Zombies and Replicants, The Choreography of Human Dignity: Hollywood’s “Blade Runner 2049” and “World War Z”

The acceptance of

violence in cinema today has become the norm. In almost every genre of

cinema (even in comedies [Kick Ass] and musicals [Sweeney Todd]) today

extreme violence can crop up at some point during the movie. Some film

genres are based on violence: horror, war, westerns, crime, terror.

It is believed that 863 million people live in slums and around 65 million people live in refugee camps.

We live in a global system which has created these problems but is not

able to resolve them. Moreover, these numbers are constantly increasing

and no state or international organisation has been able to reverse the

figures, hence the anxiety.

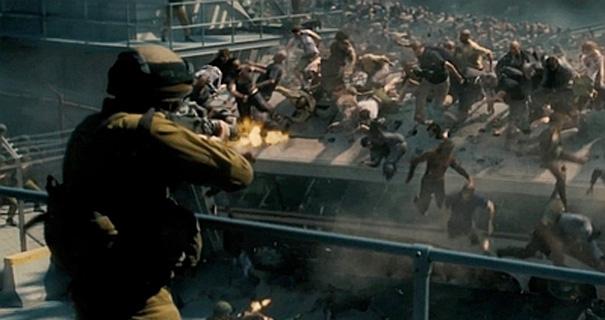

The use of violence to

destroy the replicants and zombies is depicted in very graphic scenes.

We are being familiarised with regular violent scenes of ‘people’ being

killed with machine guns, shot point blank in the head, knifed in the

heart or executed on the spot. We do not question the morality of such

actions because they are ‘androids’, ‘robots’, ‘zombies’, etc. However,

when such behaviour is shown in films where humans are depicted, do we

question it? Do we think about issues of human dignity, justice before

the law, the Geneva Conventions, the abolition of capital punishment?

Are we becoming like the mob who shouts ‘take him out’?

Blocking means working out the the details of each actor’s moves during filming of each scene. Actors must learn the choreography of hand to hand combat (slaps and punches) and how to work with a gun to look authentic and realistic. The huge increase in realistic violent scenes in cinema has had its physical toll on actors accruing injuries in combat scenes, an increase in stunt actors and ever more realistic computer graphics.

World War Z

On a symbolic level the

human body is becoming more objectified as a dehumanised punch bag,

while on a philosophical level there is a move away from humanism to an

apocalyptic ‘posthuman’ view. We are becoming less and less shocked at

the sight of torture, pumping blood, bones sticking out, severed limbs,

massive gashes in the body, knife wounds and multiple bleeding bullet

holes.

It wasn’t always like this. In the 1930s Hollywood adopted the self-imposed Hays Code (officially

the Motion Picture Production Code) which set out guidelines on what

could be depicted in films. While the code covered many aspects of

society especially in relation to crime, nudity and religion, it also

recommended that ‘special care be exercised in the manner in which the

following subjects are treated’ such as: ‘Arson’, ‘The use of firearms’,

‘Brutality and possible gruesomeness’, ‘Technique of committing murder

by whatever method’, ‘Actual hangings or electrocutions as legal

punishment for crime’ and ‘Rape or attempted rape’.While some may laugh at the prudery and censorship of cinema during those times (which had been rejected by the early 1960s), others see a more human era when violence was implied rather than graphically depicted.

Kick Ass

The issues at stake here

though are not the problems of censorship or prudery but the depiction

and role of violence in cinema. Cui bono? In society who benefits from

the constant portrayal of interhuman and internecine violence in the

movies? Cinema has a mass popular base and therefore will influence

attitudes in society as people watch and discuss films they see in

theatres and on television. Cinema is also extremely costly to make and

therefore its content is highly constrained by the type of subject

matter elites wish to be viewed. It is often said that the director gets

first cut and the producers determine the rest.

Fortunately, cinema also has a tradition of film making which revolves around working class unity and solidarity. This comes down to individual writers and directors with a social consciousness who over the years have made films that explored the lives and struggles of ordinary people. Filmmakers themselves are aware of the potential for decline of a film industry without a code of ethics, where anything goes. In recent years the president of the Union of Cinematographers of Russia, film director Nikita Mikhalkov, initiated the creation of an ethics charter for the film industry there. The code would be a voluntary, self-regulation of the industry. It is interesting to note that in the United States the Golden Age of Hollywood coincided with the time of the Hays Code.

In the discussion about violence in the cinema part of the debate revolves around just and unjust violence. However, one may ask if the depiction of extreme violence in the revenge of the oppressed is reason enough for the acceptability of its portrayal? Even here the dignity of the human being implies that the ethical imperative is to move away from the horror of extreme violence for the possibility of the creation of a genuinely civilised future.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists

of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish

history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on

cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist

and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by

country at http://gaelart.blogspot.ie/ .

No comments:

Post a Comment