oneself (with the use of psychedelic drugs) rather than to look outwards and change society.

The importance of Woodstock is its iconic value as a symbol of revolt for a generation, as Elvis Presley, for example, was seen in the 1950s. One event, one individual, or one band can become elevated to a symbolic level representing something radical and even revolutionary to the people who were there, (and the people who wish they had been there). This can also be seen in the Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 interviewees who said that despite the chaos, they would go again, and that it had been the event of their lives. The huge numbers of fans involved in each concert, from 200,000 to 400,000 people, give these events cultural legitimacy and something to aspire to despite the fact that on an ideological level they work against the possibility of real change. ‘Dropping out’ in ’69 or catharsis in ’99 may have been satisfying in their times but little has changed politically since then. Is it time now for a mass music festival celebrating identity politics as the new revolution in cultural thinking, and the ultimate in divide and rule politics?

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country here. Caoimhghin has just published his new book – Against Romanticism: From Enlightenment to Enfrightenment and the Culture of Slavery. Against Romanticism looks at philosophy, politics and the history of 10 different art forms arguing that Romanticism is dominating modern culture to the detriment of Enlightenment ideals. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

No comments:

Post a Comment