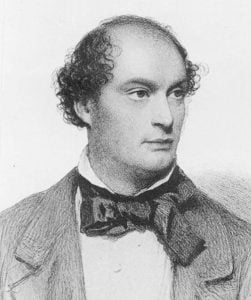

Snap-Apple Night, painted by Daniel Maclise in 1833, shows

people feasting and playing divination games on Halloween in Ireland.

It was inspired by a Halloween party he attended in Blarney, Ireland, in

1832.

“We make up horrors to help us cope with the real ones.” – Stephen King

Halloween is creeping up on us again replete with all its ghostly traditions celebrated all over the world.

Also

known as All Saints’ Eve, it is the time in the liturgical year or

Christian year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints

(hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed. It is followed by All

Saints’ Day, also known as All Hallows’ Day on the 1 November, and All

Souls’ Day, a day of prayer and remembrance for the faithful departed,

observed by certain Christian denominations on 2 November.

However,

it is also believed that Halloween is rooted in the ancient pagan

Gaelic festival of Samhain which marks the change of seasons and the

approach of winter. Samhain begins at sunset on October 31 and continues

until sunset on November 1, marking the end of harvest and the start of

winter. This Celtic pagan holiday followed the great cycle of life as

part of their year-round celebrations of nature along with Imbolc (February 1), Beltane (May 1) and Lughnasadh (August 1).

During Samhain people would:

“bring

their cattle back from the summer pastures and slaughter livestock in

preparation for the upcoming winter. They would also light ritual

bonfires for protection and cleansing as they wished to mimic the sun

and hold back the darkness. It was also a time when people believed that

spirits or fairies (the Aos Sí ) were more likely to pass into our

world. […] Dead and departed relatives played a central role in the

tradition, as the connection between the living and dead was believed to

be stronger at Samhain, and there was a chance to communicate. Souls of

the deceased were thought to return to their homes. Feasts were held

and places were set at tables as a way to welcome them home. Food and

drink was offered to the unpredictable spirits and fairies to ensure

continued health and good fortune.”

Dancing around the bonfire. The Graphic | 7 January 1893

The Celts believed in an afterlife called the Otherworld which was similar to this life but “without all the negative elements like disease, pain, and sorrow.”

Therefore, the Celts had little to fear from death when their soul left their body, or as the Celts believed, their head.

As

Christianity spread in pagan communities, the church leaders attempted

to incorporate Samhain into the Christian calendar. The Roman Empire had

conquered the majority of Celtic lands by A.D. 43 and combined two

Roman festivals, Feralia and Pomona with the traditional Celtic

celebration of Samhain. Feralia was similar to Samhain as the Romans commemorated

the passing of their dead, while Pomona, whose symbol was the apple,

was the Roman goddess of fruit and trees, and may be the origin of the

apple games of Halloween.

Some centuries later the church moved again to supplant the pagan traditions with Christian ones:

“On

May 13, A.D. 609, Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Pantheon in Rome in

honor of all Christian martyrs, and the Catholic feast of All Martyrs

Day was established in the Western church. Pope Gregory III later

expanded the festival to include all saints as well as all martyrs, and

moved the observance from May 13 to November 1. By the 9th century, the

influence of Christianity had spread into Celtic lands, where it

gradually blended with and supplanted older Celtic rites. In A.D. 1000,

the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to honor the dead.”

While

on the surface the changes from the Celtic Otherworld to the Christian

concepts of Heaven, Purgatory and Hell may not seem very radical yet

when one looks further into the different beliefs about the afterlife a

very different story emerges.

The Otherworld

The Celtic Otherworld

is “more usually described as a paradisal fairyland than a scary place”

and sometimes described as an island to the west in the Ocean and “even

shown on some maps of Ireland during the medieval era.” It has been

called, or places in the Otherworld have been called,

“Tír nAill (“the other land”), Tír Tairngire (“land of promise/promised

land”), Tír na nÓg (“land of the young/land of youth”), Tír fo Thuinn

(“land under the wave”), Tír na mBeo (“land of the living”), Mag Mell

(“plain of delight”), Mag Findargat (“the white-silver plain”), Mag

Argatnél (“the silver-cloud plain”), Mag Ildathach (“the multicoloured

plain”), Mag Cíuin (“the gentle plain”), and Emain Ablach (possibly

“isle of apples”).”

As can be seen from the names given to the places of the Otherworld there are two important, salient points.

One is the positive, almost welcoming aspect of the descriptions

implied, and secondly their close relationship with nature and places in

the real world. The Otherworld is described “either as a parallel world

that exists alongside our own, or as a heavenly land beyond the sea or

under the earth,” and could be entered through “ancient burial mounds or

caves, or by going under water or across the western sea.”

We may then ask who could enter the Otherworld in the afterlife?

“Although

there are no surviving texts from the continent which comment on this,

on the basis of comparisons with comparable societies and burial

practices we can guess that both the gods and the ancestral dead were

believed to inhabit the Otherworld. The earliest literary texts in Irish

reflect exactly this idea.”

These

deductions about the afterlife then reflect the nature-based ideology

of pagan religion which is focused on the cycles of nature, and also the

fact that we ourselves are part of that nature, thus both the ancestral

dead and the gods inhabited the Otherworld. It seems that the dead

entered the Otherworld fairly quickly and could even return to visit the

living when the darkness started to take over from the light at

Samhain. Even the living could visit the Otherworld but these visits

would have their own drawbacks, for example, Oisín discovers that what had only seemed a short stay in Tír na nÓg had been hundreds of years in the real world.

Ghosts walk the night in Brittany by F. De Haenen | The Graphic | 5 November 1910

Christian Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory

The

differences between nature-based paganism and the Master and Martyr

ethics of Christianity mean that entry to heaven is not guaranteed and

may even be delayed for a long time in purgatory. For example:

“Christianity

considers the Second Coming of Jesus Christ to entail the final

judgment by God of all people who have ever lived, resulting in the

approval of some and the penalizing of most. […] Belief in the Last

Judgment (often linked with the general judgment) is held firmly in

Catholicism. Immediately upon death each person undergoes the particular

judgment, and depending upon one’s behavior on earth, goes to heaven,

purgatory, or hell. Those in purgatory will always reach heaven, but

those in hell will be there eternally.”

Hell

is often depicted with fire and torture of the guilty. Thus,

Christianity brings a strong element of fear into perceptions of the

afterlife. The people whose behaviour needs to be controlled are

frightened into being good and given long promises about eventual

eternal bliss at the end of time.

The

patriarchal element of Christianity and its desire to control and

direct the remnants of pagan religion gave rise to other important

aspects of Halloween. The dark symbolism of witches on broomsticks with

black cats are an essential element of the Halloween imagery. By late

medieval/early modern Europe, fears about witchcraft rose to fever pitch

and sometimes led to large-scale witch-hunts. The Church saw these

women (whose knowledge of nature was transformed into healing

homoeopathic treatments) as a threat to their authority and demonised

them before their own communities.

The witches

“occasionally functioned as midwives, assisting the delivery and birth

of babies, aiding the mother with different plant-based medicines to

help with the pain of childbirth. […] The word Witch comes from the word

for ‘wise one’ that was ‘Wicca’, and who were once considered wise soon

became something to be feared and avoided.”

“Halloween Days”, article from American newspaper, The Sunday Oregonian, 1916

Like

many traditional festivals Halloween has different historical sources,

pagan and Christian, that have come together to form the holiday as we

know it today.

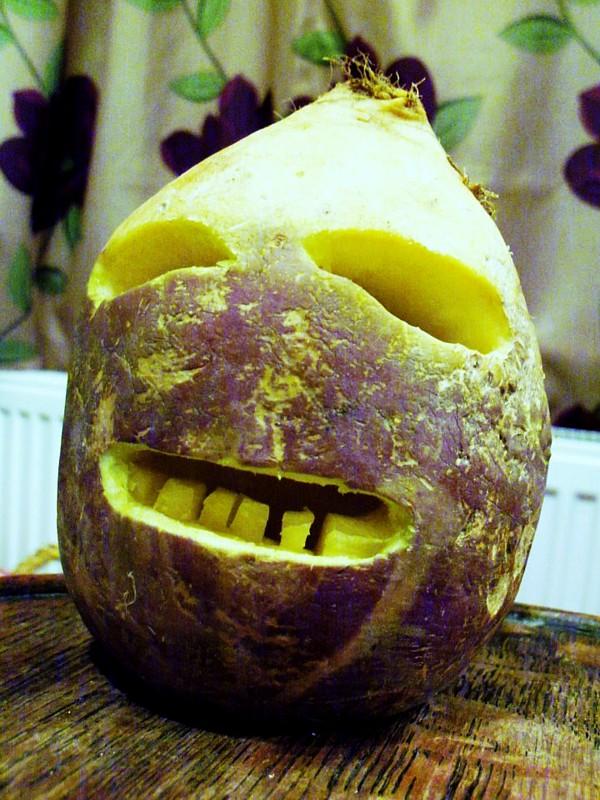

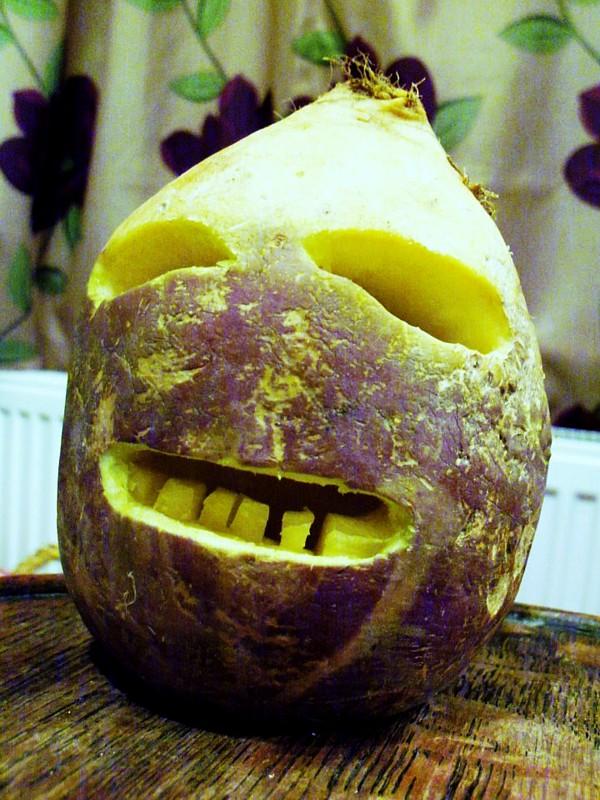

Jack-o’-lantern

Jack-o’-lantern

represents the soul caught between heaven and hell who can know no rest

and must wander on the earth forever. It is believed to originate in an

old Irish folk tale from the mid-18th century which tells of Stingy

Jack, “a lazy yet shrewd blacksmith who uses a cross to trap Satan.”

A plaster cast of a traditional Irish Jack-o’-Lantern in the Museum of Country Life, Ireland. Rutabaga or turnip were often used.

Jack

tricks Satan who lets him go only after he agrees to never take his

soul. When the blacksmith dies he is considered too sinful to enter

heaven. He could not enter hell either and asks Satan how he will be

able to see his way in the dark. Satan’s response

was to toss him “a burning coal, to light his way. Jack carved out one

of his turnips (which were his favorite food), put the coal inside it,

and began endlessly wandering the Earth for a resting place.”

The

Irish emigrants to the United States are believed to have switched the

turnip for a pumpkin as it was more accessible and easier to carve.

Ironically, in Ireland now, pumpkins are grown and sold to make modern

Jack-o’-lanterns.

Modern carving of a Cornish Jack-o’-Lantern made from a turnip.

Door to Door Traditions

Another

American tradition, trick-or-treating, has also taken root in Ireland

in recent decades. As a child growing up in the United States, I also

went trick-or-treating in Boston. However, after our move to Dublin, our

trick-or-treating questions at Halloween were met with bewilderment as

Irish people were used to a simple request for ‘anything for the

Halloween party’.

The

tradition of going door to door on Halloween may come from the belief

that supernatural beings, or the souls of the dead, roamed the earth at

this time and needed to be appeased. In Europe, from the 12th century,

special ‘soul cakes’ would be baked and shared. People would pray for

the poor souls of the dead (in purgatory) in return for soul cakes. In

Ireland and Scotland “mumming and guising (going door-to-door in

disguise and performing in exchange for food) was taken up as another

variation on these ancient customs. Pranks were thought to be a way of

confounding evil spirits. Pranks at Samhain date as far back as 1736 in

Scotland and Ireland, and this led to Samhain being dubbed ‘Mischief

Night.’”

Antrobus Soul Cakers at the end of a performance

in a village hall in or near Antrobus, Cheshire, England in the mid

1970s. The Soul Cakers are a traditional group of mummers, who perform

around All Soul’s Day (October 31st, Hallowe’en) each year. The

characters are (left to right) Beelzebub, Doctor, Black Prince,

Letter-In, Dairy Doubt, King George, Driver, Old Lady, and Dick, the

Wild Horse in the foreground.

Antrobus Soul Cakers at the end of a performance

in a village hall in or near Antrobus, Cheshire, England in the mid

1970s. The Soul Cakers are a traditional group of mummers, who perform

around All Soul’s Day (October 31st, Hallowe’en) each year. The

characters are (left to right) Beelzebub, Doctor, Black Prince,

Letter-In, Dairy Doubt, King George, Driver, Old Lady, and Dick, the

Wild Horse in the foreground.

It has also been suggested

that trick-or-treating “evolved from a tradition whereby people

impersonated the spirits, or the souls of the dead, and received

offerings on their behalf.” It was thought that they “personify the old

spirits of the winter, who demanded reward in exchange for good

fortune”. Impersonating these spirits or souls was believed to protect

oneself from them.

Thus,

while Halloween may have become highly commercialised in recent years

it is still an important custom that brings people and families together

in their communities. It still marks an important part of the annual

cycles of nature as the bountifulness of harvestime is contrasted with

the bareness of winter. It prepares us psychologically for the dark days

ahead. In the past Halloween allowed people to celebrate the completion

of the work of life (the production of food) to having the time to

contemplate the absence of their forebears: the people who gave them

life, nurtured them, and taught them the skills of survival. It is a

time to make the young generation aware of their parents’ temporary

existence too, in a fun way.

Halloween

is a time for confronting our basic fears about death and darkness. It

is a time to remember the ancestral spirits of past generations who have

‘passed’ (a word that has become more popular than ‘died’ in recent

years) through the thin veil between life and death. And, most

importantly, a time to rethink our relationship with nature.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists

of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish

history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on

cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist

and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by

country here.

Caoimhghin has just published his new book – Against Romanticism: From

Enlightenment to Enfrightenment and the Culture of Slavery, which looks

at philosophy, politics and the history of 10 different art forms

arguing that Romanticism is dominating modern culture to the detriment

of Enlightenment ideals. It is available on Amazon (amazon.co.uk) and the info page is here.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).