“And such should childhood ever be,

The fairy well; to bring

To life’s worn, weary memory

The freshness of its spring.

But here the order is reversed,

And infancy, like age,

Knows of existence but its worst,

One dull and darkened page;—”

by Letitia Elizabeth Landon – The Vow of the Peacock and Other Poems (1835)

(A Christmas Carol and It's a Wonderful Life)

Two girls protesting child labour (by calling it child slavery) in the 1909 New York City Labor Day parade.

Introduction

The idea of a child-centred Christmas is taken for granted now but in Dickens’ time it was not so assured. A high child mortality rate, child labour, poverty and, a colder, more utilitarian attitude towards children prevailed. Dickens’ own childhood experiences were bad as he was set to work long hours in Warren’s Blacking Factory while his father and family languished in a debtors prison. Dickens wanted to write a pamphlet about children but decided a dramatic story would be more effective. His book, A Christmas Carol, while sales were slow initially, went on to become hugely successful and influential, and has never been out of print since.

Dickens at the blacking warehouse, as envisioned by Fred Barnard

The theme of redemption is important to both narratives and both stories turn on the idea of a change of heart for the better by the adults. This change affected the lives of the children in each story yet the children were not aware of the dangers they were in. Thus the concept of childhood as ‘the fairy well’ was well developed, and the ‘freshness of its spring’ being considered a jewel that only grows more beautiful with age.

In this essay I will look at some similarities between the two stories and at what has made for their enduring appeal.

A Christmas Carol

While many differing ideas seem have fortuitously come together for Dickens during the writing of A Christmas Carol the focus on children seems to have been the most important. Literary influences are given as The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon by Washington Irving and a Douglas Jerrold essay from an 1841 issue of Punch, ‘How Mr. Chokepear Keeps a Merry Christmas’.

In The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon Irving writes:

“It was the policy of the good old gentleman to make his children feel that home was the happiest place in the world; and I value this delicious home-feeling as one of the choicest gifts a parent could bestow.”

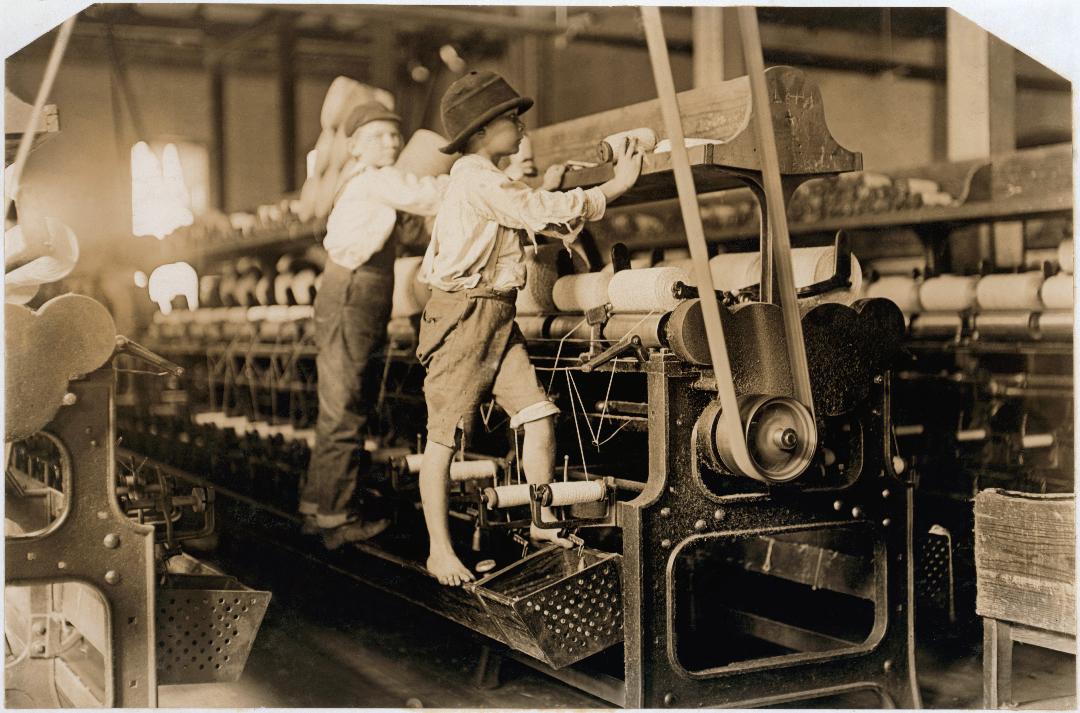

Child labourers, Macon, Georgia, 1909

Dickens was very aware of the tragedy of child workers and legislation being introduce to improve their conditions at the time. The idea of social unity that Dickens utilises at the end of A Christmas Carol is expressed in another passage by Irving in The Sketch-Book, as we hear echoes of the medieval hall resounding to the sounds of the fun organised in the ancient midwinter tradition of the Lord of Misrule, with children once again to the fore:

“After the dinner-table was removed the hall was given up to the younger members of the family, who, prompted to all kind of noisy mirth by the Oxonian and Master Simon, made its old walls ring with their merriment as they played at romping games. I delight in witnessing the gambols of children, and particularly at this happy holiday season, and could not help stealing out of the drawing-room on hearing one of their peals of laughter. I found them at the game of blindman’s-buff. Master Simon, who was the leader of their revels, and seemed on all occasions to fulfill the office of that ancient potentate, the Lord of Misrule, was blinded in the midst of the hall. The little beings were as busy about him as the mock fairies about Falstaff, pinching him, plucking at the skirts of his coat, and tickling him with straws.”Once again the innocent fun of the children is emphasised. However, in Jerrold’s essay ‘How Mr. Chokepear Keeps a Merry Christmas’, a different kind of father is described, one for whom image is more important than feeling. Mr Chokepear is described as “he himself declares, he is ‘the best of fathers’ — the most indulgent of men”, yet he receives the wishes of a happy Christmas “from lips of ice.” He is the best citizen and best Christian but for one thing:

“We have said all CHOKEPEAR’S daughters dined with him. We forgot: one was absent. Some seven years ago she married a poorer husband, and poverty was his only, but certainly his sufficient fault; and her father vowed that she should never again cross his threshold. The Christian keeps his word. He has been to church to celebrate the event which preached to all men mutual love and mutual forgiveness, and he comes home, and with rancour in his heart—keeps a merry Christmas! […] Gentle reader, we wish you a merry Christmas; but to be truly, wisely merry, it must not be the Christmas of the CHOKEPEARS. That is the Christmas of the belly: keep you the Christmas of the heart. Give—give.”Dickens is concerned with genuine Christian ideas of Christmas in A Christmas Carol and not hypocritical ones for show only. Therefore, Scrooge is given the opportunity to redeem himself in a genuine way and this genuine transformation means he will be welcomed into the Cratchit’s house and the house of of his nephew for Christmas celebrations.

Thus Dickens was interested in the idea that the bosses should have a genuine change of heart and not a false annual display of good cheer for their friends. Dickens himself was interested in giving practical help to poor children as well.

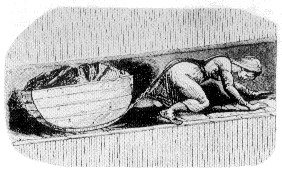

Coal tub – “A succession of laws on child labour,

the so-called Factory Acts, were passed in the UK in the 19th century.

Children younger than nine were not allowed to work, those aged 9–16

could work 16 hours per day per the Cotton Mills Act. In 1856, the law

permitted child labour past age 9, for 60 hours per week, night or day.

In 1901, the permissible child labour age was raised to 12.”

In 1843 Charles Dickens became involved with with the London Ragged Schools Union and donated funds for their upkeep. They were established to provide free education, food, clothing, lodging and other home missionary services for poor children.

As Claire Tomalin writes:

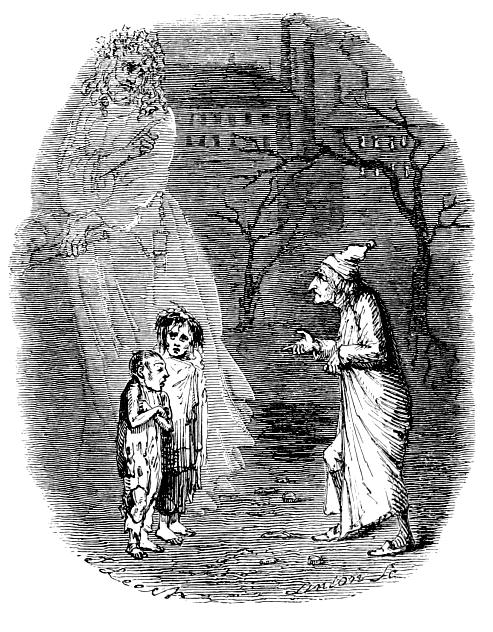

“From his own deep self he drew the understanding that a grown man may pity the child he had been, and learn from that pity, as Scrooge does. It was also his response to the Ragged School he had visited, and the Report of the Children’s Employment Commission he had read a little earlier, which showed that children under seven were put to work, unprotected by any legal constraints, sometimes for ten to twelve hours a day, inspiring the scene in which the Spirit of Christmas Present shows Scrooge two stunted and wolfish children, calling them Ignorance and Want.” [1]Of course, while the children may be the focus of Dickens’ Christmas main story, they must not be aware that they are, thus retaining the sacred concept of childhood. Therefore in the narrative the children are affected only indirectly through the changed habits of the adults. This was Dickens’ strategy – to show that the cruelty of the world and the preciousness of childhood could exist side by side. Thus the adults could change their realm, positively affecting the children’s realm, without the two realms interacting with each other, as happened in Dickens’ own childhood. Dickens’ story also added to the growing belief in the importance of childhood not only for children but also for stable adults as Scrooge was shown to have had a lonely childhood himself.

Ignorance and Want from the original edition of A Christmas Carol, 1843

Many film versions have been made of A Christmas Carol from Scrooge, or, Marley’s Ghost (1901) to A Christmas Carol (2018), a contemporary retelling of the story set in Scotland.

It’s a Wonderful Life

Another popular film with Christmas visions is Frank Capra’s 1946 film, It’s a Wonderful Life. Almost one hundred years after Dickens’ novel was published, Capra’s film shows a very different kind of vision of society. Rather than the atomised society of the poor in Dickens’ London, Capra shows a community being pulled and pushed in different directions by individuals with very different objectives. George Bailey faces off Henry F. Potter who is trying to take over the town with cheap, exploitative housing schemes and by buying up everything of value in the town.

As Bailey faces bankruptcy of the Bailey Brothers’ Building and Loan through the forgetfulness of his uncle (mislaying a lot of money), Potter seizes the opportunity to destroy Bailey’s bank and take over the town completely. When Bailey arrives home distraught he has angry words with all of his children. They become very upset and burst into tears as they have no idea what has come over their normally loving father.

As a result of this disaster, Bailey wishes he had never been born and is shown a vision of what the town would have become had Bailey’s community spirit and camaraderie with his clients not existed: a mean place, decadent and aggressive with no community feeling or community spirit (like Scrooge, mean, aggressive with no community feeling or community spirit). After the negative scenario he experiences, Bailey rushes home to his wife and apologises to each of his children in turn for his earlier outburst thus keeping the adult and child domains separated, while the adults sort out adult problems.

Unlike Scrooge, in It’s a Wonderful Life the individualist money-pincher Potter is not considered important enough to go through the process of redemption (while he is portrayed as a Scrooge type figure), because the poor are now portrayed as existing in a community which can ultimately defend itself from Potter’s attacks: by coming together and using collective action to help Bailey. They look to each other for help and not to the rich bankers.

Although both Scrooge and Bailey lend money, Scrooge gives out money to benefit himself while Bailey gives out money to benefit the community. In the earlier ideology of A Christmas Carol, the wealthy must look after or take pity on the helpless poor. However, while Scrooge must save himself, the community saves Bailey.

George Bailey (James Stewart), Mary Bailey (Donna Reed), and their youngest daughter Zuzu (Karolyn Grimes) in It’s a Wonderful Life.

In A Christmas Carol the poor are everywhere but have no real consciousness of their poverty and struggle against poverty despite the odds. In It’s a Wonderful Life the poor are depicted as belonging to a community but gradually grow more conscious of their weak position and unite to defend themselves.

They develop a growing consciousness of the power of the community to use collective action to fight back against those who would keep them poor. As a result, rather than being solely concerned with their own money and future as was shown earlier in the film, they see the importance of community for their own self-protection just in time, and turn up at Bailey’s house to lend, give, donate any money they have to save the bank and their own future. Thus in It’s a Wonderful Life, its the community that redeems itself.

Both Dickens’ book and Capra’s film carried radical messages for their time. Only two years after A Christmas Carol, German philosopher Friedrich Engels published The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1845, a book written during Engels’ 1842–44 stay in Manchester, important as the city at the heart of the Industrial Revolution. Engels believed that Carlyle was the only British writer who had taken account of the poor and so was not yet familiar with A Christmas Carol. Meanwhile Marx saw Dickens as one of a few ‘splendid’ fiction writers in England, “whose graphic and eloquent pages have issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together.”

While It’s a Wonderful Life depicts the benefits of a community uniting, it was declared suspect by an unnamed FBI agent who watched the film as part of a larger FBI program aimed at detecting and neutralizing Communist influences in Hollywood. The agent believed that ‘communists’ used two common tricks to ‘inject propaganda into the film’, as Kat Eschner writes:

“These two common “devices” or tricks, as applied by the Los Angeles branch of the Bureau, were smearing ‘values or institutions judged to be particularly American’ – in this case, the capitalist banker, Mr. Potter, is portrayed as a Scroogey misanthrope – and glorifying ‘values or institutions judged to be particularly anti-American or pro-Communist’ – in this case, depression and existential crisis, an issue that the FBI report characterized as a ‘subtle attempt to magnify the problems of the so-called ‘common man’ in society.'”The organization handed over these incredibly vague results of its investigation to HUAC (House of UnAmerican Activities) which could have led to McCarthyist Hollywood witch hunts. However, the HUAC decided not to follow up on the smears.

Conclusion

In both A Christmas Carol and It’s a Wonderful life, a common theme is the idea that people can change for the better and have a happier life by questioning their own selfish values and motives and by realising that there are greater forces at work which must be reckoned with for survival. Scrooge’s isolation from friends, family and employees led him to fear a lonely death and Marley’s fate. Bailey’s customers also realise that looking after number one might allow them to get by on the level of their own petty concerns, but when something seriously threatening to their homes and families appears on the horizon they are able to club together to prevent the worst. Ultimately it is the children who benefit as the adults unite and solve problems rather than sharing the burden with their children, and in the long term that also makes for a more stable community.

The idea of sheltering children from the cruel world, rather than throwing them head first into it, is still an important issue in the world’s poorest countries today where around one in four children are believed to be engaged in child labour.

On an individual level and on a community level these two stories

have everlasting appeal because they are still relevant today. The

continuing political, financial, and climate crises of the 21st century

mean that the need for individual self-questioning and/or community

action will never cease to be important, and maybe even be life-saving

as the new century wears on.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork

consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well

as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing

based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of

Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed

country by country here. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization.

Note

[1] Claire Tomalin, Charles Dickens: A Life (Viking: London, 2011) p149