“Swift has sailed into his rest;

Savage indignation there

Cannot lacerate his breast.

Imitate him if you dare,

World-besotted traveller; he

Served human liberty.”

Savage indignation there

Cannot lacerate his breast.

Imitate him if you dare,

World-besotted traveller; he

Served human liberty.”

W. B. Yeats translation of Jonathan Swift’s Latin epitaph

Introduction

In this continuing series on the effects of Romantic and Enlightenment ideas on modern culture, I have looked at the negative aspects of Romanticism on fine art, music, cinema and politics. In this article I will examine Romantic and Enlightenment ideas on literature from the eighteenth to the 21st century showing how from the earliest days literature has been a battleground for the future of culture itself. Enlightenment influences on literature led to the concept of progressive culture which took many forms through to today. From realism, social realism, the proletarian novel, socialist realism, concepts of progressive culture have constantly changed in opposition to Romantic ideas of ‘art for art’s sake’. Here we will look at these changes over time and and finish by examining suggested definitions of progressive literature for the future.

Romantic and Enlightenment literature

The Enlightenment was an intellectual movement during the eighteenth century in which philosophers and scientists spread their ideas through literary salons, coffeehouses and printed books, pamphlets and journals. It was a time of dramatically increasing literacy and a growing reading audience encouraged by cheaper printed material.

Reading habits changed from public reading of a few books, to extensive private reading as books got cheaper. The Enlightenment was a time for satirists and humorists attacking the conservative monarchical institutions of the eighteenth century. Writers such as Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope in Ireland and England and Voltaire in France blended criticism, satire and fiction into a new type of literature. While Enlightenment influences tended to be based on reason and science looking outwards, the Romantic reaction stressed “sensibility”, or feeling and tended towards human psychology and looking inwards.

The title page to Swift’s 1735 Works, depicting the author in the Dean’s chair, receiving the thanks of Ireland. The Horatian motto reads, Exegi Monumentum Ære perennius, “I have completed a monument more lasting than brass.” The ‘brass’ is a pun, for Wood’s halfpennies (alloyed with brass) lie scattered at his feet. Cherubim award Swift a poet’s laurel.

Romantic literature put more emphasis on themes of isolation, loneliness, tragic events and the power of nature. A heroic view of history and myth became the basis of much Romantic literature. The Scottish poet James Macpherson’s Ossian cycle of poems (published in 1762) were a huge influence on Goethe and Walter Scott. Ivanhoe, published in 1819, was Walter Scott’s most popular historic novel and reflected the Romantic interest in medievalism. In Germany, it was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) that had the most influence on burgeoning German Romanticism. However, the introverted, fatalistic aspect of Young Werther was eventually rejected by Goethe himself who described the Romantic movement as “everything that is sick.”

Literary Realism

Enlightenment ideas took off in a different direction as the scientific method had its influence on literature in the form of the depiction of “objective reality”. Known as Literary Realism and beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, writers such as Stendhal in France and Alexander Pushkin in Russia led the realist movement with a view to representing “subject matter truthfully, without artificiality and avoiding artistic conventions, as well as implausible, exotic and supernatural elements.”

In this sense Realism opposed Romantic idealisation or dramatisation and focused on lower class society’s everyday activities and experiences in a more empirical way. This led to the the development of the social novel which can be seen as a “work of fiction in which a prevailing social problem, such as gender, race, or class prejudice, is dramatized through its effect on the characters of a novel” and covering topics such as “poverty, conditions in factories and mines, the plight of child labor, violence against women, rising criminality, and epidemics because of over-crowding, and poor sanitation in cities.”

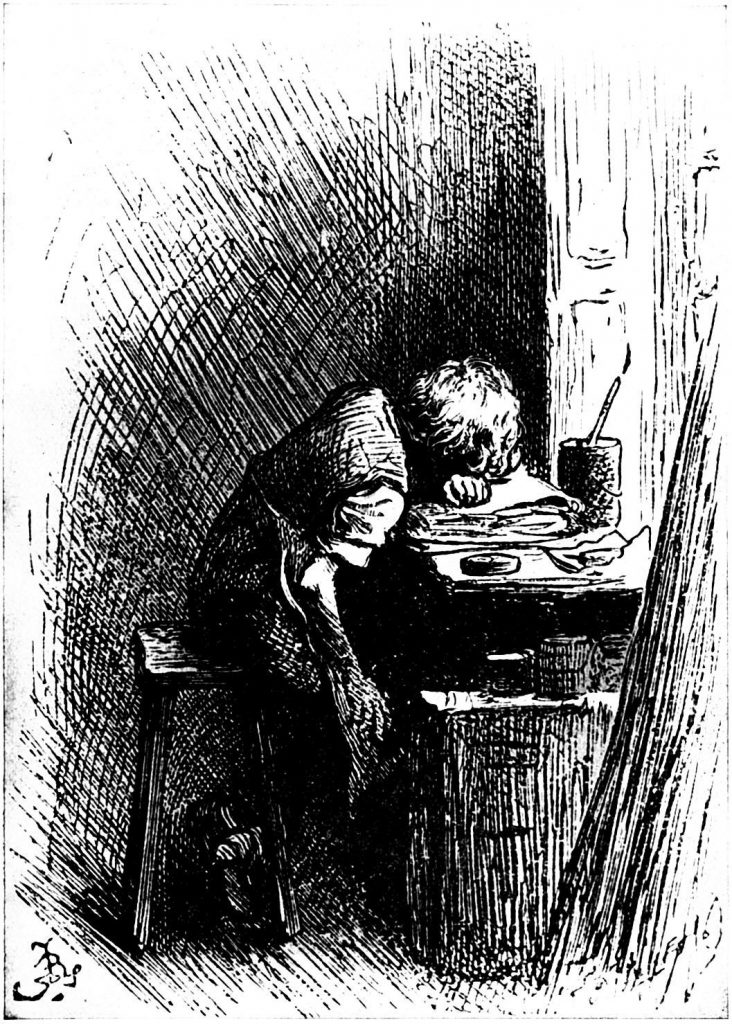

Early examples of the social novel were Charles Kingsley’s Alton Locke (1849) and Elizabeth Gaskell’s first industrial novel Mary Barton (1848). However, it was Charles Dickens whose depictions of poverty and crime that shocked readers the most and even led Karl Marx to write that Dickens had “issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together”. Dickens novels Oliver Twist (1839) and Hard Times (1854) explored many important social questions relating to the negative aspects of the industrial revolution.

Illustration by Fred Bernard of Dickens at work in a shoe-blacking factory after his father had been sent to the Marshalsea, published in the 1892 edition of Forster’s Life of Dickens.

Around the same time in France, Victor Hugo published his historical novel Les Misérables (1862). The novel follows the lives of several characters and in particular the struggles of the an ex-convict Jean Valjean. Hugo uses the from to elaborate his ideas on many topics from the history of France to politics, justice, religion and even the architecture and urban design of Paris. He outlines his purpose in a famous Preface to Les Misérables in which he writes:

“So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilization, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age—the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of women by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night—are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a yet more extended point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.”

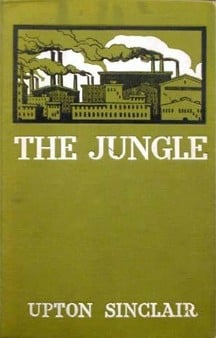

The Jungle is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair (1878–1968).

The American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair (1878–1968) put such ideas into practice when he spent seven weeks gathering information while working incognito in the meatpacking plants of the Chicago stockyards in 1904. This resulted in the 1906 novel, The Jungle, which exposed the harsh conditions, health violations, and unsanitary practices in the American meat packing industry of the time. The novel was hugely controversial at the time with publishers initially refusing to publish it but eventually the conditions described in the book led to public pressure to pass the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act.

The proletarian novel

As the nineteenth century progressed enlightenment ideas were taken up by socialist movements and produced a new class-conscious proletarian literature created by working class writers. The proletarian novel is a political form of the social novel which comments on political events and was used to promote social reform or political revolution among the working classes.

The proletarian novel achieved significance in different countries in the early twentieth century. It came to prominence during a time of rising fascism during the 1930s when Nazi book burnings were being carried out in Germany and Austria. The political polarisation is evidenced by the writers meetings that took place at the time when the First American Writers Congress (1935) in the USA, the International Writers’ Congress for the Defence of Culture (1935) in France, and the First Congress of Soviet Writers (1934) in the Soviet Union were all held.

Progressive literature emphasised social development and was part of the general progressive movement of those who wanted science and technology to lead the way for a better society for all. It was opposed to the content and values of regressive literature such as:

“Despair, mysticism, the thought that man is helpless and incapable of building one’s own future complete degradation, sexual vagaries, respect for war and massacres, condescension to cultural values, faith in the evil of man and the disbelief in the generosity of mankind, hatred towards ideals, all of these are the main trends of regressive literature. Such regressive trends are advertised behind a veil of arguments which state that art does not have any other responsibility beyond that of being art in itself.”Such a description of regressive literature covers many aspects of Romantic ideas in culture too.

What is progressive culture today?

Ngugi wa Thiong’o. His work includes novels, plays, short stories, and essays, ranging from literary and social criticism to children’s literature.

The multilingual Indian writer K. Damodaran (1912 – 1976) set out his beliefs on progressive literature as a literature in which the writer should adopt a scientific approach towards viewing things, try to eradicate superstitions and blind practices, and not isolate himself or herself from society. He also believed in literatures that preserved regional languages.

One writer who puts such ideas into action in both fiction and prose

is the Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o (not to mention Swiftian satire).

While there are many African writers writing social literature about

the lives of African people today, Ngugi has been important for his

emphasis on the formal qualities of language as well the radical content

of his novels. His use of his local Gikuyu language as the original

language of his novels is an important anti-colonial aspect of his

purpose for writing. As English moves from being the dominant hegemonic

language of earlier colonised countries such as Ireland and Kenya to

being super hegemonic globally due to the influence of satellite

broadcasting and the internet, such linguistic strategies of Ngugi may

become more significant when formally ‘major’ languages themselves also

start to come under threat.

Conclusion

While there have been obvious influences of Romanticism on writers like Dickens, it could be argued that the realist impulse was a stronger drive and that Dickens knew and understood the poverty he described so well in his novels. This drive to incorporate and expose all forms of oppression in literary work could be described as one of the fundamentals that links the writers in the centuries old development of progressive literature. But, however progressive literature is defined into the future, it can be sure that its writers will not be appreciated for exposing the dark side of human oppression except by those whose voices too often remain unheard.

Conclusion

While there have been obvious influences of Romanticism on writers like Dickens, it could be argued that the realist impulse was a stronger drive and that Dickens knew and understood the poverty he described so well in his novels. This drive to incorporate and expose all forms of oppression in literary work could be described as one of the fundamentals that links the writers in the centuries old development of progressive literature. But, however progressive literature is defined into the future, it can be sure that its writers will not be appreciated for exposing the dark side of human oppression except by those whose voices too often remain unheard.

All images in this article are from Wikimedia

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork

consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well

as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. He is an Irish speaker and holds a PhD in Language and Politics

(Dublin City University) which is

published under the title Language from Below: The

Irish Language, Ideology and Power in 20th-Century Ireland.

His blog of critical writing

based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of

Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed

country by country here.

He is a Research Associate and Culture

and the Arts Correspondent of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG),

Montreal, Canada.