Introduction

Ever since the achievements of Renaissance humanism with the

triumph of art over nature, with the development of new artistic

techniques (the optics of perspective, the structure of anatomy, the

mixing of pigments, and the development of movement) art was

strengthened and, combined with the scientific explorations and

achievements of the Enlightenment, led to the idea that Man could become

stronger and better and hold an optimistic view of the future. He could

improve his well-being and even take control of nature to create a

better life for all. This view continued through the decades and was

associated with social revolutions and political activity which

connected progressive ideas about society to artistic forms of

expression which would illustrate and advance the hopes and desires of

the masses for a better life and future. These artistic movements

changed and developed from the Enlightenment to Realism to Social

Realism and then to Socialist Realism as artists both inspired and

reflected the people’s progressive movements the world over.

However, at every juncture, oppositional movements also stepped in

and opposed progressive change and revolution by the people; from the

Romantic movement in Revolutionary France to the Modernist movement to

Postmodernism and now Metamodernism. These movements have derided every

aspect of the progressive forces, from the quietist “l’art pour l’art”

of Romanticism to the attack on artistic form by Modernism, to the later

attack on ideological content by Postmodernism and now the

‘oscillation’ between the two (form and content) of Metamodernism, a

movement caught between self-obsession and the pressing desire of the

masses for ideas and culture that will deal with climate change,

financial crises, terror attacks and the neo-liberal squeeze on the

social welfare system.

These two movements, Romanticism and the Enlightenment, have their

basis in attitudes towards and beliefs in the efficacy of the burgeoning

scientific movement. Romanticism, beginning in the 1770s formed the

basis of an anti-scientific strand in culture over the last two hundred

years while the Enlightenment formed the basis of a scientific strand

roughly between between 1715 and 1789. Both strands have been in

opposition ever since, their ideas reflected through various cultural

movements which sprang up in different countries and at different times,

some revolutionary and some reactionary.

Let’s take a look at these two opposing strands in more detail.

The Anti-Scientific Strand

Romanticism

One of the most important movements is Romanticism particularly as it

still has a strong anti-science influence today. Romanticism was

characterized by its emphasis on emotion and individualism and glorified

the past and nature, putting emphasis on the medieval rather than the

classical traditions of ideals of harmony, symmetry, and order. The

Romantics rejected the norms of the Age of Enlightenment and the

scientific rationalization of nature which were important aspects of

modernity. Isaiah Berlin believed that the Romantics opposed classic

traditions of rationality and it basis in moral absolutes and agreed

values which

led “to something like the melting away of the very notion of objective truth”.

Objective truth and reason were elevated by the artists and

philosophers of the Enlightenment to understand the universe and solve

the pressing problems of the world. However, Romanticism promoted the

individual imagination as a critical authority allowed of freedom from

classical notions of form in art (harmony, symmetry, and order).

Romantics were distrustful of the human world, and tended to strive for a

close connection with nature to escape elements of modernity such as

urbanisation, industrialisation and population growth and therefore

allowed them to avoid questions centred around the working class, such

as alienation, the ownership of the means of production, living

conditions and conditions of employment. The Romantics pursued the idea

of “l’art pour l’art” (art for art’s sake) believing that art did not

need moral justification and could be morally neutral.

According to

Arnold Hauser in

The Social History of Art:

“Revolutionary France quite ingeniously enlists the

services of art to assist her in this struggle; the nineteenth century

is the first to conceive the idea of “l’art pour l’art” [ital] which

forbids such a practice. The principle of “pure”, absolutely “useless”

art first results from the opposition of the romantic movement to the

revolutionary period as a whole, and the demand that the artists should

be passive derives from the ruling class’s fear of losing its influence

on art.” [1]

This position originated with the elites in the nineteenth century

and serves the same function, Romanticism being the main influence of

culture today.

Modernism

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Modernist movement

was generally referred to as the “avant-garde” until the the word

“Modernism” became more popular. Modernism was the rejection of

tradition, and the creation of new forms using reprise, incorporation,

rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody. The Modernist

‘rejection of tradition’, like with Romanticism, is the rejection of

classical notions of form in art (harmony, symmetry, and order).

Modernism (like Romanticism) also rejected the certainty of

Enlightenment thinking. Modernism emphasised form over political

content and rejected the ideology of Realism and Enlightenment thinking

on liberty and progress.

The Realist movement began in the mid-19th century as a reaction to

Romanticism, and Modernism was a revolt against the ‘traditional’ values

of Realism. Realist painters used common laborers, and ordinary people

in ordinary surroundings engaged in real activities as subjects for

their works. However, Modernism rejected traditional forms which over

time became less and less ´real´ and more abstract and conceptualised.

The Great War brought about more disillusionment with Enlightenment

ideals of progress among the Modernists who turned inwards and attacked

art forms, instead of war-mongering capitalism. The Romantic continuity

in Modernism produced individual, horrified reactions but were

ultimately no threat to the ruling elites. Like an angry child smashing

his own toys, the Modernist attacked his particular cultural forms and

then expected the public to pick up the pieces. What was left was

atonalism and abandonment of traditional rhythmic strictures in music,

the departure from traditional realist styles in art and the

prioritisation of the individual and the interior mind and abandonment

of the fixed point of view in literature. The Dada movement, for

example, was developed in reaction to the Great War by ‘avant-garde’

artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern

capitalist society but then only to respond with nonsense and

irrationality in their art works.

As for the Great War, the avant-garde and Modernism – like the

Romantic movement and the French Revolution – failed the masses again as

it stood outside the people’s movement, turning in on itself and

attacking reason instead of uniting with the progressive forces against

war. In the end it was mainly the political movements of

James Connolly in Ireland and

V.I. Lenin in Russia (the two geographical ends of Europe) who organised the working classes against the war and destruction.

David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974), the

revolutionary artist and founder of the Mexican Mural Movement, had this

to say about the Modernist ‘avant-garde’:

“If we look closely at their work it is the most

reactionary movement in the history of culture. It has not developed

anything new in composition or perspective and has lost much of that

which has been accumulated over twenty centuries. It is based on the

hysteria of novelty for the sake of novelty, in order to satisfy a

parasitic plutocracy. The artist who changes his style every 24 hours is

the best-known artist. When he has exhausted all the solutions, the

others become his followers and sink into repetitious imitation.” [2]

The allusion here presumably to

Picasso (1881–1973), famous for changing his style many times, is interesting in relation to

Joaquín Sorolla

(1863–1923) the great Spanish artist whose depictions of ordinary

Spanish people in monumental works of social and historical themes was

overshadowed by Picasso until relatively recently. Cubism, credited to

Picasso as its inventor, was an art style that conflicted with the

representational system in art that had prevailed since the Renaissance,

as the subject was depicted from differing viewpoints at the same time

within the same painting.

Many pseudo-scientific explanations were given to explain Cubism

regarding art in modern society, new scientific developments etc but

even Picasso himself

ridiculed this:

“Mathematics, trigonometry, chemistry, psychoanalysis,

music and whatnot, have been related to cubism to give it an easier

interpretation. All this has been pure literature, not to say nonsense,

which brought bad results, blinding people with theories”. [2]

Indeed, Cubism is probable the most parodied of all forms of Modernist art.

Other Modernist forms such as Expressionism have been seen to be at least critical of capitalism and war, but according to

Lotte H. Eisner who

quotes a ‘fervent theorist of this style’,

Kasimir Edschmid:

“The Expressionist does not see, he has ‘visions’.

According to Edschmid. “the chain of facts: factories, houses, illness,

prostitutes, screams, hunger’ does not exist; only the interior vision

they provoke exists.” [p10]

Therefore, the external reality of life and death for the working class is ignored for the ecstasy of ‘interior visions’.

For Eisner, writing in The Haunted Screen, German Expressionist cinema is a visual manifestation of Romantic ideals. She

writes:

“Poverty and constant insecurity help to explain the

enthusiasm with which German artists embraced this movement

[Expressionism] which, as early as 1910, had tended to sweep aside all

the principles which had formed the basis of art until then.” [pp9-10]

Richard Murphy also notes:

“one of the central means by which expressionism

identifies itself as an avant-garde movement, and by which it marks its

distance to traditions and the cultural institution as a whole is

through its relationship to realism and the dominant conventions of

representation.” [3]

Expressionists rejected the ideology of realism, and Expressionist

art, in common with Romanticism, reacted to the dehumanizing effect of

industrialization and the growth of cities with extreme individualism

and emotionalism, not collective social empathy and political change.

After the Great War and the Russian Revolution, in the 1920s and

1930s, the idea of depicting ordinary people in art spread to many

countries in Realist and Social Realist forms especially as a reaction

to the exaggerated ego encouraged by Romanticism. In the United States

the Ashcan School was well know for for works portraying scenes of daily

life in New York city’s poorer neighborhoods. However, the unsettling

depictions of the darker side of capitalism by the Ashcan School was

soon displaced with Modernism in the Armory Show of 1913 and the opening

of more galleries in the 1910s that promoted the Modernist artwork of

Cubists, Fauves, and Expressionists.

This takeover by Modernism in New York continued into the 1940s and

1950s with the development of Abstract Expressionism, an art form which

was soon promoted globally as a counterweight to the Socialist Realism

style developed in the Soviet Union, especially during the Cod War. The

loose, splashing and dripping of paint in the work of Jackson Pollack

became used as a symbol of the ideology of freedom and free enterprise

in the United States. The victory of Modernism in the United States

served two purposes: national and international. It dampened down the

critical dissent of the Ashcan School while at the same time serving as a

useful tool of foreign policy.

According to

Frances Stonor Saunders in

The Cultural

Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, Abstract

Expressionism was “Non-figurative and politically silent, it was the

very antithesis to socialist realism. It was precisely the kind of art

the Soviets loved to hate.” [4] This was Modernism at its zenith as the

wealthiest of art investors and the most influential art critics

promoted Abstract Expressionism as “independent, self-reliant, a true

expression of the national will, spirit and character.”[5] However, the

size of the confidence trick being perpetrated on the unsuspecting

public became unsettling. According to Saunders:

“It was this very stylistic conformity, prescribed by

MoMA and the broader social contract of which it was a part, that

brought Abstract Expressionism to the verge of kitsch. ‘It was like the

emperor’s clothes,’ said Jason Epstein. ‘You parade it down the street

and you say, “This is great art,” and the people along the parade route

will agree with you. Who’s going to stand up to Clem Greenberg and later

to the Rockefellers who were buying it for their bank lobbies and say,

“This stuff is terrible”?” [6]

The imposition of Modern Art on the public was also noted by the journalist,

Tom Wolfe, who wrote about the 1960s and 1970s art scene in New York in

The Painted Word:

“The notion that the public accepts or rejects anything

in Modern Art, the notion that the public scorns, ignores, fails to

comprehend, allows to wither, crushes the spirit of, or commits any

other crime against Art or any individual artist is merely a romantic

fiction, a bittersweet Trilby sentiment. The game is completed and the

trophies distributed long before the public knows what has happened. […]

We can now also begin to see that Modern Art enjoyed all the glories of

the Consummation stage after the First World War not because it was

“finally understood” or “finally appreciated” but rather because a few

fashionable people discovered their own uses for it.” [7]

It was also in the early 1970s that the Irish artist Seán Keating

(1889–1977), a Realist painter who painted images of the Irish War of

Independence, the early industrialization of Ireland and many portraits

of the people of the Aran Islands, was brought face to face with

Modernism. In a well-known televised interview, Keating, now in his 60s,

was brought around the ROSC’71 exhibition and asked to give his opinion

on the exhibits. As

Eimear O’Connor writes:

“When confronted by The Table, made by German artist Eva

Aeppli (b.1925), Keating said it was ‘downright horrible perversity,

nightmare stuff … an old lady who had gone completely mad and is

dangerous … I think it is morose … vengeful against the human race…'”

[8]

This baiting of a famous Irish humanist whose love of the Irish

people and progress displayed the new confidence of the Irish elites who

had jumped on the Modernist bandwagon as an symbol of fashionability

and of final acceptance by the European elites who would allow Ireland

to join the EEC (EU) in 1973.

Economic Pressure by Seán Keating (1949)

Scene of man bidding farewell to his family as he prepares to emigrate from Aran Islands.

(The Irish peasant betrayed: elevated as a national symbol before Independence yet ignored afterwards.)

Postmodernism

In the meantime, Postmodernism was gaining strength. Some features of

Postmodernism in general can be found as early as the 1940s but it

would compete with Modernism in the late 1950s and became predominant by

the 1960s.

Postmodernism is defined as

follows:

“Postmodernism, also spelled post-modernism, in Western

philosophy, a late 20th-century movement characterized by broad

skepticism, subjectivism, or relativism; a general suspicion of reason;

and an acute sensitivity to the role of ideology in asserting and

maintaining political and economic power. Postmodernism as a

philosophical movement is largely a reaction against the philosophical

assumptions and values of the modern period of Western (specifically

European) history—i.e., the period from about the time of the scientific

revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries to the mid-20th century.

Indeed, many of the doctrines characteristically associated with

postmodernism can fairly be described as the straightforward denial of

general philosophical viewpoints that were taken for granted during the

18th-century Enlightenment, though they were not unique to that period.”

In other words, Postmodernism had a direct line of descent from

Modernism and Romanticism before that. The same Romantic characteristics

show up again – the suspicion of reason, subjectivism and denial of the

ideas of the Enlightenment. Once again cynicism towards the idea of

progress and working class improvement is the mainstay. Every technique

and trick of avoidance of the important issues facing the people’s

movement is used in

Postmodernism:

“common targets of postmodern critique include universalist notions of

objective reality, morality, truth, human nature, reason, language, and

social progress” and “postmodern thought is broadly characterized by

tendencies to self-referentiality, epistemological and moral relativism,

pluralism, subjectivism, and irreverence.”

Postmodernist artists decided that past styles (once criticised for

being ‘traditional’) were now usable in a parodic way along with

appropriation and popular culture. The Postmodernist critique of

universalist ideas of objective reality and social progress, or the

Grand Narratives, has particular implications for the working classes

and popular political movements as their liberatory philosophy and

ideologies are based on them – whatever their supposed successes or

failures in the past. To take them away is to fall back on the

neo-liberal philosophy of the end-of-history and more of the same

globalised capitalism ad infinitum. After the attack on Form in

Modernism, we now get an assault on Content in Postmodernism.

When applied to the people’s movement itself, such as the French

Revolution, Postmodernist historiography for example, all but wipes out

its historic relevance and importance. As

Richard J Evans

writes in

In Defence of History, Simon Schama’s book

Citizens: A

Chronicle of the French Revolution over-emphasises the bloody and

violent nature of the revolution as if the politically-conscious people

taking their lives into their own hands were irrational beings exploding

with an animal lust for violence. Evans comments:

“In Citizens, indeed, the French Revolution of 1789-94

becomes almost meaningless in the larger sense, and is reduced to a kind

of theatre of the absurd; the social and economic misery of the masses,

an essential driving force behind their involvement in the

revolutionary events, is barely mentioned; and the lasting significance

of the Revolution’s many political theories and doctrines for modern

European and world history more or less disappears.” [9]

The more opaque forms of relativistic Postmodernist writing and

thinking were exposed when Alan Sokal refused to get into line and

exposed the French Postmodernists in a hoax essay published in

Social

Text in 1996. According to

Francis Wheen in

How Mumbo Jumbo Conquered the World:

“As a socialist who had taught in Nicaragua after the

Sandinista revolution, he [Sokal] felt doubly indignant that much of the

new mystificatory folly emanated from the self-proclaimed left. For two

centuries, progressives had championed science against obscurantism.

The sudden lurch of academic humanists and social scientists towards

epistemic relativism not only betrayed this heritage but jeopardised

‘the already fragile prospects for a progressive social critique’, since

it was impossible to combat bogus ideas if all notions of truth and

falsity ceased to have any validity.” [10]

The obvious contradictions and cul-de-sacs of Postmodernism

eventually brought it into decline and soon doors opened for a new

obfuscatory philosophy to buttress increasingly crisis-ridden globalised

capitalism – Metamodernism.

Metamodernism

According to

Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker in ‘Notes on

Metamodernism‘:

“The postmodern years of plenty, pastiche, and parataxis

are over. In fact, if we are to believe the many academics, critics, and

pundits whose books and essays describe the decline and demise of the

postmodern, they have been over for quite a while now. But if these

commentators agree the postmodern condition has been abandoned, they

appear less in accord as to what to make of the state it has been

abandoned for. In this essay, we will outline the contours of this

discourse by looking at recent developments in architecture, art, and

film. We will call this discourse, oscillating between a modern

enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, metamodernism. We argue that the

metamodern is most clearly, yet not exclusively, expressed by the

neoromantic turn of late”.

So there you have it – this is the best that Metamodernism can offer –

a return to Romanticism! We have now come full circle as “the

metamodern is most clearly, yet not exclusively, expressed by the

neoromantic turn of late”.

And where is this pressure coming from, to allow a little reality back into the

arts?

“Some argue the postmodern has been put to an abrupt end

by material events like climate change, financial crises, terror

attacks, and digital revolutions […] have necessitated a reform of the

economic system (“un nouveau monde, un nouveau capitalisme”, but also

the transition from a white collar to a green collar economy)”.

So the contemporary crises of capitalism and climate change are

finally impinging on the disintegrating Postmodern artistic

consciousness and the answer is reformism and ‘new capitalism’. However,

Metamodernism

is “Like a donkey it chases a carrot that it never manages to eat

because the carrot is always just beyond its reach. But precisely

because it never manages to eat the carrot, it never ends its chase”.

With a little bit of progressive critique, the Metamodern artist can

regain credibility without ever really challenging the status quo.

From all of the above we can see the common threads tying

Romanticism, Modernism, Postmodernism and Metamodernism together:

individualism, art for art’s sake, suspicion of reason, subjectivism and

denial of the ideas of the Enlightenment. All individualist movements

that oppose the idea of collectivist ideology and action. Movements that

ultimately serve the status quo and the ruling elites. Yet some of

these same elites were involved in the development of the concepts of

the Enlightenment in the beginning. What happened to them?

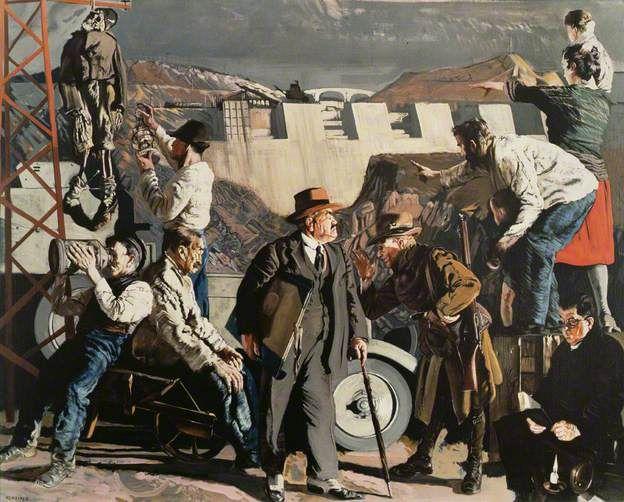

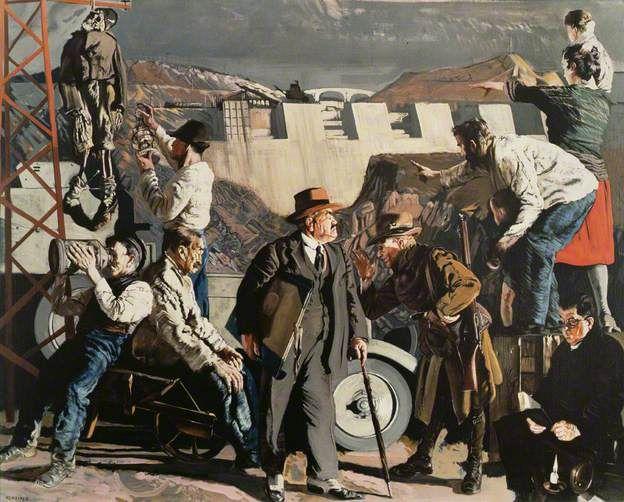

Night’s Candles Are Burnt Out by Seán Keating (1927-28)

Ardnacrusha – Ireland’s first

power-station built by Siemens post-independence in the 1920s, a

hydro-electric dam built on the river Shannon, north of Limerick.

(Disillusioned Irish workers unemployed and drinking as the new elites begin the process of state-building.)

The Scientific Strand

The Enlightenment

The Enlightenment was an intellectual and philosophical movement that

dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 18th century.

Enlightenment thinkers believed in the importance of rationality and

science. They believed that the natural world and even human behavior

could be explained scientifically. They felt that they could use the

scientific method to improve human society. For the artists and

philosophers of the Enlightenment, the ideal life was one governed by

reason. Artists and poets strove for ideals of harmony, symmetry, and

order, valuing meticulous craftsmanship and the classical tradition.

Among philosophers, truth was discovered by a combination of reason and

empirical research.

In the field of political philosophy the English philosopher

Thomas Hobbes

developed some of the fundamentals of European liberal thought: the

right of the individual, the natural equality of all men and the idea

that legitimate political power must be “representative” and based on

the consent of the people. Therefore the Enlightenment popularised the

idea that with the use of reason and logic social development and

progress would be the norm for the masses and science and technology

would be the instruments of human progress. The ideas of the

Enlightenment paved the way for the political revolutions of the 18th

and 19th centuries as it undermined the authority of the monarchy and

the Church. The French Revolution become the first main conflict between

the men of the Enlightenment and the aristocracy. Within the arts this

conflict arose between those who believed that art had a role to play

and those who believed in art-for art’s-sake. As Hauser notes:

“It is only with the Revolution that art becomes a

confession of political faith, and it is now emphasized for the first

time that it has to be no “mere ornament on the social structure,” but

“a part of its foundations.” It is now declared that art must not be an

idle pastime, a mere tickling of the nerves, a privilege of the rich and

the leisured, but it must teach and improve, spur on to action and set

an example. It must be pure, true, inspired and inspiring, contribute to

the happiness of the general public and become the possession of the

whole nation.” [11]

However, the rising bourgeoisie who advocated the ideas of the

Enlightenment realised that their objectives and those of the

revolutionary public were not the same:

“Yet as soon as the bourgeoisie had achieved its aims, it

left its former comrades in arms in the lurch and wanted to enjoy the

fruits of the common victory alone. […] Hardly had the Revolution ended,

than a boundless disillusion seized men’s souls and not a trace

remained of the optimistic philosophy of the enlightenment.” [12]

Thus began the conflict between the new rulers, the bourgeoisie, who

wanted to set limits on progress, and the interests of the toiling

masses who had not yet achieved one of the most basic concepts of

Enlightenment philosophy: the natural equality of all men. This struggle

for political and social freedom took different forms over the next

century or so but had as one of its bases the idea that the arts would

play a role.

Realism

As the bourgeoisie stepped up its development of capitalist society

building factories and markets, the Realist movement reacted to

Romanticist escapism in favor of depictions of ‘real’ life, emphasizing

the mundane, ugly and sordid. The Realist artists used common laborers

and ordinary people in their normal work environments as the main

subjects for their paintings. Its chief exponents were

Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet, Honoré Daumier, and

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.

Courbet hated the aristocracy and royalty, and advocated political and

social change. He painted ordinary people and in sizes usually reserved

for gods and heroes. Realist movements, like the Peredvizhniki or

Wanderers group in Russia, developed in many other Western countries.

Social Realism

Meanwhile, as the the Industrial Revolution grew in Britain, concern

for the factory workers led to a meeting betwen Marx and Engels and a

major change in the ideology of the working class organisations seeking

better conditions. While the Romantics believed that the Industrial

Revolution and its exploitative extremes in the factories was the result

of science, the Marxists instead questioned the ownership of the

factories and who benefited from the greatly increased power of the new

means of production, means that could benefit society as a whole.

Therefore while the Romantics looked back to the medieval artisans and

peasants, the Marxists saw science creating new possibilities for a

better future for everybody.

Social Realism grew out of these changes as Social Realist artists

drew attention to the everyday conditions of the working class and the

poor and criticised the social structures which maintained these

conditions. The Mexican and Russian revolutions gave a fillip to the

Social Realist movement which reached its height of popularity during

the 1920s and 1930s when capitalism was under severe pressure from the

global economic depression. The Ashcan School in the USA and the Mexican

muralist movement were two groups who exerted a huge influence at the

time and many of the artists involved at the time were supporters of

political working class movements. While contemporary Social Realism has

been kept in the background it is still a popular style with

progressive artists.

Socialist Realism

As nationalist struggles of the nineteenth century changed into

socialist struggles during the twentieth century, the style and form of

the art changed too as ordinary people were now depicted as subjects

with dignity and power. This style became known as Socialist Realism. It

was pronounced state policy at the Soviet Writers’ Congress in 1934 in

the Soviet Union and became a dominant style in other socialist

countries. Like Social Realism, Socialist Realism also met with fierce

denunciations and controversy. However, despite its caricature as a

style that depicts people as naïve, happy, joyous ciphers, its

originators condemned any attempt to portray people living in an idyllic

paradise as the work of shallow artists who would never be taken

seriously by the

populace:

“An artist who tried to represent the birth of socialism

as an idyll, who tried to represent the socialist system, which is being

born in hard-fought battles, as a paradise populated by ideal people –

such an artist would not be a realist, would not be able to convince

anyone by his works. The artist should show how socialism is built out

of the bricks of the past, out of the material which the past has left

us, out of the material which we ourselves create in the sweat of our

brow, in the blood of our toil and struggle, in, the hard battles of

classes and in the hard toil of man to remold himself.”

Socialist Realism went into decline in the 1960s as the Soviet Union

itself went from crisis to crisis until its end in 1991. Today it is a

style which is still much criticised. Why is Socialist Realism such a

taboo? Because Socialist Realism is a quadruple whammy – it contains

four elements that elites don’t like:

- Anything to do with the Soviet Union (then) or Russia (today)

- Any depictions of the working class anywhere (which are not subservient)

- Any discussion of socialism or socialist ideology (past, present or future)

- Any realist depiction of opposition to capitalism (that could influence others)

If one looks at ‘history of Western art’ books it becomes apparent

that there are very few positive images of the working class but plenty

of images glorifying monarchs, aristocrats, the middle classes and Noble

Peasants (the useful idiots of nationalism). Representations of

peasants usually take the form of non-threatening genre paintings and

any Socialist Realist art is excluded.

Irish Industrial Development (oil on wood panels) by Seán Keating (1961)

International Labour Offices (ILO) Geneva, Switzerland

(Positive images of Irish workers by Irish artist in Geneva – must be Socialist Realism!)

Conclusion

The fact is that Romanticism in its different forms has made sure to

keep the working classes out of the picture and the only response of the

peoples' movements should be to keep Romanticist influences at arms

length. Romanticism has become the capitalist art par excellence.

Romanticism vacillates between cultures of despair and Nihilism. It is

opposed to logic and reason and its extreme individualism ensures a

divisive affect on any collectivist organisation. Romanticism pervades

most mass culture today and sells egoism and impotence back to the very

people who turn to it for solace from desperation.

The long conflict between Romanticism and Enlightenment ideas

contained in art movements over the last two centuries is set to

continue as new responses to the contemporary crises of capitalism try

to ameliorate the situation or fundamentally change the system

underpinning it. What is needed are new national debates on the role and

function of art in maintaining or changing the structure of society.

Debates similar to those described by an eyewitness to the Paris

Commune, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, who wrote: “a whole population is

discussing serious matters, and for the first time workers can be heard

exchanging their views on problems which up until now have been broached

only by philosophers.” [13]

*

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork

consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well

as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing

based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of

Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed

country by country at http://gaelart.blogspot.ie/. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization.

Notes:

[1] Arnold Hauser, The Social History of Art, Vol 3 (Vintage Books, 1958) p147

[2] D. Anthony White, Siqueiros: Biography of a Revolutionary Artist (Booksurge.com, 2008) p413

[3] Richard Murphy, Theorizing the

Avant-Garde: Modernism, Expressionism, and the Problem of Postmodernity

(Cambridge, Cambridge University Press,1999) p43

[4] Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (The New Press, 1999) p254

[5] Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (The New Press, 1999) p254

[6] Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (The New Press, 1999) p275

[7] Tom Wolfe, The Painted Word (Bantam Books, 1987) p26/7

[8] Eimear O’Connor and Virginia Teehan, Sean Keating: In Focus (Hunt Museum, 2009) p33

[9] Richard J. Evans, In Defence of History (Granta Books, 2000) p245

[10] Francis Wheen, How Mumbo Jumbo Conquered the World (Harper Perennial, 2004) p89/90

[11] Arnold Hauser, The Social History of Art, Vol 3 (Vintage Books, 1958) p147

[12] Arnold Hauser, The Social History of Art, Vol 3 (Vintage Books, 1958) p157

[13] Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, in Le

Tribun du Peuple, May 10, 1871, quoted in Stewart Edwards, The Paris

Commune 1871 (Quadrangle, 1977) p283